Race to protect Australia's rock art from mining, graffiti and feral animals

Half the country's rock paintings – some dating back 30,000 years – could disappear within 50 years, experts warn. Oliver Milman meets the Indigenous rangers and researchers working to protect delicate sandstone from the triple threat of mining, graffiti and feral animals

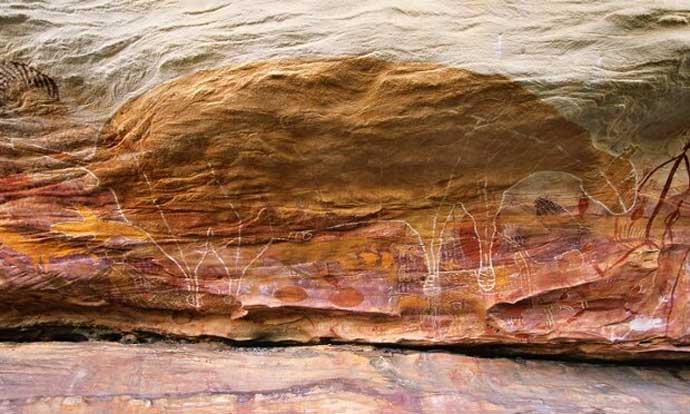

Split Rock Gallery on Cape York. The Quinkan galleries sit on a rich band of coal.

Photograph: Kerry Trapnell

Race to protect Australia's rock art: 'I don't know if we need to do an ice bucket challenge or what'

Oliver Milman in Laura, Cape York 13 September 2014

Documenting ancient rock art for a living isn't for everyone. The hours are long. The office is a dusty, rust red landscape that is regularly baked in 40C heat. The work material is often surreal, seemingly indecipherable.

But for the traditional owners of land near the remote town of Laura, a four-hour drive north-west of Cairns, the job is essential – and urgent.

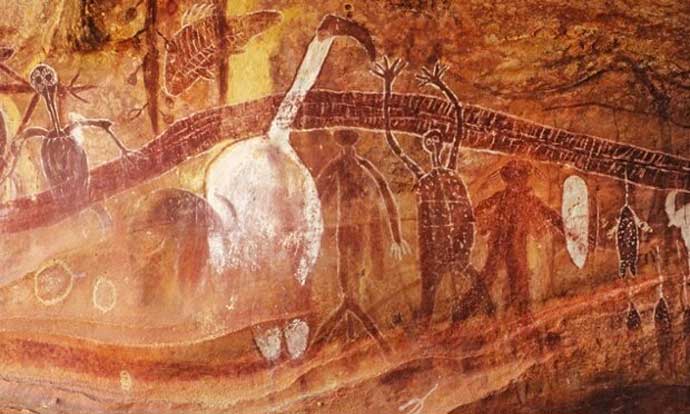

The Quinkan galleries are among the largest collection of rock art in the world, stretching over 230,000 hectares of sandstone. Dating back at least 30,000 years, the galleries take their name from the Quinkan spirits – comprising helpful protectors and mischief makers – of local lore.

Despite this heritage, the Laura region is a patchwork of mining exploration leases. Traditional owners fear any nearby mining would crumble the sandstone galleries and are mounting a rearguard action to get the area properly protected.

It's a battle that is emblematic of a quiet, nationwide struggle to preserve the art of Australia's first peoples in the face of a growing range of threats, from feral animals to graffiti. Professor Paul Taçon, a rock art researcher, warns that within 50 years half of Australia's rock art could disappear.

There are an estimated 100,000 rock art sites in Australia but there is no central register of the art and no strategy to preserve it. Worse, Taçon notes, there seems to be little interest in protect this ancient heritage.

"France and Spain spend vast amounts of money conserving their rock art, even China is spending millions and putting in a world heritage application for rock art that is 2,000 years old," says Taçon, a Canadian who has studied rock art since 1981.

"In Australia there is almost no money there for that kind of work. I don't know if we need to do an ice bucket challenge or what, but it's really difficult to get the funding to keep these areas for future generations."

Laura's rock art rangers. 'Anything hits that sandstone and bang, it's gone,' says Stephen Doughboy.

Photograph: James Norman

In Queensland, the Laura Indigenous rangers return to base on their quad bikes after a day GPS locating and photographing the array of emus, fish and spirits etched into the parched stones.

The rangers operate from a two-storey building in the centre of Laura, a small town of just 120 people. Residents struggle with high unemployment, along with other problems.

