Wadjemup (Rottnest Island): the internment camp turned favourite holiday destination, without debate

This prison Island is a place where Aboriginal men were shipped to in chains from as far a the Kimberley region, a few thousand kilometers from their Homelands. One in ten prisoners died of disease, malnourishment or bashed to death by the prison guards. Others were flogged with lead-weighted whips or chained across a raised iron bar for punishment.

Prisoners were lined up in the central courtyard and collapsed in shock when forced to watch five condemned men hanged, their bodies carted to a nearby dump and buried in unmarked graves.

Celeste Liddle The Guardian 15 October 2014

Australians are renowned for their love of travel. But when it comes to Rottnest Island, this comes at the cost of ignoring the violence Aboriginal people have endured and the disrespect of walking on unmarked graves.

It takes a unique country to name a century-long former internment camp as its favourite holiday destination. Such a country would either have to be one with rather macabre fascinations or a genuine interest in acknowledging historical injustices as a way of moving towards a better future. Or it could just be Australia.

In a poll conducted by travel provider Experience Oz, Rottnest Island took the top spot when it came to favourite Australian holiday destinations. It’s not surprising that the natural beauty and unique wildlife were mentioned as to why Rottnest was number one. The hundreds of Aboriginal men buried in unmarked graves probably aren’t an island drawcard for most tourists. If tourists indeed know that this what they’re walking over when exploring the island.

When Aboriginal people speak of our history in this country, these stories are often dismissed. Every Australia Day, this national dismissal of Aboriginal experience is paraded in public for all to see. Aboriginal people are continually accused of focussing only on negatives; of promoting “black armband history” at the cost of celebrating alleged national positives. When it comes to the history of Rottnest though, to try and argue that there are positives to celebrate is impossible.

The proper acknowledgement of the gruesome history of Rottnest has been called for for a very long time. Only two weeks ago, Murdoch University academic and Minang-Wadjari man Glen Stasiuk was quoted calling for the closure of Rottnest Lodge Accommodation and asking that it be turned into a museum and appropriate memorial.

50 Second Announcement - MP3 File (National Indigenous Radio)

Rottnest Lodge claims as part of its lodgings “The Quod” – an octagonal building housing the Aboriginal prison which was in operation from 1838 to 1931. Each luxury hotel room encompasses three of the old cells in which at least seven prisoners were crammed. The Quod grounds where five men were hung on gallows serve as a grassy area for hotel guests to sun themselves and relax. At least 10% of the prisoners there died; of malnutrition, of illnesses, of brutality. Stasiuk believes nine out of 10 people who stay at The Quod don’t know this history.

Certainly, Rottnest Lodge doesn’t go out of its way to advertise it to potential guests either. The Quod rooms are described as being “rich in history”, which I guess is one way to put it. Additionally the Lodge itself is noted as once being the Summer residence for the governor of WA, yet the website neglects to state much else about the other buildings.

Much of what else stands in Rottnest today was built of Aboriginal suffering. Michael Sinclair-Jones describes the island buildings and sea retainer walls that were built from Aboriginal prisoner labour, as well as the former campground which sat on top of what is the largest deaths in custody gravesite in this country. At best it seems this is glossed over with local and governmental arguments consistently being it would cost too much to acknowledge these sites. At worst, it is the denial of violent practices enacted against Aboriginal people to keep others feeling comfortable when visiting such places.

Gerry Georgatos states that the rate of imprisonment in Western Australia of Aboriginal men today is nine times the rate of imprisonment of black men in apartheid South Africa. Perhaps the horrors of Rottnest are not as deeply buried in the past as most would pretend. Certainly though, it is difficult to think of anywhere else in the world where a horrific internment camp has been swept so easily under the national carpet.

Australians are renowned for their love of travel and holidays. When it comes to Rottnest Island though, this travel comes at the cost of ignoring one of the most horrific examples of displacement, violence and death that Aboriginal people in Western Australia have endured. It is well overdue that Rottnest’s history is acknowledged and its victims commemorated. Until then, the best holiday destination in Australia continues to be built upon a lie.

