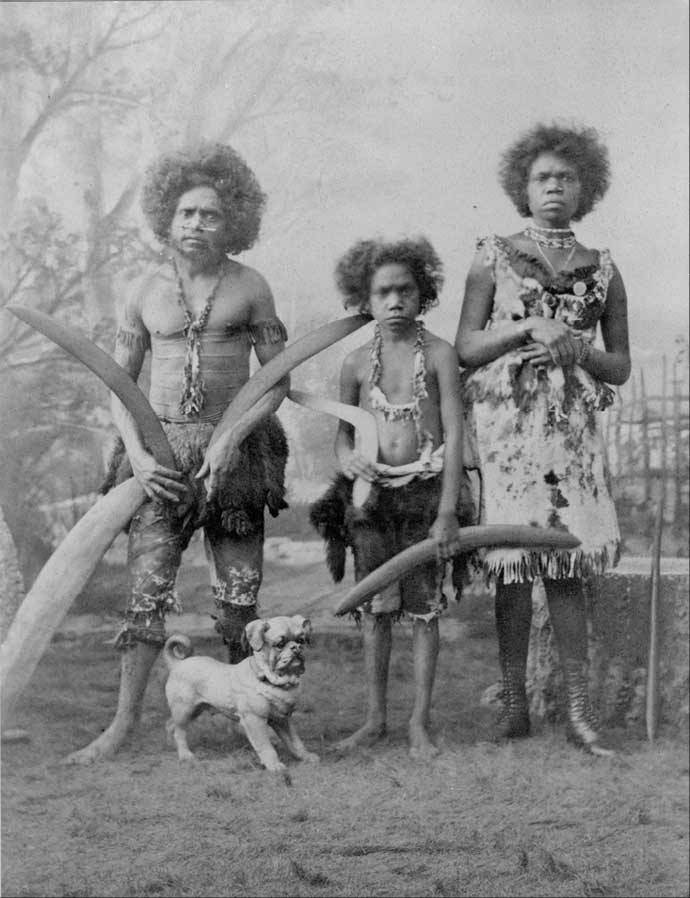

Aboriginal Slaves carted throughout USA and Europe as 'Circus Performers'

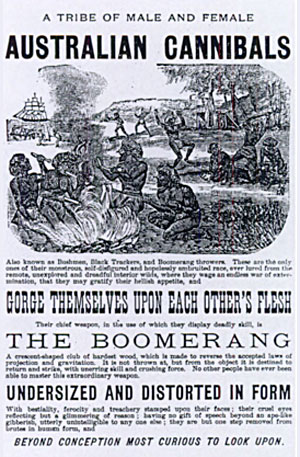

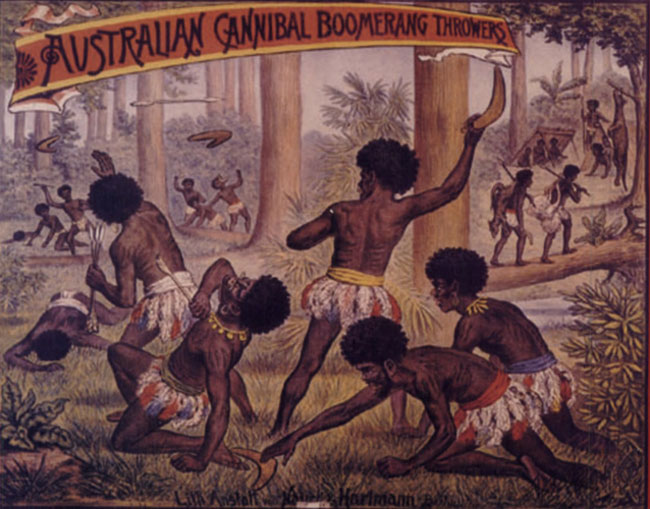

In August 1882 the circus impresario P. T. Barnum called for examples of "all the uncivilized races in existence.” In response, the showman R. A. Cunningham shipped two groups of Australian Aborigines to the United States. They were displayed as "cannibals” in circuses, dime museums, fairgrounds, and other showplaces in America and Europe and examined and photographed by anthropologists.

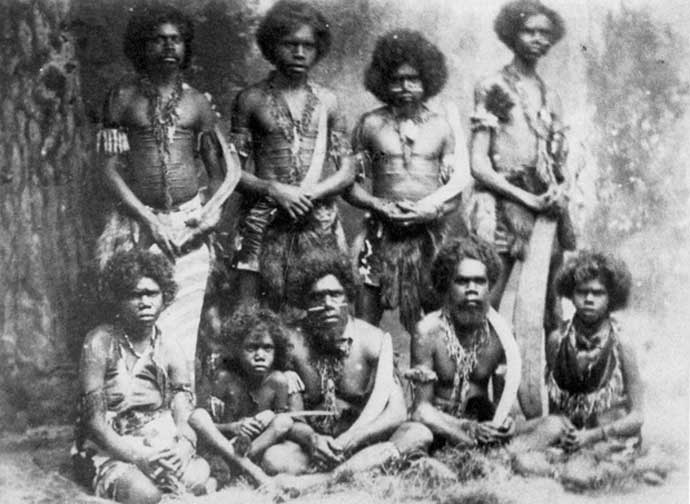

Tambo (likely the man sitting second from right), was one of 9 Aborigines who were circus performers in the 1800s.

