Governor Macquarie, 'The father of the Stolen Generations' - in 1815

Ms Norman-Hill, is a descendent of one of the first stolen children in 'Australia' said it was difficult to swallow modern-day statistics showing that children from First Nations families are more likely to be taken away from their families."Recent studies show the rate of indigenous children being removed from their families is 10.6 times the rate of non-indigenous children nationally and higher in every jurisdiction," she said. "History and research shows that removing our children from their families is not in their best interest."

In 1815 the children were taken away 'for their own good', to be assimilated under Governor Macquarie. The only things that have changed since then is our people have been pushed further away from their homelands and further marginalised.

(Image: Augustus Earle, National Library of Australia)

Esther Han SMH 22 January 2015 (edited)

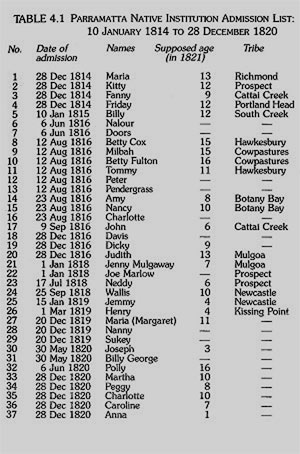

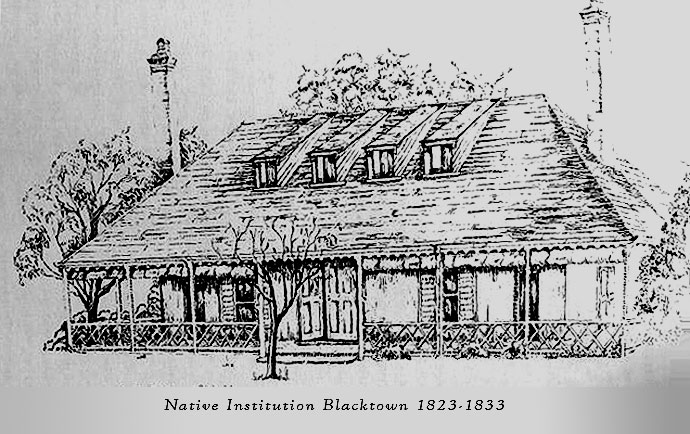

At least 37 Aboriginal children suffered the same trauma of separation before the school's closure in 1823

(Sydney Morning Herald)

Enlarge Image

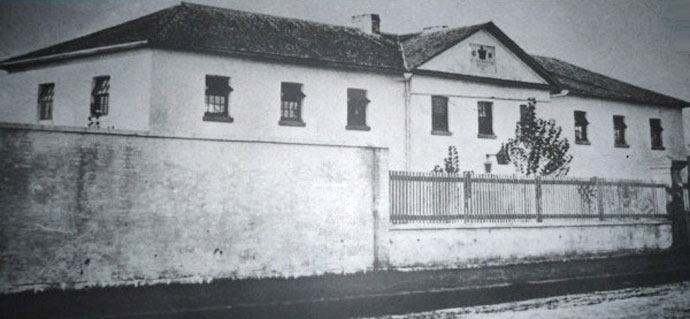

(State Library of NSW)

In January 2015, Rosemary Norman-Hill visited a site of a school where 200 years before then her great-great-great grandmother Kitty was forced to abandon her Aboriginal way of life and integrate into white society.

She said old records showed Kitty was one of the first Aboriginal children to be removed from their parents under forced assimilation orders. Kitty was in the founding group of students at the Parramatta Native Institution, opened by Governor Lachlan Macquarie on 18 January, 1815.

Three weeks earlier, Kitty had been split from her family of the Cannemegal Prospect tribe and forced to live at the school to be "civilised, educated and Christianised" - foreshadowing the policy leading to the Stolen Generations.

220 of the stolen children's descendants gathered for the first time at Parramatta Town Hall to reflect on their shared histories and to begin work on preserving the students' legacy.

"We need to raise awareness to the wider community – both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples – about who these children were, what happened and why as this has largely been forgotten," said Ms Norman-Hill, who organised the 200th anniversary commemoration.

"It is clear from the General Orders that the intention was for these children to lose their language, their culture, their heritage and their Aboriginal way of life."

The children were taught to read and write, learn bible scriptures and arithmetic, according to the scant records available. The girls focused on domestic duties and needlework, while the boys learned about farming and machinery.

But Governor Macquarie's written orders show that no child was allowed to leave – even with their parents and relatives – until they had reached their mid-teens.

Ms Norman-Hill, in the midst of completing a PhD about the institution at Southern Cross University, was shocked by the dearth of documents and lack of knowledge about the school, which was once located next to St John's Church.

"I was mortified that when I spoke to people about it, Aboriginal people, they didn't know about it," she said.

With the support of Parramatta Council, Ms Norman-Hill wants to create a "healing" centre, a place where recorded oral histories, letters, photographs, and art works about the institution can be stored and displayed.

"Our elders are dying, and once they're gone, their knowledge and stories are also gone. So we need our storytelling to be passed on and to survive. Our oral history is critical," she said.

"We want our children to know. We want them to be resilient and build a strong culture. We are a testimony to the fact the Darug people not only survived but are thriving."

Parramatta lord mayor Scott Lloyd attended the commemoration on Sunday. He said he had discussed with community representatives about continuing the memories with art installations, music, theatre and the written word.

"It was a part of history that was nearly forgotten. For a community to learn about another part of our history, which a lot of people didn't even know existed, is important," he said. "It's a great opportunity to learn from the past so we don't repeat any mistakes."

Ms Norman-Hill also said it was difficult to swallow modern-day statistics showing that children from indigenous families are more likely to be taken away from their families.

"Recent studies show the rate of indigenous children being removed from their families is 10.6 times the rate of non-indigenous children nationally and higher in every jurisdiction," she said.

"History and research shows that removing our children from their families is not in their best interest."

(History of Aboriginals Sydney - Link)

(Parramatta Heritage Centre website)

In 1915, in New South Wales, the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 gave the Aborigines' Protection Board authority to remove Aboriginal children "without having to establish in court that they were neglected"; it was alleged by Professor Peter Read that Board members sometimes wrote simply "For being Aboriginal" as the explanation when recording a removal,[1] however the number of files bearing such a comment appear to be on the order of either one or two with two others bearing only the word "Aboriginal".[2] At the time, some members of Parliament objected to the amendment; one member stated it enabled the board to "steal the child away from its parents", and at least two members argued that the amendment would result in children being subjected to unpaid labour tantamount to "slavery".[1]

Moving on 200 years

In 2015 and beyond, government's and their servants remove children at a larger rate than ever before and instead of supporting people who are the victims of ongoing government abuse, poverty and displacement, the peoples themselves are blamed for their inherited circumstances and forcibly remove their children, some people have been/or still are subject to intergenerational forced removals and assimilation indoctrination, thus placing many into further despair. This leaves many individuals in a situation of being alien to their Aboriginal culture, not fitting into the European culture and thus causing a chain-reaction of imprisonment, poverty self-harm and suicide.

Further information:

[1] Bringing Them Home report, part 2, chapter 3.

[2] Read, Peter (18 February 2008). "Don't let facts spoil this historian's campaign".