"The bush here, it's our backyard – we love it," says one of the rangers, Roderick Doughboy, leaning back in his chair, grateful for the shade. "That's why we want to hold on to it. We are the frontline, trying to stop the mining coming here."

Doughboy says he's worried that exploration could lead to trucks and drills rumbling into town. The area needs to be properly protected, he says, to allay these fears.

"We could save it now and then down the track mining could come in and we'll have the same fight over and over again," he says.

The Quinkan galleries sit on a rich band of coal that stretches across Cape York. There are rare minerals, such as diamonds, here too.

Hancock, the mining company helmed by Gina Rinehart, had a lease in the area before giving it up. Others remain – Fairway Coal, a subsidiary of Clive Palmer's Waratah Coal, is searching for fossil fuels, while the Australian Gold Corporation has two separate leases in the area. Some of these permits run until 2018.

The Indigenous rangers say the local community is united in its opposition to mining. The delicate sandstone has already been cleaved apart by vibrations from roadworks.

Rock art, Cape York

Giant Horse Gallery near Laura.

Giant Horse Gallery near Laura.Photograph: Kerry Trapnell

Doughboy's uncle Stephen, also a Laura ranger, says: "This is our heritage here, we need to keep them at bay. We want it to be here for the next generation.

"There's always a big shot who comes here to tell us which way to go. What they don't understand is that once that country goes down the drain, we don't have anything else. Anything hits that sandstone and bang, it's gone."

For Stephen Doughboy and other traditional owners, the Quinkans elicit more than just pride. It represents a visceral connection to heritage and to self. A non-Indigenous Laura ranger predicts "serious psychological ramifications" if damaging mining goes ahead.

This is all a trauma replicated across Australia – growing threats to rock art sites from developments, vandalism and damage from feral animals. "I talk to Indigenous people about these threats and they get extremely emotional," Taçon says. "These are central, tangible aspects of their culture."

Stephen Doughboy agrees. "I wouldn't be going out there on that bike for just anything," he says. "We complain about the heat and weather but at the end of the day it's something to smile about. It makes me feel prouder. It makes me feel … well." He pauses. "It makes me feel bigger."

Cape YorkA white ibis in a Cape York rock painting.

Photograph: Kerry Trapnell

Fingers are readily jabbed in the direction of the Queensland government when the lack of protection for the Laura rock art is mentioned. The government's new Cape York regional plan has sliced the vast peninsula into areas open for development, such as mining and agriculture, and zones that are environmentally protected. The Laura area falls, despite previous assurances that locals say were given to them, into the former category.

Then there is the mooted world heritage listing of Cape York, which has not just fallen off the table but seemingly been tossed into a musty cellar. The federal government missed a deadline to nominate the area to Unesco in February, although it insists the idea hasn't been completely jettisoned.

Desmond Tayley, of the Magarrmagarrwarra people and another Laura traditional owner, wants the process kickstarted to plug the gap in the Cape York plan.

"That rock art is special, it's something we grew up with and we want to protect it," he says when we meet in the nearby town of Wudjal Wudjal. "We want it world heritage-listed because we feel it may give us a higher level of protection.

This government has completely stalled the whole process and that's extremely worrying for traditional owners. We want to regenerate that discussion because at the moment we don't have any protection at all."

A spokesman for Greg Hunt, the federal environment minister, says the government is in the process of assessing "the level of Indigenous support for a world heritage nomination of appropriate parts of Cape York peninsula".

"A potential world heritage nomination for Cape York peninsula can only occur with the support of relevant parties including the Queensland government, traditional owners, industry, private landholders and the wider Cape York community," he adds. But there's no firm commitment to nominate the area by February, to facilitate a 2015 listing.

Traditional owners aren't the only ones who despair at the seemingly casual way Australia treats the heritage of its first peoples. Conservationists are exasperated by the lack of protection provided by the Cape York plan to rock art, as well as rivers and landscapes.

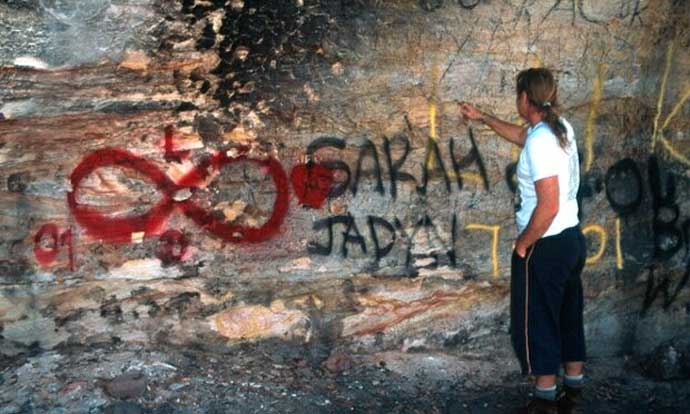

Fire damage and graffiti cover a rock art site.

