The stolen Wandjina totem takes Cultural Appropriation to a new level

Protection: To explain current protection simply, an Aboriginal Artist is protected against people copying their specific works, but as far as current laws are concerned - anyone can abuse and misuse cultural icons/totems whenever they choose. Artists in Black, which represents First Nations artists, communities and arts organisations have been working on getting a commitment from governments to provide cultural protection, but have so far been unsuccessful. More here

Vesna Tenodi at the 'Wanjina Watchers' exhibition by Gina Sinozich at the Governor's Palace in Rijeka, Croatia.

21 January 2017 (Updated in 2017 & 2018)

A Croatian born artist Vesna Tenodi who has an Art Centre in the Blue Mountains stole the sacred image of the Wandjina in 2009 and commissioned a large Wandjina sculpture at the front of her gallery and has produced many contemporary works misusing the sacred image ever since.

Many of the local First Nations people objected strongly and a Worora Tribal custodian of the Wandjina travelled over 4,000 kilometers from West Kimberley to tell her the statue seriously offended his people, but she discarded what he said by saying her actions were a "revival of Aboriginal spirituality", even though she was born on another continent and the culture of the sacred Wandina is still practiced by its peoples.

It took many months and strong protesting by local people before the statue was finally ordered to be removed by the New South Wales Land and Environment Court over a permit technicality.

Tenodi has had online and Sydney Street protests regarding what she calls inappropriate censorship.

The Wanjina Spirit

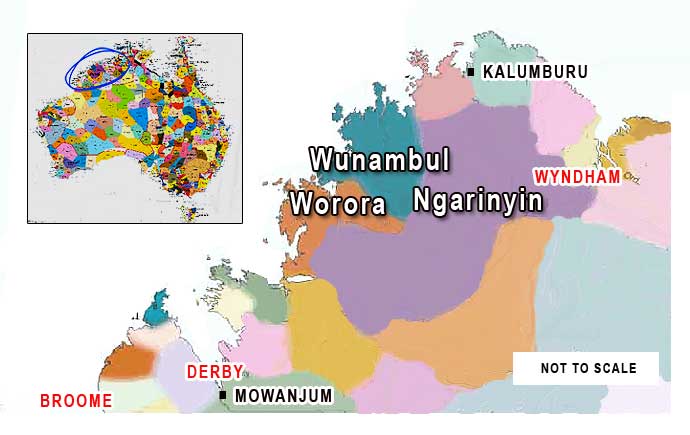

The Worrora, Ngarinyin and Wunambal people from the Northern Coastal region of the Kimberley can trace their ancestry directly back to the Wandjina spirit ancestors. Dreamtime stories say the Wandjina created the landscape and its inhabitants, the many stories associated with the Wandjina are represented in these paintings.

Only people who know the stories about the Wandjina are permitted to produce these sacred images and in current times the people from these tribes maintain the many ancient cave images and paint Wandjina'a on bark and canvasses.

Under the guidance of the people, the Wandjina was used in the closing ceremony of the Sydney Olympics and more recently at 'Lighting The Sails: Songline', Vivid Live 2016, at the Sydney Opera House on Bennelong Point. The Wandjina being used at the Sydney events were not taken lightly and carried out under the supervision on Donny Woolagoodja (1947 - 2022), a senior Worora cultural custodian.

The Cultural Appropriation

1 that ignores its cultural significance. More

947

"Some of the locals are going on with the whole 'you are stealing our culture' routine," Osvath says. "But I am an art teacher, and in art it's anything goes."

Osvath, who was teaching at Matraville Sports High School, says there was a "vigilante thing" going on in Katoomba. The sculpture's opponents set up a website, which criticised Tenodi for holding in contempt "important spiritual beliefs".

Tenodi, who then temporarily moved to Sydney after the fiasco, claimed her Katoomba house had been vandalised. "The police advice was to cut my losses and move away while we can," she says.

Asked if she had sought permission to use the image, Tenodi says she did not need to. "It was actually the other way around - the spirits asked me to do this. They asked me to revive the tradition which has turned into dead knowledge, and I agreed."

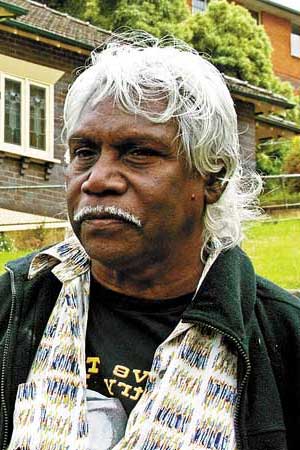

When Donny Woolagoodja (1947 - 2022)xa leading elder of the Kimberley 'Worora' tribe found out about the Wandjina being misused he was shocked, and he traveled to Katoomba on March 13 2010 to express his concern over the "inappropriate use" of Wandjina images, which he said are an integral part of the living sacred tradition of three tribes who live at *Mowanjum Community near Derby, Western Australia.

Mr Woolagoodja, chairman of Mowanjum Artists Spirit of the Wandjina Aboriginal Corporation, claimed attempts to engage Vesna Tenodi in meaningful conversation were unsuccessful.

