Arizona tribe set to prosecute first non-Indian under a new law

As our strong belief in self determination through the Sovereignty movement moves forward, we must start thinking about the possibilities that are before us ...

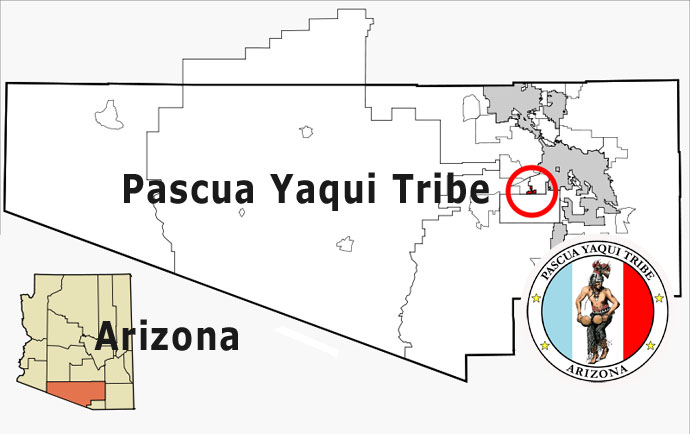

Pascua Yaqui Tribe, Arizona - Graphic by Sovereign Union (Adapted from Wikipedia)

Sari Horwitz The Washington Post 19 April 2014

Pascua Yaqui Indian Reservation, Arizona - Tribal police chief Michael Valenzuela drove through darkened desert streets, turned into a Circle K convenience store and pointed to the spot beyond the reservation line where his officers used to take the non-Indian men who battered Indian women.

"We would literally drive them to the end of the reservation and tell them to beat it," Valenzuela said. "And hope they didn't come back that night. They almost always did."

About three weeks ago, at 2:45 a.m., the tribal police were called to the reservation home of an Indian woman who was allegedly being assaulted in front of her two children. They said her 36-year-old non-Indian husband, Eloy Figueroa Lopez, had pushed her down on the couch and was violently choking her with both hands.

This time, the Yaqui police were armed with a new law that allows Indian tribes, which have their own justice system, to prosecute non-Indians. Instead of driving Lopez to the Circle K and telling him to leave the reservation, they arrested him.

Michael Valenzuela, the Pascua Yaqui chief of police

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Inside a sand-colored tribal courthouse set here amid the saguaro-dotted land of the Pascua Yaqui people, the law backed by the Obama administration and passed by Congress last year is facing its first critical test.

The Pascua Yaqui, along with two other tribes chosen by the Justice Department for a pilot project allowing the prosecution of non-tribal men, received the go-ahead to begin enforcing the law a year ahead of the country's other 563 tribes because tribal officials made the case they were able to protect the rights of the accused.

Some members of Congress had fought hard to derail the legislation, arguing that non-Indian men would be unfairly convicted without due process by sovereign nations whose unsophisticated tribal courts were not equal to the American criminal justice system.

"They thought that tribal courts wouldn't give the non-Indians a fair shake," said Pascua Yaqui Attorney General Amanda Lomayesva. "Congressmen all were asking, how are non-Indians going to be tried by a group of Indian jurors?"

Against that opposition last year, the Obama administration was able to push through only the narrowest version of a law to prosecute non-Indians. While it covers domestic and dating-violence cases involving Native Americans on the reservation, the law does not give tribes jurisdiction to prosecute child abuse or crimes, including sexual assault, that are committed by non-Indians who are "strangers" to their victims. In addition, the law does not extend to Native American women in Alaska.

"It was a compromise the tribes had to make," Lomayesva said. "It only partially fixes the problem."

Still, what will play out over the next months on the Pascua Yaqui reservation is being watched closely by the Justice Department and by all of Indian country. The tribe's officials are facing intense scrutiny and thorny legal challenges as they prepare for their first prosecution of a non-Indian man.

"Everyone's feeling pressure about these cases," said Pascua Yaqui Chief Prosecutor Alfred Urbina. "They're the first cases. No one wants to screw anything up."

Alfred Urbina, the chief prosecutor of the Pascua Yaqui tribe

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

A courtroom at the Pascua Yaqui Tribal Courthouse

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

A year ago, Urbina traveled to Washington with tribal Chairman Peter Yucupicio and others from the tribe to meet with House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, R-Va. He carried a binder with a Native American design on its wool cover that was filled with photographs of the tribe's $21 million state-of-the-art courthouse and police complex.