(J Cassady - Australian Geograhic)

Carolyn Barry 8 June 2012

A gruesome discovery revealed the fate of Tambo, an Aboriginal man put on show in the USA in the 1800s.

In the depths of a basement at a nondescript funeral parlour in suburban America, a surprise discovery began the unravelling of a fascinating and convoluted tale stretching all the way back to 19th-century north Queensland. The find revived an almost-forgotten story of indigenous history and brought some closure for descendants of a group of Aboriginal men and women whose fates, until then, were unknown.

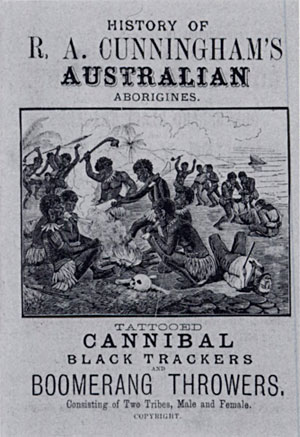

Cover of English edition of pamphlet

R A Cunnungham's Australian Aborigines

In 1993 staff at J.C. Smith’s funeral home in Cleveland, Ohio, were clearing out the building after the business closed, when one of them uncovered the mummified body of an Aboriginal man. Tambo, as he was known by his English name, was one of 17 indigenous men, women and children – including his wife – who were ‘recruited’ as star attractions in Barnum and Bailey’s famous circus during the 1880s and ’90s.

Coincidentally, anthropologist Roslyn Poignant, an honorary research fellow at University College London, had been researching the history of Tambo and his kin and was in the USA at the time of the discovery. “It was remarkable that Tambo had escaped either being consigned to a pauper’s grave or having his bones deposited in a museum,” writes Roslyn in her book Professional Savages: Captive lives and western spectacle. The discovery gave Roslyn new leads in piecing together the fates of these people, a quest which took her across three continents.

The story begins in 1883 on Hinchinbrook and Palm islands, in Far North Queensland. Robert A. Cunningham, a recruiter for Barnum and Bailey’s circus, had travelled there to find subjects for his next show-stopping exhibition, Ethnological Congress of Strange Tribes. He sought to add to his collection of indigenous people, which already included Zulus from Africa, Toda from southern India, Nubians from southern Egypt and Sioux from the USA.

It is still unclear just how forcefully Cunningham persuaded his subjects, but the records show that six Aboriginal men, two women and a boy from the Wulguru clan on Palm Island and Hinchinbrook made their way to Chicago by ship in 1883. More than likely, Cunningham tricked them or offered incentives, such as clothing and the promise of adventure. “Displacement and dispossession in the colonies, chance and curiosity” may also have played a role, writes Roslyn. Only two of the first group spoke any English and records indicate they went with Cunningham willingly.

Promoted as ‘Australian cannibals’, they performed – alongside Jumbo the elephant – dancing, singing and throwing boomerangs to delight the crowds. More than 30,000 people came to see these ‘Australian savages’ on their first day in Chicago. “I think it would have been the most horrific experience,” says Jacob Cassady, who runs a small museum and tourism venture on Aboriginal history and culture at Mungalla Station in north Queensland. This includes an exhibition about the story of these people. A large, softly spoken man, Jacob is a descendant of Tambo. “They wouldn’t have even known what an elephant was,” he says. “And they would have been missing their family and were unable to carry out traditional ceremonies.”

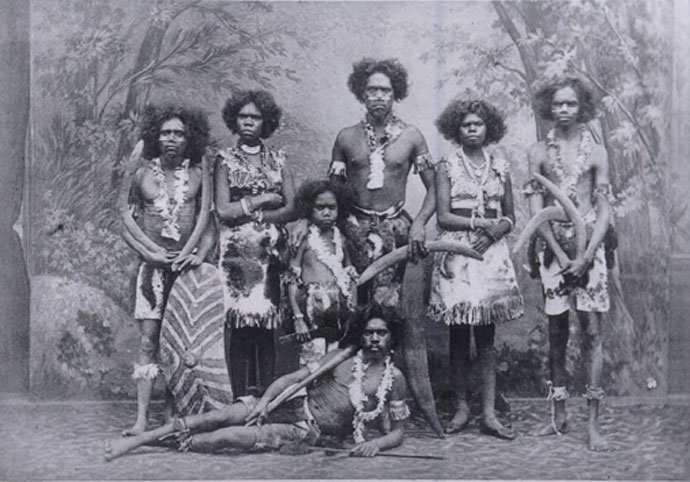

Aboriginals "removed" from Queensland (From a Postcard collected by Australian archaeologist Roslyn Poignant)

('Professional Savages' Book by Roslyn Poignant)

The group toured the dime museums and fairs of the USA, which were famous for their ‘edutainment’ – entertainment and moral education for the working class. Other attractions included bearded women, people with disfigurements, dwarfs and giants, among others.

