Possibly the largest collection of First Nations Artifacts was destroyed in 1882 fire

An ethnographic exhibition of First Nations artifacts and items that had been stolen, traded or collected as trophies by the colonisers during the first 100 hundred years of the slaughter and displacements were displayed in a seven-month-long exhibition, which received over one million visitors.

This would have been the largest collection ever to exist of First Nations cultural and extraordinary objects when they were placed in storage within a large predominantly-wooden building called the Garden Palace, but the palace and its contents were completely destroyed when the building burned to the ground in 1882.

Lithograph, "Burning of the Garden Palace, Sydney", Gibbs Shallard and Company, Sydney, 1882.

(Image: Kaldor Public Art Projects/Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney)

From an article by Jaren Richards, Australian Geographic 30 September, 2016 - edited by Sovereign Union

In 1882, a three-year-old palace at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden was destroyed by fire – and with it, thousands of Indigenous artifacts. The new barrangal dyara (skin and bones) installation is a reminder of what was lost. (story below)

On 22 September 1882, a fire swept through the Sydney Royal Botanic Garden, reducing both its Garden Palace and large catalog of Indigenous cultural objects to ash. As part of the Gardens bicentenary celebrations, and to commemorate the loss of these artifacts and associated Aboriginal knowledge, Jonathan Jones has created an installation called barrangal dyara (skin and bones), which traces the building’s physical outline with 15,000 ash-white shields.

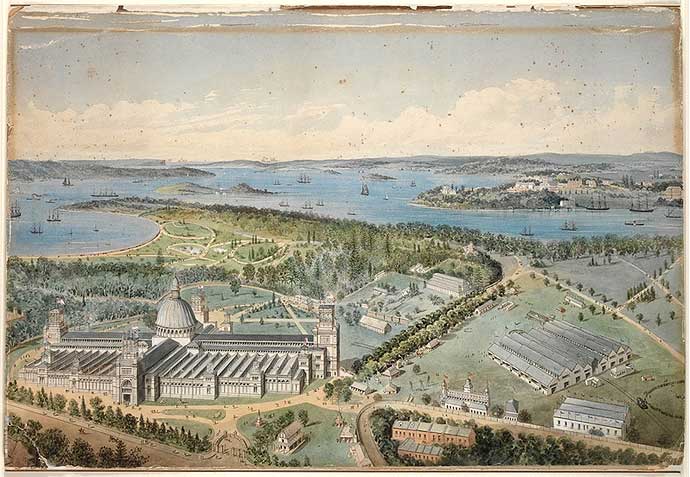

Commissioned by New South Wales premier and federalist Sir Henry Parkes, the Garden Palace opened in September 1879 for the Sydney International Exhibition, the first world’s fair held in the Southern Hemisphere. Architect James Barnett modeled the cathedral-like building on London’s Crystal Palace. It was built in just eight months. With a floor area of 20,000sq.m, the palace was three times the size of Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building and towered over the city as a grand declaration to the world of the colony’s sophistication.

The palace was filled with displays celebrating Australia’s major exports: wheat, gold and wool. The exhibition also included an ethnographic exhibition of Indigenous artifacts and items that had been traded by Aboriginal communities over the previous hundred years. At the end of the successful seven-month-long exhibition, which received over one million visitors, the artifacts were placed in storage in the palace. When the predominantly-wooden building burnt down three years later, these items and their inherent cultural links were lost.

The 'Garden Palace' was specifically built for the Exhibition and fabricated in a hurry, principally out of timber, but they not only kept it after the exhibition, they also used it as a storage place for examples of their treasures stolen whilst raping the lands, their hallowed European artefacts and the large collection of curiosities, tools and artifacts which rightfully belonged to the First Nations peoples. After the fire, the colonisers consistently spoke of the financial costs and loss of government records but seldom mentioned are the First Nations Cultural losses.

Building Details

A reworking of London's Crystal Palace, the plan for the Garden Palace was similar to that of a large cathedral, having a long hall with lower aisle on either side, like a nave, and a transept of similar form, each terminating in towers and meeting beneath a central dome.

The dome was 100 feet (30.4 metres) in diameter and 210 feet (65.5 metres) in height. The building, constructed primarily from timber, was over 244 metres long and had a floor space of over 112,000 metres with 4.5 million feet of timber, 2.5 million bricks and 243 tons of galvanised corrugated iron.

The building was similar in many respects to the later Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne. Sydney's first hydraulic lift was contained in the north tower.

The Garden Palace was sited at what is today the southwestern end of the Royal Botanic Garden (although at the time it was built it occupied land that was outside the Garden and in The Domain).

Source: Wikipedia

From a Collection of 27 illustrations and a letterpress pamphlet entitled Destruction of the Garden Palace by Fire.

(Image: Josef Lebovic Gallery)

From a Collection of 27 illustrations and a letterpress pamphlet entitled Destruction of the Garden Palace by Fire.

(Image: Josef Lebovic Gallery)

(State Library of New South Wales)

Jonathan Jones, barrangal dyara 'skin and bones' (Image: Art Almanac'

Jonathan Jones, a Wiradjuri and Kamilaro man and mixed-medium artist who with barrangal dyara bought the little-known tale of the loss of these artefacts to a wider audience in 2016; the white shields, based off traditional designs from South-eastern Australia, trace the border on which the palace once stood.

Jonathan Jones, barrangal dyara 'skin and bones'

(Image: Art Almanac'

Jonathan Jones with prototype ceramic shield on site at the Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney. (Photo credit: Emma Pike/Kaldor Public Art Projects)

Jonathan explains that the artwork is intended to both commemorate the loss and celebrate Indigenous resilience: “Barrangal dyara is a response to the immense loss felt throughout Australia due to the destruction of countless culturally significant Aboriginal objects,” he says. “It represents an effort to commence a healing process and a celebration of the survival of the world’s oldest living culture despite this traumatic event.”

A variety of Indigenous languages, including the Sydney language, Gumbaynggirr, Ngarrindjeri, Paakantji, and more, were projected through speakers into the space. Jonathan, among others, joins them; he provides free talks daily at 12.30pm.

Barrangal dyara (skin and bones) was held at the Royal Botanic Gardens. www.kaldorartprojects.org.au/project-32-jonathan-jones