Most Americans have never been exposed to Indian tribal courts, and Urbina knew that there were no federally recognized tribes or Indian reservations in Virginia. Urbina wanted to show Cantor that, as one tribal official put it, "Indians were not still living in teepees" and could dispense justice as fairly as any other court in America.

Beginning with the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, Indians were encouraged to set up their own tribal courts. There are now 324 tribal courts on sovereign Indian land across the country. Most of the courts operate like other U.S. courts and have similar laws and court procedures.

But many of them also use traditional Indian culture to help resolve disputes, including elders councils and sentencing circles. The Navajo Nation has a traditional "peacemaking" program. The Tulalip Tribes send first-time and nonviolent juvenile and young adult offenders to be counseled by a tribal court elders panel, who may recommend community service and treatment instead of jail.

The prospect of exposing non-Native Americans to this system upset many Republicans in Congress. Rep. Doc Hastings, R-Wash., said the legislation made "56 million acres of U.S. soil that happen to be called Indian Country ... Constitution-free zones where due process and equal protection rights as interpreted and enforced in U.S. courts - do not exist."

Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., said it "would trample on the Bill of Rights of every American who is not a Native American."

Inside Cantor's conference room, Urbina pulled out photographs of the new, high-tech courthouse where proceedings are video- and audio-recorded and each juror has a small television screen to view forensic evidence, which is also displayed on a giant video screen in front.

Urbina, the son of Yaqui and Hispanic pecan and cotton pickers, told Cantor about his tribe, a deeply religious people who have blended Catholicism with ancient cultural traditions.

The reservation is struggling with alcoholism, substance abuse, drug gangs, teen pregnancy and domestic violence. More than 42 percent of the children are living with single mothers in poverty.

Urbina also told Cantor about all the non-Indians on his reservation, which is about two square miles in area and located about an hour's travel north of the Mexican border and a few miles southwest of Tucson. Along with about 5,000 members of the tribe, many non-Native Americans live or work on the reservation, often dating and marrying Indian women.

While some Pascua Yaqui speak their native language, almost all speak English and Spanish. Given the diversity, it was critical to be able to prosecute any men who abuse Indian women, Urbina said.

The grounds of the Casino del Sol resort (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

At the western edge of the reservation, the gleaming Casino del Sol resort brings in money for the tribe. But the casino, along with an older gambling hall down the road, is also a key to protecting criminal defendants, Urbina explained.

All employees at the casinos, including whites, African Americans, Hispanics and Asians, could be tapped for jury duty so that the pool would not be composed exclusively of Native Americans, Urbina said.

The 500 non-Indians living on the reservation could also be called for jury duty, along with non-Indians who work for the tribal government.

"Cantor came into the meeting a little perturbed," said Urbina, recalling that day. "But once we started talking and said this is what we do in Indian country, this is our court system and look, our courtroom looks like any other courtroom in America, the meeting went really well.

"He was mesmerized," said Raymond Buelna, a member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribal Council who was there. "He saw how extensive our justice system was and it just wasn't a group of people under a porch judging someone. It was an actual, living, breathing justice system."

A Cantor spokesman confirmed the tenor of the meeting. Although the majority leader was personally opposed to the prosecution of non-Indians in Indian courts, two weeks later he allowed the legislation to get to the floor of the House for a vote, and it eventually became law.

Judge Melvin Stoof

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Photos of Stoof’s grandfather, Joseph Running Bear

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Tribes that prosecute non-Indians must have a judge with a law degree, and in his office behind the Pascua Yaqui tribal courtroom, Judge Melvin Stoof has the requisite degree from The University of New Mexico School of Law on the wall, along with a photo of himself beside Attorney General Eric Holder. On his desk, he also has a photo of his grandfather, Joseph Running Bear, wearing his powwow ceremonial feather headdress.

A member of the Rosebud Sioux tribe, Stoof remembers reading in law school about the 1978 Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe case in which the Supreme Court held that Indian tribes had no legal authority to prosecute non-Indians who committed crimes on reservations.

"I never understood the logic of it," said Stoof, 57, who wears his long gray hair tied in a ponytail. "The Supreme Court found that tribal courts couldn't have jurisdiction over non-Indians because they were aliens and strangers. They didn't participate in the political process, didn't vote in elections and weren't residents. And I said, wait a minute, that's the same that would apply to a New Yorker who commits a crime in Los Angeles."

