Expanded doctrine of terra nullius - very much alive in Australia

Ghillar Michael Anderson, 17 September 2014

Expanded doctrine of terra nullius - very much alive in Australia as confirmed in the Queensland Rates Dispute case.

Although Mabo (No.2)supposedly removed terra nullius from the Australian legal system as its basis of sovereignty, the truth is very different. I can summarise the outcome of the Queensland Supreme Court's 'Rates Dispute' case, which clearly relies on an expanded doctrine of terra nullius to deny us justice.

Justice Philippedes in the Supreme Court of Queensland confirmed the difficulty associated with Aboriginal Peoples' ability to gain any kind of justice within the legal system established within the colonies of Australia. The courts now hold themselves as the protectors of the early illegal regimes.”

This is verified in the decision of the Supreme Court of Queensland in the Ngurampaa v Balonne Shire & Anor [2014] QSC 146 known as the Euahlayi Rates Dispute case.

Justice Philippedes in her judgment agreed with Balonne Shire Council's argument that Mabo (No. 2) established that:

At the time of acquisition of Australia sovereignty, international law recognised acquisition of sovereignty not only by contest, cession, and occupation terra nullius, but also by the settlement of inhabited lands whether that process of “settlement” involved negotiations with and or hostilities against the native inhabitants. The High Court recognised this last mentioned method of the acquisition of sovereignty as applicable in the case of sovereignty. [emphasis added]

This position is clearly contrary to the International Court of Justice decision in the Western Sahara Case, which concluded that sovereignty remains with the Peoples. [Western Sahara Advisory Opinion of 16 October 1975]

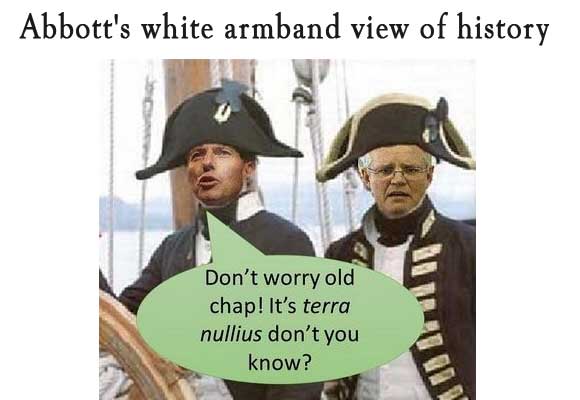

Tony Abbott's dismissive statement on the evening Justice Philippedes delivered her judgment on Euahlayi Rates Dispute case confirms the struggle the Commonwealth of Australia has in establishing any valid sovereignty:

Our country is unimaginable without foreign investment. … I guess our country owes its existence to a form of foreign investment by the British government in the then unsettled or, um, scarcely settled, Great South Land. [4 July 2014 Sydney Morning Herald].

PM Abbott's push to have Aboriginal and Torres strait Islanders 'Recognised' in the colonial Constitution and Pearson's recent statement of 10 September 2014 in The Australian about meeting the government halfway on racial bigotry, further emphasises the legal quandary the Commonwealth of Australia finds itself in.

Ghillar Michael Anderson's statement in full:

Although terra nullius was supposedly removed from the Australian legal system as its basis of sovereignty, the truth is very different. I will summarise the outcome of the Queensland Supreme Court's 'Rates Dispute' case, which clearly relies on an expanded doctrine of terra nullius to deny us justice.

The Supreme Court of Queensland confirmed the difficulty associated with Aboriginal Peoples' ability to gain any kind of justice within the legal system established within the colonies of Australia. The courts now hold themselves as the protectors of the early illegal regimes. This is verified in the decision of the Supreme Court of Queensland in the Ngurampaa v Balonne Shire & Anor [2014] QSC 146 known as the Euahlayi Rates Dispute case.

In setting out the background to the Queensland Rates Dispute case Judge Philippedes confirmed a difficulty that the Local Shires have, or any creditor has, with respect to concluding any satisfactory claims for money owing in relation to those lands. Justice Philippedes set out that:

All transfers of freehold have been and continue to be subject to s 174 of the Land Act 1994 (Qld), such that the property may not be transferred without the approval of the Governor-in-Council.