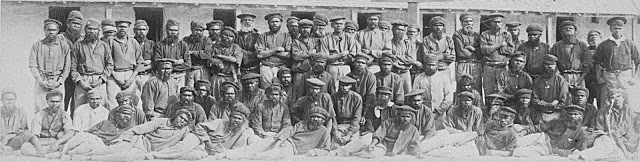

Aboriginal prisoners in The Quod - hundreds died of disease, malnutrition or were beaten to death by guards

1. One in 10 prisoners who slept here died of disease, malnourishment or bashed to death by the prison guards. Others were flogged with lead-weighted whips or chained across a raised iron bar for punishment. Prisoners were lined up in the central courtyard and collapsed in shock when forced to watch five condemned men hanged, their bodies carted to a nearby dump and buried in unmarked graves. 2. Beach holding cell where Aboriginal prisoners started years of brutal captivity, then death. 3. Inside the windowless holding cell. Terrified Aboriginal prisoners were held here after being chained together by the neck and ankle and transported from Fremantle in a treacherous voyage that took up to nine hours in an open longboat.

Gerry Georgatos The Stringer 15 October 2014

Image: Aboriginal prisoners in the courtyard of the Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Prison c1883

(Image; State Library of Western Australia, 6968b)

Friday 17th October, 2014, the First People of the western region of this continent who were imprisoned on Wadjemup, between 1841 to 1903, will be remembered by their descendants. Their ancestors were incarcerated for the crimelessness of refusing to hand over their Country to the colonialist invaders who history often immorally describes as “settlers”. The remembrance is being led by Nyungah Land and Culture worker, Iva Hayward-Jackson. Mr Hayward-Jackson said, “They will not be forgotten.” Mr Hayward-Jackson said that the remembrance will become an annual event.

Wadjemup, known to most as Rottnest Island, one of WA’s best known tourist hotspots, 19km off the Perth coast, was once a penal colony for the First Peoples of what is now called Western Australia. Young boys and men were transported to Wadjemup from all over the western part of this continent by the colonial invaders – many never to return. For the majority, their only ‘crime’ was to refuse to budge from their respective Country, the homelands that they had taken care of all their lives, and who their ancestors going back up to one hundred thousand years ago took care of. One hundred thousand years of relative peaceful living had come to an abrupt end.

Wadjemup is a place where mums and dads take their families to relax and unwind, enjoying the many beaches and pristine waters. The worst that can happen is a child falling off a bike and grazing a knee. However, a brutal colonial history languishes forever over Wadjemup – ‘a place across the waters’ and of ‘spirits across the sea’ according to Noongar/Nyoongah/Nyungah/Nyungar/Bibbelmun lore. On this little island is recorded an unsettling past, the largest number of Aboriginal deaths in custody. The Quod building was built by forced labour, by the Aboriginal prisoners, and it is where they were to be incarcerated and where many of them would die.

The horrific conditions were more than just horrific, they were inhumane – squalid, cramped, dank and dark.

I arrived in Western Australia in 1994, and it now appears WA is where my bones one day may well be laid to rest. A couple months after making WA my new home I was invited for a week to Rottnest Island, not knowing any of its dark history, and I stayed at the Quod.

Within days, I learned of the Quod’s history, piecing together anecdotes and short paragraphs found in the island’s pamphlet literature, and I was jarred by the notion of sleeping where so many of the crimeless First People of this part of the world were let to suffer, to drown in their anguish, where so many died. It didn’t just feel wrong, it was wrong. With the Quod’s history in my contemplations, I couldn’t get to sleep on the third night, seeing imaginary faces around me, imagining the narrative and the questions of those past. I sat outside the Quod for quite some time, while five companions were able to find their sleep. They were sleeping among the dead. I finished up sleeping off that night on a nearby beach, and waking up at the crack of dawn to walk into the crisp pristine waters for a swim and to remember once again unnecessary human suffering, voices long gone hollering from the past.

For the rest of my stay on Wadjemup I would sleep in other swiftly arranged accommodation.