He said she directed him to read the plaque near the sculpture and to read her book called 'Dreamtime Set in Stone: The Truth About Australian Aborigines', as this would explain everything.

"We feel we are being disrespected by what the lady is doing," Mr Woolagoodja said.

"She is taking the spiritual being that belongs to the three tribes at Mowanjum — the Worrorra, the Ngarinyin and the Wunambul.

"When she rang Mowanjum Art Centre they said no to her, she did not get any agreement and put all these things up without our permission.

"Culture is very important for our community, especially for our young generation. If they see something like this happen, it's very bad.

Wanjina Watchers exhibition by Gina Sinozich at the Governor's Palace in Rijeka

"The people in NSW, they've got totem that we don't go and copy — we respect them and any other people should respect our way of life, our images."

According to Mrs Tenodi's book "those who matter" were consulted, but when it came to being more specific she refused to answer any questions.

Threats were made regarding the sculpture and it was vandalised the night before its official launch on March 6th 2010.

Regarding the threats to the gallery owner, Chris Tobin conceded that such threats may have been made "in the heat of the moment" but "we do believe there will be spiritual repercussions for Vesna for doing these things".

Misappropriation of Aboriginal culture is hardly new. In 1997 the Aboriginal artist Eddie Burrup was unmasked as being a non-indigenous painter, Elizabeth Durack; a year later, one of the brightest stars in Aboriginal art, Sakshi Anmatyerre - whose buyers included the Sultan of Brunei, the Brisbane Broncos, Paul Hogan and the Packer family - turned out to be an Indian artist named Farley French.

More recently, Mayvic, a wholesaler of household goods, was forced to withdraw "authentic" Aboriginal rock art magnets after the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission raised concerns.

But Vesna Tenodi has been unmoved. "And we'll keep on doing it no matter what the local community might say. Besides, the stone has become a landmark. Soon it will be better known around the world than the Three Sisters."

The inadequate colonial Laws of Protection

The Arts Law Cenre of Australia said the Dharug and Gundungurra Aboriginal people of the Blue Mountains area were mortified that this conduct was occurring on their traditional lands and felt embarrassed and responsible. All five groups were upset by the unauthorized and disrespectful appropriation of important cultural imagery.

(Blue Mountains Gazette)

They contacted the group 'Artists in the Black'.

They stated on their case studies page that although the sculpture was clearly a Wandjina, it did not appear to be a copy of any particular artwork by a known artist and therefore no complaint about infringement of copyright could be made. Copyright protects individual creators of artwork – this situation concerned rights regarded as traditional or communal rights to an aspect of Indigenous culture (also called Indigenous cultural intellectual property or ICIP). Artists in the Black has long been advocating for protection of ICIP but legislative reform is yet to occur. We looked for another solution.

They went on to say that this case highlights the current gaps in protection provided to Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP) under Australian laws. It also illustrates how sometimes other laws can be used to protect cultural heritage.

'Artists in the Black' hopes that this case can be used to demonstrate the need for stronger legislation to protect ICIP.

Sharing the culture

Donny Woolagoodja is a renowned Kimberley artist whose giant Namarali Wandjina featured in the opening ceremony of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games and Vivid Sydney 'songlines' projection show in 2016. He is the chairman of the Mowanjum Artists Spirit of the Wandjina Aboriginal Corporation.

Born at Kunmunya Presbyterian Mission, Donny was moved along with his family to Mowanjum (meaning 'Home at Last'), well south of their Worrora homeland. There he watched his elders paint the Wandjinas on bark and boards, and learnt the stories of Lai Lai (creation).

His father was Sam Woolagoodja, one of the last law and medicine men of the Worora people. After his father’s death in 1979, Donny took on responsibility for the land and for the passing on of cultural traditions. He leads walking and camping tours in the west Kimberley, educating younger generations in cultural law and the importance of the land.

Donny co-wrote Keeping the Wandjinas Fresh with Valda Blundell, published by Fremantle Press in 2005. It traces the story of his cultural inheritance, as well as the role his father played in maintaining sacred Wandjina cave paintings.

The Wandjina featured in the opening ceremony of the 2000 Olympic Summer Games in Sydney (Mowanjum Artist and Worora cultural adviser, Donny Woolagoodja 1947 - 2022)

'Lighting The Sails: Songlines' was a spectacular light installation at the Sydney Opera House at Bennelong Point as part of Vivid Sydney 2016. These images were provided by Donny Woolagoodj, Mowanjum artist and Worora cultural adviser, Donny 1947 - 2022)

Location Map of the Worrorra, the Ngarinyin and the Wunambul lands (AIATSIS Tribal - Language Group Map 1994)

* Although many of the Worrorra, Ngarinyin and Wunambul peoples now live in Mowanjum near Derby, West Kimberley, some members of the three tribes also live at Kalumburu (East Kimberley) and in Homeland outstations throughout the Kimberley northern coastal region. (some of these tribal names have varied spellings - generally understood pronunciations are: wor-ora, narin-yin, wunam-bool.)