If we are to accept this conclusion by Justice Philippedes, then the land laws in Queensland create enormous difficulties because on the face of this argument the Queen of England continues to hold all land in Queensland, including freehold; a proposition I am sure many non-Aboriginal landholders would want to know more about, not just Aboriginal people.

Justice Philippedes goes on to look at the 15 January 2014 decision of the St George Magistrates Court [MAG-50022/13] where Magistrate Ryan accepted that there was a question of “whether the Commonwealth properly gained [the] lands from the indigenous inhabitants”, which the Magistrate considered was a question to be dealt with by the Native Title Court or the Federal Court. The Magistrate erred by actually saying the Native Title Tribunal, as it is the Federal Court that deals with Native Title determinations, but Justice Philippedes made no comment about this error.

The Supreme Court of Queensland then went on to look at the argument put in the originating application to the Supreme Court by the Euahlayi Peoples via Ngurampaa Ltd, because there was a number of matters which raised questions of international law. Namely, that there is a pre-existing and continuing sovereignty of the Euahlayi Nation and Peoples under our Law and custom; we govern and governed and did ceremony through our connection to Country; have relationships with other tribes and Nations which were and continue to be religious in nature through the Dreaming Songlines, which govern what we consider to be inter-nation relations and intra-nation relationships domestically. These were, and are, central to our governing principles on inter and intra state relations between the Nations. and these processes were, and are, Acts of State.

Tony Abbott delivers the keynote address at The Australian-Melbourne Institute conference

But the Queensland Supreme Court continues to rely on the notion of terra nullius for its basis of sovereignty, that is, First Nations and Peoples are essentially 'backward Peoples' with no laws governing inter-nation relations. Therefore the colonial courts could rule that we did not have any system of governance that is acceptable to the British and later the Australian legal system and in their opinion our governance does not equate to an ancient Act of State prior to the British invasion.

In drawing this conclusion clearly Justice Philippedes is more interested in preserving the status quo than dealing with justice, when she argues that British settlement and British acquisition of sovereignty over occupied lands is the only Act of State that can be considered to be legally sound. She thereby confirms that the Crown's sovereignty is not justiciable in the Supreme Court of Queensland or any other court in Australia. She concluded that Magistrate Ryan in the St George lower court was correct to dismiss our application that the constitutional issues on the Rates Dispute case should be referred to the High Court of Australia under section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903.

The conclusions made by Justice Philippedes emphasised that an application by Aboriginal people that in any way challenges the legality of the sovereignty acquired by the British over any part of Australia faces 'insurmountable difficulties'. She said this question was confirmed by the High Court Chief Justice Mason in Coe v Commonwealth (1993) 118 ALR 193 when he quoted

Mabo at paragraph 27:

Mabo (No. 2) is entirely at odds with the notion that sovereignty adverse to the Crown resides in the Aboriginal people of Australia. The decision is equally at odds with the notion that there resides in the Aboriginal people a limited kind of sovereignty embraced in the notion that they are "a domestic dependent nation" entitled to self-government and full rights (save the right of alienation) or that as a free and independent people they are entitled to any rights and interests other than those created or recognized by the laws of the Commonwealth, the State of New South Wales and the common law. Mabo (No.2)denied that the Crown's acquisition of sovereignty over Australia can be challenged in the municipal courts of this country.

In this statement there is a tautology because Mabo (No. 2) concludes that Aboriginal ancient customary laws survived British sovereignty and it is these laws that underpin Native Title to our ancient homelands. The High Court in Mabo (No. 2) also said that Aboriginal law and customs do not have their foundation in the common law of England, but are themselves laws of the land and that the common law of England and Australia now recognise them as sui generis (unique). If this is not so, then our Peoples would not be able to claim Native Title. This is the tortuous nature of Chief Justice Mason's conclusion, namely the courts are trying to have their cake and eat it at the same time. Any notion of true justice here is non-existent.

Further to this Justice Philippedes draws on Chief Justice Mason's decision in Walker v The State of New South Wales (1994):

There is nothing in the recent decision in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) to support the notion that the Parliaments of the Commonwealth and New South Wales lack legislative competence to regulate.or affect the rights of Aboriginal people, or the notion that the Application of Commonwealth or State laws to Aboriginal people is in any way subject to their acceptance, adoption, request or consent. Such notions amount to the contention that a new source of sovereignty resides in Aboriginal people.