The Quod was built in 1838 and the cells were 3 metres by 1.7, each sleeping seven prisoners. There were no beds, no windows, no toilet buckets. The Quod’s 21 units are actually larger than the prison cells, having been doubled in size to accommodate in relative comfort the needs of holiday makers. There were between 21 to 29 prison cells built over time. It is known that these cells held up to 167 prisoners at any one time.

The Quod building is the site of the most extensive deaths in custody numbers in Australia. The building, for many decades, had been used as accommodation on the Rottnest Island resort, much to the despair of Nyungah Elders and communities. Protests occurred on the island. In 2001 a significant Nyungah led protest captured the attention of media, with many protestors carrying Aboriginal flags walking through and around the grounds of the Quod, and as a result highlighting to many West Australians a dark chapter in the State’s history.

The Quod site is where at least 370 First People died in critically austere dank and dark miserable conditions. Perth historian Neville Green estimates that at least 287 First People died on the island prison but other estimates have it at 370 with others believing it could be up to 700 deaths.

Near one of the island’s most popular swimming areas, the Basin, which is near the tourist hub of the island, the Settlement, lie the bodies of thereabouts one hundred boys and men. Elders from all over the State remain frustrated that Australia’s largest unmarked burial site remains neglected and trodden over by tourists. There is a history of tourists finding skulls and bones.

In 1970, sewerage works to extend the golf course unearthed 12 skeletons in a grove of pine trees, right near the Quod. It was not till 1985 that the Aboriginal Sites Government department recorded the approximate location of the burial ground(s). Following 1988 protests on the island, ground penetrating radar was used by the Government to estimate the extensiveness of the burial grounds. In 1992, the State Aboriginal Authority budgeted $400,000 to contribute to a commemorative centre and memorial right nearby the burial ground. However the project lapsed and never happened.

In 1994, then WA Premier Richard Court acknowledged at a meeting with Nyungah Elders that the island was the site of the largest deaths in custody burial ground but still no memorial eventuated.

Many of the island’s buildings, built by forced labour, now sleep tens of thousands of tourists each year. The buildings built by the sweat and blood of First People are now adored by the tourists and are considered ‘heritage landmarks’. First People built the island’s Government House, which has been converted to Rottnest’s biggest hotel, and they built the Hay Store, which has been converted to the museum, and they built the church, and the Salt Store, and they built the myriad scatter of waterfront cottages that so many tourists have to book months in advance in order to have a chance to secure their accommodation, and they built the Quod, an eight sided prison, which only a few decades after the prison was closed down became the island’s signature piece tourist accommodation.

Prisoners were flogged with lead weighted whips, and were chained across a raised iron bar for punishment. There are many archived accounts of horror, brutality, tragedy, inhumanity – Rottnest was a vacuum of inhumanity. On one occasion, prisoners were lined up in the central courtyard and some collapsed in shock when forced to watch five condemned inmates hanged – their bodies carted to a nearby dump and buried unmarked.

One of the Nyungah people’s senior Elders, Richard Wilkes, said that “the 370 Aboriginal prisoners were quickly buried, most of them wrapped in filthy blankets.”

“They should have been buried facing east to greet the rising sun over the land of their ancestors.”

Except for a few attributions in some of the deaths in various literature, no records were kept about the manner and cause of death of the first 203 Aboriginal prisoners to die on the island.

The island prison’s first superintendent was Henry Vincent, someone who colonial history textbooks have talked up and after whom shires and streets are named after throughout Western Australia, and of whom statues and portraits abound. He was a ruthless and harsh superintendent and according to official records was barely literate, and according to historians and authors was a ‘disciplinarian’. He had served in the Napoleonic Wars and had lost an eye in the Battle of Waterloo.

In 1846, the colony’s Governor John Hutt ordered an inquiry and in testimony provided to the inquiry, British soldier Samuel Mottram alleged under oath the hearsay from overseer Joseph Morris that Superintendent Vincent killed two Aboriginal prisoners and without having it recorded had them buried.

Another soldier, Private John Williams also took the oath and described having seen part of an Aboriginal prisoner’s ear on the ground.

