You are here

Search by issue

Media Releases & News

- SU Media Releases

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2022

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- General Statements

- Sovereign Treaties: International Law

- Walkout Statement from Sacred Fire

- Proclamation (with video Readings)

- UDI's Explained

- What is 'Decolonisation'?

- Uluru Statement from the heart

- Sovereign Manifesto of Demands

- NO CONSENT to Recognition

- Submission on ILUA Amendment

- Uluru Statement video testimonials

- Uluru Statement grassroots videos

- Complexity of Treaty and Treaties

- Understanding Treaty & Treaties

- Official SU Meetings

Sovereign Union Menu

- Self Governance

- International

- Treaty - Treaties

- Sovereignty

- General Principles of Sovereignty

- First Nations sovereignty defined

- The Sovereignty Debate

- Sovereignty into Governance

- Reform: Practicing sovereignty

- Sovereignty after Mabo

- What about Sovereignty?

- Current sovereignty debate

- Sovereignty protest Qld

- Research papers & Theses

- Sovereignty never ceded -thesis

- SA sovereignty challenged

- Rosalie Kunoth-Monks leads the way

- Pacific Islanders Act 1875

- Asserting Aboriginal Sovereignty

- Aboriginal rights then & now

- Michael Kirby Oration

- Academic Paper : Songlines

- John Howard recognised sovereignty

- Queen Victoria: Crown owns nothing, Aborigines sovereign

- Rejecting 'recognition'

- Yingiya Mark Guyula Speach

- New Way Summits

- Decolonise

- August

- Australia: UN Questionnaire

- July

- Law against Genocide Bill

- Rally: 'Let us go Home'

- Ray Jackson: 30 years of light

Special Features

- History

- During Invasion

- Invasion

- 1788-2014 Invasion to Resistance

- 'The condition of the natives' 1905

- Mapping QLD massacres

- Cooks Instructions & Diary

- Whites & Blacks during the colonisation in the late 19th Century

- Australia's history of slavery

- Dad 'n Dave - The Qld killing fields

- Treatment of Aboriginal Prisoners

- 'Conspiracy of silence' blood baths

- British Parliament Report 1837

- Culture

- Horrors of North West WA

- Ignorance & Racism

- Invasion

- Post Invasion

- Stolen Remains and Collections

- Culture

- Kitty Wallaby: Dreamtime & colanisation

- Improve heritage management

- Unlock secrets of rock art

- Kurlpurlunu found in Central Australia

- Forgotten' Woolwonga tribe for 130 years

- First Nations rock art is at risk

- Language diversity threatened, study

- Languages Treasure trove

- Pressure to lose values and culture

- Languages reveal scientific clues

- Ignorance & Racism

- Father of the Stolen Generation

- Aboriginal counting myth won't go away

- Pleading letters to 'Protector'