If we are to take this conclusion on face value there is something dreadfully wrong. While accepting our Law is the Law of the Land the courts vigilantly uphold the skeletal framework of the colonial legal system by expanding the doctrine of terra nullius.

We do, however, accept that the Australian courts cannot recognise sovereignty of our Nations and Peoples, because all the laws of the Commonwealth and States would immediately become null and void. This is articulated in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2), which states that, as the body of laws created in Australia's settlement are the body of laws that established validity for the establishment of the nation state, it is this body of laws that provides stability for Australia's skeletal political and legal framework. They rely upon this colonial skeletal framework to suppress and oppress our inherent rights, as they attempt in vain to maintain that somehow the Crown, in right of the States and the Commonwealth, gained the legislative rights to override our ancient laws and to make them subject to theirs, when we know that there is no legal precedence anywhere in the world for this.

For the High Court and other courts of Australia to say that Aboriginal people are somehow claiming a 'new' source of sovereignty is indeed a legal furphy, because the laws, recognised in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) as being the source of law that underpins our Native Title rights and interests in land, have survived British sovereignty.

It is my contention that most legal scholars would agree that what Mabo (No. 2) did was to recognise the pre-existing ancient common law as the continental common law belonging to the Nations, as was decreed to us through the Law of the Dreaming, just as they argue their divine right comes from their God.

What we have in Australia is a true confrontation of two contesting sovereignties. One, First Nations Peoples whose customs and laws do not reach down to the depravity based on killing and invading people to take their resources and land. The ancient Rules of First Nations and Peoples in Australia clearly defined mechanisms between one Nation going against another for resources, their territory or their women. We were not subject to constant invasion and upheavals because of religious ideologies and power to control resources, nor did our ancient laws and religion decree to us domination over Nature.

The confrontation we have in Australia has to be settled without emotive rhetoric founded on fear. Unfortunately it appears that the judges of the Australian courts have become the protectors of this questionable regime that exists in Australia.

But as the High Court said in Commonwealth v Yamirr that the:

...critical question for a municipal court is what reach the Sovereign claims for itself, not

what reach other sovereigns may concede to it.

It is very clear that as a matter of law, domestic courts cannot act upon any assumption of competing sovereignties. For any court or any body to do so would be to contravene all established colonial laws in Australia.

In this Rates Dispute case the Queensland government and the Balonne Shire submitted to the Supreme Court of Queensland:

...that they do not possess documents/ contracts/ Treaties of surrender by the Euahlayi Peoples as a result of being defeated in a declared war, nor do they possess any documents relating to the Euahlayi People ceding to the English Crown.

The fact that these documents do not exist is a lacuna (gap) in Australian colonial law, as thestate of New South Wales is unable to prove how Euahlayi Allodial title to land transferred legally to the colonial state of the Crown.

Justice Philippedes in her judgment agreed with Balonne Shire Council that Mabo No. 2 established that:

At the time of acquisition of Australia sovereignty, international law recognised acquisition of sovereignty not only by contest, cession, and occupation terra nullius, but also by the settlement of inhabited lands whether that process of “settlement” involved negotiations with and or hostilities against the native inhabitants. The High Court recognised this last mentioned method of the acquisition of sovereignty as applicable in the case of sovereignty. Those submissions are correctly made.

If we are to accept this then the High Court confirmed the expansion, not the denial, of the concept of terra nullius.

This position is clearly contrary to the International Court of Justice decision in the Western Sahara Case [Western Sahara Advisory Opinion of 16 October 1975] and no doubt accounts for Balonne Shire Council's erroneous submission, in my opinion, that:

(c) the International Court of Justice has no jurisdiction or power to interfere with the sovereignty of the Australian Crown or with Australian domestic laws;

I note that Justice Philippedes failed to refer to Balonne Shire Council's assertion that the Commonwealth of Australia is not bound to the UN Charter.