For the next nearly four decades, as Stoof served as a lawyer and then a tribal judge on 10 different reservations, he watched in frustration as non-Native American men committed crimes against Indian women and were never punished. The tribes couldn't prosecute, and the federal government, which did have jurisdiction, wasn't taking the cases, he said.

"For a long time, the federal government was not prosecuting these crimes and they didn't have to give any reason for declinations," Stoof said.

He said this was partly because some reservations are rural outposts and hundreds of miles from a federal courthouse. In other cases, federal officials and the FBI might not trust that the tribal police did a good enough job investigating and preparing the case, he said.

In Stoof's home state of South Dakota, he said, the federal government declined about 80 percent of assault and battery cases against non-Indians. But Stoof said that the number of cases declined by U.S. attorneys has dropped in recent years because the Justice Department has made an effort to prosecute more cases in Indian country.

Last year, in its first report to Congress on prosecutions, the Justice Department said U.S. attorneys declined 31 percent of all Indian-country cases submitted for prosecution.

Now, Stoof is set to be the first tribal judge in the country to hear a tribal criminal case against a non-Indian in 36 years. Since Feb. 20, when the Justice Department said the Yaquis, the Tulalip Tribes of Washington state and the Umatilla tribes of Oregon could begin prosecuting non-Indians, there have been six arrests, all by the Pascua Yaqui police.

"It's uncharted territory, and people will be paying attention to what happens here," Stoof said, smiling. "There's a lot of unresolved issues, and I'm sure there will be some challenges."

Melissa Acosta is the chief public defender on the reservation.

(Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

The challenges will come from Melissa Acosta, a Mexican American woman from Tucson who commutes to the reservation every day and serves as the tribe's chief public defender.

Working down the road from the new courthouse inside a pale-beige stucco modular building, Acosta is gearing up to defend the non-Indian men accused of assaulting women living on the reservation.

Many tribal courts cannot afford their own public defender and have only "advocates" without law degrees to defend the accused. The Yaquis wouldn't have been given the green light from the Justice Department to launch the pilot project without Acosta, a longtime public defender - and she knows it.

Acosta said she would like a little more respect from the federal government. "We should be over there," she says, pointing to the high-tech courthouse in the distance. "It would be great if the federal government threw some resources our way as well."

Acosta's office recently filed motions with the tribal court to dismiss the first three tribal arrests of non-Indian men, arguing that the tribe did not properly implement the new law, including notifying the public of its new jurisdiction over domestic violence cases.

Chief prosecutor Urbina has opposed the motion, saying the tribe fully complied with the Justice Department requirements. Judge Stoof has set a hearing for Friday.

In the meantime, a court date has been set for Lopez, who allegedly tried to strangle his wife. A resident alien from Mexico, he has been charged by the tribe with domestic violence aggravated assault, battery and endangerment. If convicted, he could face deportation. He has pleaded not guilty.

(Jahi Chikwendiu / The Washington Post)

A 37-year-old Asian man, Myxay Yongbanthom, has also been charged with domestic violence under the new law after allegedly breaking down the door of his Indian girlfriend's bathroom, where she had locked herself and her daughter to get away from him.

Another non-Indian, Tony R. Slaton, has been charged with aggravated assault and battery. Tribal police said he attacked his girlfriend in the middle of an intersection in broad daylight in front of several witnesses. He allegedly choked his girlfriend as she held onto her baby, threatened to kill witnesses who came to the woman's aid and then fled the scene, the police said.

Three other cases, including one in which an Indian woman was allegedly punched in the face and suffered a concussion, were dismissed by the tribe after evidentiary issues arose and there were questions about whether one of the victims would testify against her boyfriend.

Pascua Yaqui Victim Services Manager Canada Valenzuela said that women in the middle of domestic violence cases often want their husbands or boyfriends to come back home and not be sent to jail.

Dismissing some of the first cases was "very disappointing, but you have issues in almost all domestic violence cases, especially where those relationship dynamics are still going on," Urbina said. "It's probably more difficult on reservations where it's a small community, folks all know each other and many are related."

Whatever happens, Urbina said that in the end, the significance of the new law is bigger than the first, second or third arrests.

"When you do not have an adequate system of justice or laws, it creates a perception of lawlessness," Urbina said. "In the past, I have had to face whole families and explain that we could not provide the full measure of justice their loved ones deserved. When you have decades of this legal sickness festering in tribal communities, it has a tremendous impact on the health and wellness of tribes."