Yingiya Mark Guyula maiden speech - NT parliament 2016

"We talk about closing the gap, but what gap are we talking about? The people of my electorate understand that this gap is the gap created when Yolŋu law is not properly acknowledged ...

That gap grows when Yolŋu children are forced into English-only schools, taught in a language they do not speak or hear in their community, like sending a Balanda child to a Yolŋu language-only school in Darwin.

The gap grows when Yolŋu children on homelands do not have equal access to education, qualified teachers attending every day and working with Yolŋu teachers and community to develop bilingual, bicultural curriculum, and for the children that is created on country and taught through Yolŋu language and culture, discipline, rehabilitation, educating young men and women towards being responsible, respectful parents and future leaders."- Yingiya Mark Guyula, extract from maiden speech

Northern Territory Parliament 2016

Independent Member of Nhulunbuy, Yingiya Mark Guyula, reading his maiden speech. Northern Territory Parliament 2016

(Image: Northern Territory Government via ABC News)

The Thirteenth Assembly convened on 18 October 2016

Uncorrected Proof - (Closest translation/pronunciation of Yolŋu = Yolngu ) anscii 331

Yolŋu Languages

Yingiya Mark Guyula (Nhulunbuy): (member spoke in language).

Translation: I am here from the Liya-dhalinymirr Djambarrpuyungu people of East Arnhem Land. I am Liya-dhalinymirr Djambarrpuyungu leader. I stand before this parliament here in good governance and respect.

Firstly I would like to acknowledge the land that I am standing on and the Larrakia Nation’s people and their ancestors past and present.

Let me begin by saying this is not something that I wanted to do. I did not want to become a politician but we Yolŋu have tried many ways of gaining recognition of Yolŋu law, and none have worked. I am here as an elected member but also as a diplomat from the Yolŋu (inaudible) bringing two parliaments together.

Our 1998 petition to Prime Minister John Howard read like this:

We request that the Australian government recognise

-

the Dhulkmu-mulka Bathi (Title Deeds) which establish legal tenure for each of our traditional clan estates.

Your Westminster system calls this native title.

-

the jurisdiction of our Njarra’/Traditional Parliament in the same way as we recognise your Parliament and Westminster system of government

- both formally and legally recognise our Madayin system of law.

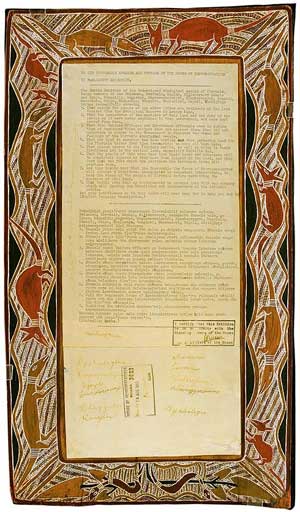

![]() Bark Petition Transcript 1963 pdf

Bark Petition Transcript 1963 pdf

![]() Barunga Statement Transcript 1988 pdf

Barunga Statement Transcript 1988 pdf

![]() Petition to Kevin Rudd Transcript 2008 pdf

Petition to Kevin Rudd Transcript 2008 pdf

Similar requests for rights, land ownership and our way of life and self-governance were also made in the 1963 bark petitions, the 1998 Barunga statement and the 2008 petition to Kevin Rudd.

The leadership of Yolŋu people has always been very public about its request for treaty.

On numerous occasions this has been done by statements and petitions to the Australian government.

Perhaps our people’s most well-known declaration for treaty is the song by Yothu Yindi called Treaty.

Today I bring a letter stick to be tabled in the parliament; this is brought on behalf of the Yolŋu nation’s assembly.

The subsequent message is one of the Yolŋu nation’s, outlining the equal standing of the Njarra’ institution compared with Australian parliaments.

It is therefore a declaration of ongoing Yolŋu sovereignty while being a diplomatic gesture of intent and also the invitation to work towards a place of mutual acceptance between Yolŋu and Australian jurisdictions.

The declaration reads like this:

We declare that we have not been conquered. We declare that to this day we are a sovereign people. We declare that we will subject to our Madayin system of law constituted by the unseen creator of the universe and reveal to givers of law (inaudible), and we continue to steward this system through our lawful authroities and governments.

Our Madayin system of law is guarded by the Yothu Yindi separation of powers. Our Madayin system of law is a rule of law not a rule of man. Our Madayin system of law is the equal of any other system of law.

This is the most important thing I will say today; it is the reason I am here. It is the reason I stand before you.

To give you an even greater understanding of why I am here, standing before you, I will tell you about myself. I was born and raised in the bush. My father did not depend on others. He was given a job at the mission in Galiwinku, using the traditional knowledge. He used the skills he learnt from his father as a crocodile hunter, and this is what I learnt in my younger days until I was 10. I stayed away from school; I was camping, hunting, fishing and crocodile hunting with my father, and collecting bush foods with my mother.

At 10 years old I made the decision to go to school. I could not read or write and was laughed at. I was put in a class with younger children and quickly picked up skills. In one year I was put three levels beyond the class where I first started, where children laughed at me. Most of those kids finished school in primary school. I went to Dhupuma College and then Nhulunbuy High School.