Photograph: Paul Taçon

Andrew Picone, northern Australia campaigner for the Australian Conservation Foundation, says it is "deplorable" that a three-year process has led to the Steve Irwin reserve being the only area provided new protection by the plan.

"The Cape York regional plan represents one of the most significant policy failures ever delivered for the cape," he says.

"Like many parts of Cape York peninsula, the Laura sandstone escarpments are of international significance for natural and cultural values and would be central to any world heritage nomination. It is unacceptable that it remains vulnerable to mining."

Taçon, a Griffith University academic, is spearheading a seemingly thankless campaign for a national strategy to deal with what he calls a "worrying rate" of rock art losses.

Sun, rain and wind can degrade paintings, but it's the direct degradation caused by humans that most vexes Taçon.

"Graffiti is a worry and seems to be on the rise," he says. "People leave names and initials behind. Sometimes racist comments. I spoke to some Aboriginal friends from Uluru and the Pilbara and they both said graffiti is their biggest concern.

"The Quinkan galleries are outstanding and clearly of world heritage value. But we need a national strategy for rock art or it could be lost, especially if the government goes ahead with the development of northern Australia. There just seems to be a lack of will."

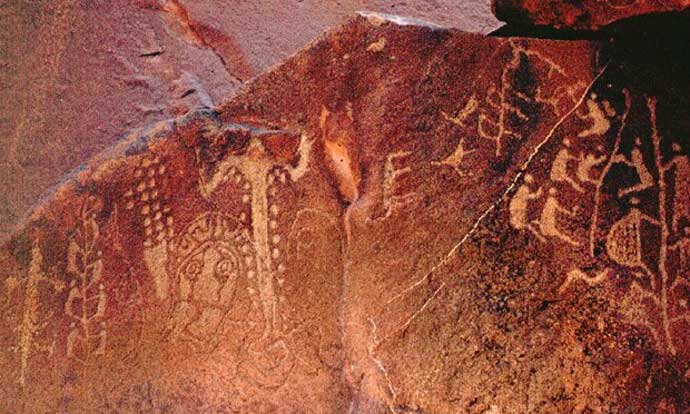

Climbing Men Panel, one of thousands of drawings and carvings on the Burrup peninsula in WA.

Photograph: Robert G Bednarik/AAP

The Burrup peninsula, one of Australia's oldest rock art sites, has suffered the ravages of the modern world. In August, traditional owners reported that several areas had been permanently damaged by people spraypainting rocks or slashing their own names into the surface. In 2009 there were reports that artefacts chipped away from the Burrup peninsula had been put up for sale on eBay.

Several years of exploratory drilling came good for the Canadian mining company Cameco last year when it found a significant deposit of uranium in Arnhem Land. Unfortunately the site is in the Wellington range, an area with thousands of rock art paintings, some 15,000 years old. One gallery complex Djulirri has 3,000 images, including the rainbow serpent, fish, kangaroos and other creatures. Cameco has promised it will work with traditional owners to protect this heritage.

Paintings in Chillagoe-Mungana Caves national park.

Photograph: Andrew Watson/Getty Images

The Chillagoe area has rock art in 41 sites, dating back 3,500 years. Fossilised bones of crocodiles and extinct giant kangaroos and giant wombats have also been found. This heritage didn't stop a mining company for drilling into the site. "They were looking for marble and they drilled holes in for dynamite," Taçon says. "After we reported it, they stopped."

A stunning stencil gallery was discovered by non-Indigenous people in 1913, when a group looking for a lost child stumbled into Red Hands Cave. Hand prints and stencils date back 1,600 years. Unfortunately, by 1934 the cave had been desecrated by people scratching their initials in the walls. A Perspex viewing window is now in place to prevent further damage. Closer to Sydney, Bull Cave in Camden, Dharawal country, has arguably fared worse. An elaborate painting of a bull on the cave wall was attacked with spraypaint, with a vandal deciding a giant penis and the words 'This is bullshit' would improve the art.