[ See link:http://nationalunitygovernment.org/content/charter-united-nations-does-n... ]

Tony Abbott's dismissive statement on the evening Justice Philippedes delivered her judgment on Euahlayi Rates Dispute case confirms the struggle the Commonwealth of Australia has in establishing any valid sovereignty:

Our country is unimaginable without foreign investment. … I guess our country owes its existence to a form of foreign investment by the British government in the then unsettled or, um, scarcely settled, Great South Land. [4 July 2014 Sydney Morning Herald].

PM Abbott's push to have Aboriginal and Torres strait Islanders 'Recognised' in the colonial Constitution and Pearson's recent statement of 10 September 2014 in The Australian about meeting the government halfway on racial bigotry, further emphasise the legal quandary the Commonwealth of Australia finds itself in. Why else would PM Abbott announce:

The First Fleet was the defining moment in the history of this continent. Let me repeat that, it was the defining moment in the history of this continent. It was the moment this continent became part of the modern world. [30 August 2014 news.com.au]

We can only assume PM Tony Abbott looks to the Australian legal system and the appointed judges to protect the skeletal framework of not only the Australian legal system but the polity as well.

Clearly, Justice Philippedes has done her damnedest to keep Australia in the fight against Aboriginal Nations and Peoples' sovereignty. She does this at paragraph 26 of her judgment by relying on Mabo (No. 2) to deny that there existed in Australia an ancient continental common law, which has its origins in the Law of the Dreaming, subsistent common law in Australia that cannot be permanently extinguished.

Justice Philippedes completely overlooks and denies the true Law of the Land when she said:

It is clear it was the English common law, not some continental common law, which applied in Australia on the acquisition of sovereignty. … It is difficult to comprehend what point was sought to be made by this submission. It is lacking in merit.

Clearly, Justice Philippedes conveniently overlooks the fact that a Native Title application can only succeed if one can establish continuing connection to the ancient Laws and customs, all of which belong to an ancient Australian continental common law.

This statement in the Supreme Court further enhances the extension of the terra nullius concept by choosing to ignore and deny what is before them. Clearly the politicians are unable to make these decisions, but the courts are doing their job.

Justice Philippedes also says that for the Euahlayi Peoples to rely on principles of international law that recognise the rights of Indigenous Peoples, along with all other United Nations conventions and resolutions that deal with the right of self-determination, sovereignty and international wrong doings, is somehow irrelevant to the Australian situation. She alludes to the fact that it is incorrect for the Euahlayi Peoples to argue that their pre-existing and continuing sovereignty cannot be interfered with by the Australian courts. She incorrectly stated that the Euahlayi could not establish its sovereignty by way of the Euahlayi Peoples Declaration of Independence and agreed with the Balonne Shire’s argument that:

... the assertion put forward appeared to be based on the proposition that a purported act of self-determination resulted in the exclusive and absolute sovereignty of the Euahlayi Nation, invoking the doctrines of “jus cogens” and “erga omnes” and was an “Act of State”, which could not be challenged save with the consent of the Euahlayi Nation. [para 18]

I do, however, agree with the assertion made by Balonne Shire that if we, the Euahlayi Peoples, seek to invoke our international rights then we should not come before the domestic courts. I have now learnt that the courts have now accepted the argument that, if we are a sovereign People as we assert, then we should not be coming to their courts.

It is therefore imperative for all Aboriginal people to understand that if we assert our sovereignty through Declarations of Independence and in doing so establish our governing Councils of State and accede to international laws having been established by the UN, then aggression or acts by Australia against us will be deemed, under international law, as acts of war against a sovereign State and People.

It appears that this is now the point that we have reached. It is now up to the Peoples of each Nation to make their decisions on what they seek to do. An independent review by Dr Gary Lillienthal affirms my view:

It is my view that the judge has failed to clarify certain arguments, so that she cannot make required findings. Also, she has used the non-justiciability of the sovereignty issue as a link in a chain of argument. This being so, her decision evinces a gross denial of natural justice, an error of law on the face of the record, and jurisdictional error. This is so serious, it merits a complaint to the Judicial Commission.

I conclude that it is an internationally wrongful act to continue to expand the doctrine of terra nullius in order to deny First Nations and Peoples our inherent rights.