Private Thomas Longworth said he saw Supt Vincent “pull the ear rather severely, and then shaking his fingers, as if to throw something away off his hands, wipe his fingers on his trousers.” He saw the Aboriginal prisoner “with the gristly part of one ear wanting.”

In a documented incident, Government archived, a 60-year-old prisoner, who claimed to be sick and too unwell to move, was bashed twice in the face with a bunch of keys while on his knees pleading that he was not well. After being hit the second time he fell over, and was allegedly kicked. He was found to be unconscious and died later than night in his prison cell. There is controversy as to who struck the prisoner. An autopsy of the prisoner produced an inexplicable ‘finding’ that the man died of ‘lung disease’.

One of the assistant superintendents was Henry Vincent’s son, William. According to accounts from the time, however hearsay, many islanders believe that it was Henry Vincent who hit the prisoner, but William is alleged to have taken the blame to shield his father from scrutiny. Surprisingly, William Vincent was convicted of assault and sentenced to three months hard labour in the police stables. This is the only time there has been a conviction of someone for their hand in an unnatural hand in a death in custody.

WA’s Battye Library records the savage brutality sustained upon the 3,760 First Peoples prisoners between 1841 to 1903. The prisoners were as young as 8 years old and others in their seventies. They were often shackled in heavy iron chains, around their necks and ankles and marched scores of kilometres on the mainland while in transit to Rottnest Island. They came from all parts of Western Australia, and from vastly different Country and cultures to each other, with different languages, dialects and customs.

The Battye Library records, “Prisoners lay cold and wet surrounded by excrement on damp stone floors as deadly influenza raged through their draughty cells.”

“Aboriginal men from as far as the Gascoyne, Fitzroy River and the Kimberley arrived up to twenty at a time, shivering in chains in an open boat, cold, wet and sea sick, clad only in thin blankets.”

“Many suffered pneumonia, scurvy, eczema and dysentery as they lay wet and shivering in threadbare blankets on cold stone floors, constantly damp in winter from being flushed out daily with buckets of cold water to remove overnight faeces and urine. “

The stench from the prison’s open cesspit was so nauseating to Chief Warder Adam Oliver that he complained to an 1884 Government inquiry chaired by Surveyor-General John Forrest, later to be Premier. He complained that ‘offensive air’ was permeating his quarters and ‘ruining the health of his wife and four children.’ But, he described to the ‘inquiry’ that the treatment of prisoners was ‘humane and kind.’

Despite Henry Vincent’s brutality he is remembered kindly by history, and in his time he owned a venerated reputation as a pioneer, and for coordinating the development of many of the buildings on the island.

Perth historian, Neville Green, said that the site should be respected, “It is comparable to transforming Auschwitz concentration camp into holiday cottages.”

At least one in ten of the First Peoples incarcerated and subjected to slave labour on Wadjemup died from disease, malnutrition, maltreatment and abuse. Indeed, the fact remains that at least 370 First People lay in unmarked graves – walked over, camped on, holidayed on. The memorial centre cannot come quick enough, and a history with a full suite of displays needs to be incorporated in such a centre and in the island’s museum.

Celeste Liddle is an Arrernte First Nations woman living in Melbourne. She is the current National Indigenous Organiser for the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU). Celeste blogs personally at Rantings of an Aboriginal Feminist and is particularly interested in education, politics, and the arts

Celeste Liddle is an Arrernte First Nations woman living in Melbourne. She is the current National Indigenous Organiser for the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU). Celeste blogs personally at Rantings of an Aboriginal Feminist and is particularly interested in education, politics, and the arts Gerry Georgatos is a contributing journalist and editor of The Stringer. He is a PhD researcher with academic work in Aboriginal deaths in custody and suicides crises. He also contributes to The National Indigenous Radio Service and The National Indigenous Times.

Gerry Georgatos is a contributing journalist and editor of The Stringer. He is a PhD researcher with academic work in Aboriginal deaths in custody and suicides crises. He also contributes to The National Indigenous Radio Service and The National Indigenous Times.