I believe that my learning on country until the age of 10 gave me a strong Yolŋu identity, confidence and the ability to succeed later in life. Growing up on my mother’s parents’ country and my father’s country, I was nurtured—where my ancestors know me, where I feel strong standing on my country. Later I took up a job with Mission Aviation Fellowship in Nhulunbuy and Galiwinku as an aircraft maintenance engineer. They had a flying school in Ballarat, Victoria and I got my unrestricted private pilot’s licence to fly all over Australia.

I was learning about Balanda and getting a mixture of culture. I wanted to be on country for ceremonies and the traditional education, but I was also starting to enjoy a Balanda lifestyle. I was like a dog chasing two masters. I was picking up Balanda habits and then I had to drop that a catch up with my own culture. This is a hard time for many caught in two worlds. People say, ‘Come to the mainstream’ and on the other hand, ‘You need to be a leader and lean song lines and ceremonies which work towards those thing that are the law’.

I am now at the end of my full education with Yolŋu knowledge. There is still a lot to learn but I am a Djirrikaymirr. This is a leadership title of those who have a high level of learning. I have the authority to make constitutional decisions, create and produce a law. I have established this knowledge since my early 20s. Over the past 35 years I have dedicated myself to learning Yolŋu law which has provided everything we needed for thousands of years.

The issue of Yolŋu law is the main reason I have been selected by my electorate to represent them in the Northern Territory parliament. I am very proud of all grassroots support—Yolŋu and Balanda together— that circled around this campaign.

I return to my story of a dog and two masters. This is two masters going in different directions – one going this way and one going the other way. We talk about closing the gap, but what gap are we talking about? The people of my electorate understand that this gap is the gap created when Yolŋu law is not properly acknowledged. When the power of self-determination is increasingly being removed, that gap grows. When our people are starved out from the homelands and forced into major growth hub towns by the funding our infrastructure, health facilities, roads, homeland schools, etcetera.

Homeland centres are not hunting and fishing camps, but are residential clan states. They are centres of our society, foundational places of our social contract given importance by tradition and law at the foundation of our world. That gap grows when Yolŋu children are forced into English-only schools, taught in a language they do not speak or hear in their community, like sending a Balanda child to a Yolŋu language-only school in Darwin.

I understand this pressure. Even as an adult learning to fly I have failed written exams several times, but I was always above average in practical exams. I could navigate Victorian country almost instantly. We are capable of learning both ways but we need the strength of our first culture and language to obtain both.

The gap grows when Yolŋu children on homelands do not have equal access to education, qualified teachers attending every day and working with Yolŋu teachers and community to develop bilingual, bi-cultural curriculum, and for the children that is created on country and taught through Yolŋu language and culture, discipline, rehabilitation, educating young men and women towards being responsible, respectful parents and future leaders.

The gap grows when there is no training on country for young men and women who have finished their high school education to learn skills to gain employment that will allow them to be a part of their community. The gap growers outside the controls of economy ignore our corporate entities and limit our rates to negotiate terms of trade and benefit from our resources. The gap growers.

Family violence is happening now because young men and women have not been through a traditional process of learning to be responsible and preparing for respectful relationships. Our rights to maintain justice has been revoked by Balanda institutions. The only way to fix this is with policies of self-determination, self-management, self-governance and ultimately, a treaty.

This is not the first treaty for Yolŋu people. When the Macassans first landed on the north-east coast of Arnhem Land they recognised Yolŋu sovereignty and that a system of government already existed here. The Macassans negotiated for the right to fish certain waters and with our authority they were granted this right. In exchange for this fishery agreement, payments of clothes, tobacco, metal axes, knives and rice were made. Yolŋu of Arnhem Land also traded turtle shell, pearls and cypress vines, and some of our people were employed as trepangers.

The relationship between the Macassans and the Yolŋu tribes became so intertwined that the Macassan culture became included in some of our songlines and law. Songlines of tobacco and alcohol. Stories like the great whale hunter Wuymu, the Wurramala hunter, and culture like the use of flags.

We had two international treaties with the Macassans of Sulawesi. They engaged us with respect and honour, and they became our kin.

When I ask for a treaty, I am thinking of three requirements: the recognition of the Malayan system of law; the recognition of the East Arnhem Land body of government; and compensation for lost revenue from the blockage of historical international trade with the Macassans. This is called buyada, meaning restitution for wrongs done.

There is a going to be disagreement due to differences in cultures, but this will help us. It is like a footpath that has become overgrown or blocked. We need to trim the trees and the pathway again. This will hurt, but it will draw attention to areas that need to be closely examined and questioned.

Only through respectful dialogue and working together can we call Australia a nation based on the principles of democracy. A treaty will empower us, give us self-management, self-determination, bring pride and outcomes, allow us to make decisions for ourselves and put us in charge of our own destiny.

A treaty will allow us to move from the oppression of dependency and have a place where we might be human. I am here as a representative of the seat of Nhulunbuy, and I want to represent everyone; both Yolŋu and Balanda.

I am also here as a clan leader, and I am here as a representative of Yolŋu nations and its system of governance. I ask elected members to be part of the change that my electorate has voted for, in recognising Yolŋu law and walking with us in partnership towards a treaty.

I seek leave to table this letter stick from Yolŋu nations to the parliament.

Leave granted.