Page 7 'Advance Courier' Australian Cannibals 1883

(Professional Cannibals page 91)

From the USA to Europe and Russia, the group allowed themselves to be measured by anthropologists and they posed, apparently unforced, in European clothing for photographs, Jacob says. “But when you look into their eyes – they tell a different story,” he adds. There was evidence they were given some money and some freedom at the end of a performance season, but the group was heavily reliant on Cunningham for food, shelter and medical care.

It’s believed Tambo succumbed to tuberculosis or pneumonia barely a year after leaving Australia – it’s unclear how old he was when he died. Cunningham was persuaded to hand over Tambo’s body for permanent display – and before the traditional death rituals could be completed, the corpse was taken away and embalmed. “He was subjected to a final, terrible indignity,” writes Roslyn. “His embalmed body was placed on show in Drew’s Dime Museum, and it remained on display there and elsewhere in Cleveland until well into the 20th century.”

One by one, members of the group fell ill and died. By 1885, just three remained: Jenny, her son Toby, and Billy. It’s thought the trio eventually went back to Australia with Cunningham, but the records are unclear. Cunningham returned to Australia in 1892 to recruit a second group of mostly Nyawaygi people, from Mungalla station, but the heyday of dime museums was at an end and the eight performers were less successful. Again, many died or disappeared until just two remained. They returned to Australia and were likely taken to a mission or Aboriginal reserve, where they were not heard of again. Tambo finally came home in 1994, about 110 years after he left for the USA. He was buried in a traditional ceremony led by Walter Palm Island, a descendant of Tambo, on Palm Island.

"I remember Granddad Wally [Walter Palm Island] telling me that when he was a kid that some relations were taken away to the circus, but I thought…the story was a bit romanticised," Jacob says. "But the more I heard about the story, the more I learnt about it, and the more amazed I was. It thought it was unbelievable."

Source: Australian Geographic, Jan - Feb 2012

(Photograph by Prince Roland Bonaparte. Royal Anthropological Institute, London)

Ngapartji Ngapartji: In turn in turn: Ego-histoire, Europe and Indigenous Australia

5. Layers of Being: Aspects of Researching and Writing Professional Savages: Captive Lives and

Western Spectacle

Roslyn Poignant

My book, Professional Savages: Captive Lives and western Spectacle, was the outcome of a project that extended over many years in which I aimed to make sense of, and make a narrative of, what happened to a group of nine Manbarra and Biyaygirri Aborigines from North Queensland - Billy, Toby, Jenny, Tambo, Sussy, Jimmy, and the others who were removed overseas by the showman R. A. Cunningham in 1883, and who toured extensively through America and Europe.

by Roslyn Poignant

Hardcover: 320 pages

Publisher: Yale University Press (July 11, 2004)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 030010247X

ISBN-13: 978-0300102475

By following the routes they had taken, and by drawing on sources, ranging from unreliable newspaper accounts of the period to culturally blinkered anthropological reports, as part of the process of interpretation, the visual material that I gradually assembled photographs, circus ads, posters, newspaper sketches and cartoons frequently functioned as crystallising images in which the dynamics of interaction were exposed, thereby shaping both the processes of ‘looking for’ that is, the research and the ‘telling about’ of their story. But first something about ego.

In early 2011, I attended a seminar in the October Gallery, London, led by three Indigenous Australian performance artists. One of the speakers, Fiona Foley, a Batjala woman from Fraser Island, referenced Professional Savages for the well-illustrated account it gave of the frontier wars in Queensland that had decimated her people and their more northerly neighbours.

Afterwards, when she asked me why I had made so few references to my personal involvement in the story, I reminded her of the ‘History Wars’ of the 1990s and 2000s, and told her that I thought the best way to counter Keith Windshuttle’s representation of the postcolonial rethinking of the colonial project as a Fabrication of Aboriginal History was with as carefully researched, detailed and non-partisan an account as possible ...

Article continued here

From the back cover of the book Professional Savages: Captive Lives and Western Spectacle

by Roslyn Poignant

NB: Being labelled as 'cannibals' is highly offensive to Aboriginal Peoples/FNP as the culture is very different from some of the Pacific islands cultures where cannibalism was rife and was generally contained by the coming of Christianity to the Pacific Island cultures..

Aboriginal culture is highly cultured and there are strict rules regarding which meat you can eat and without special sanctions you are not allowed to eat your totem, e.g. kangaroo, goanna, snake, etc. The Rules surrounding 'meat' are part of the balance that is maintained between humanity and the food sources.

The myth of cannabalism in Australia is part of the derogatory misinformation that opened the door for FNPs to be slaughtered as 'vermin' and to be wiped off the face of the continent in line with the now disproven concept of terra nullius - land belonging to no-one.