- 1926 plan for an Aboriginal state

- First prisoner abuse inquiry 1905

- Legalised slavery: hidden reality

- The second dispossession

- Rottnest Island internment camp

- Meston's 'Wild Australia' Show 1892-1893

- Stolen Wandjina: Cultural Appropriation

- Whitefellas destroyed our bible

- Fraser Island Death Camp

- Intervention to kill self-determination

- Ongoing Warfare

- Pre Invasion

- Culture

- Genesis

- Out of Australia - Not Africa

- confirmation of genetic antiquity

- WA's Mid West History 30K

- 'Australian' peoples were first Americans

- How First Nations saw the Stars

- Ice Age struck First Nations people hard

- Kimberley paintings could be oldest

- Misunderstand First Nations science

- Sea-Level recorded

- James Cook's Secret Instructions - 30 June 1768

- Trading & Hospitality

- Landcare, Science, Agriculture

- Captain Cook

- During Invasion

- The Frontier Wars

- Memorial Marches

- The Frontier Wars

- Anzac Gathering 2012

- Aboriginal servicemen honoured

- 1905 Report WA's North

- Anzac Day Videos

- Battle for FF memorial

- From invasion to resistance

- Frontier Wars Remembered 2016

- Image Galleries

- Invasion & Sovereignty

- Invasion Day Callout for 26 January

- Memorial ignores frontier war

- The Freedom Fighters

- Truth about the Gulf country

- Conflicts/Massacres

- Massacres & Trophies

- Mixed Media

- Canberra 2016

- Closing the Homelands

- Homelands explained

- Central Articles

- Closing Homelands for mining

- Vital for ecosystems

- Terra nullius never went away

- Barnett's plan to axe homelands for years

- Fed Gov't $100 million deal with states

- Mining: $10,000 job sweeteners

- Abbott rejects international law

- Barnett's War on Health

- Anatomy of Racism in 2015

- Food supply autonomy needed

- Freedom Summit: WFD Media Release

- Funding: Confusing-fractured-racist

- It's OK to discriminate

- The demise of Coonana community

- Sovereign Union Articles

- Reports by State & Territory

- Video - Images - Audio

- Rallies

- Media Reports

- Homeland Closures

- 'Recognition' Constitution

- Nuclear Waste Dumps

Key Topics & Issues

- NT Detention Hearings

- NT Intervention

- Sovereign Embassies

- All Embassies - Map

- Embassies

- Canberra Tent Embassy

- Perth Sovereign Embassies

- Portland Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Embassy - Home

- What is Brisbane Embassy?

- 2013 content

- 2012 content

- New Stolen Generation rally

- Police arrest sovereigns

- Politically motivated eviction

- Brisbane - Eviction notice

- Brisbane Embassy meets CMC

- Brisbane conference 2012

- Charges dropped but ...

- Council meets Elders

- Embassy arrestees protest

- Embassy midnight raid

- Embassy to be shut down

- Fire destroys Embassy

- Musgrave heritage listing

- Sovereigns charges dropped

- Moree Sovereign Embassy

- Broome Tent Embassty

- Woomera Sovereign Embassy

- Airds Sovereign Embassy

- Gugada Sovereign Embassy

- Tent Embassy in Airds, Campbelltown

- Call for Embassy tolerance

- Embassy Articles & Media

- Land, Sea & Water

- Northern Murray Darling Basin

- Water Treaty Talks: Murray-Darling Basin Nations

- Mining Country

- Adnyamathanha people of the rocks

- Ancient approach to global emissions

- Danger: Developing the North

- First Nations Land Management

- Historical sites in NSW

- Clark and Mansell: trading beef

- David Suzuki: Aboriginals best bet

- Dingoes may save wildlife

- Fires support mammals - research

- First Nations had villages and farmed

- Homelands vital for fragile ecosystems

- Hunter gatherers Myth - Bruce Pascoe

- Kangaroos win after hunt with fire

- Race to protect ancient rock art

- Kakadu Park 40th Anniversary

- Land rights and the government

- Native 'wild' rice in Australia

- Native Title amendments slammed

- Ngoongar Grower group using Native Youlks

- WA Aboriginal Heritage Act overview

- Sovereign Neighbours

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- December

- October 2013

- September 2013

- Emergency Protest of Illegal Deportation

- FF activists a test for Abbott government

- West Papuans Deported to Port Moresby

- Six West Papuan's flee after ceremony

- Freedom Flotilla claims success

- Sacred water and fire celebrated

- Ceremony completed in secret

- Military buildup in destination port

- Men released: Treason charges pending

- Julie Bishop incites military action

- Threats to turn back boat

- Four arrested at FF Welcoming

- Time for human rights in Papua

- August 2013

- Media Files

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- Atooi Unification Ceremony

- Atooi now has jurisdiction

- Australia & Fiji union

- Canada Day: Time of Mourning

- Canada First Nations alliance

- Canada: Commercial fishing rights

- India: Ruling against mining co

- Indigenous rights struggle

- North American Indians seek Sovereignty

- Statue honors US freedom fighters

- The Creation of one world gov't

- Vanuatu: Pacific custom land tenure

- Arizona tribal law system

- Canada: Tsilhqot'in peoples win ruling

- Embassy meets Indonesians

- Grandmothers: worst ever stealing

- Ibans acquired native customary rights

- Maori did not cede sovereignty

- UN: Canadian Aboriginals in crisis

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- The Invasion

- A day of sadness

- Health and Social Issues

- Suicides & Depression

- Suicides just happened?

- Nothing will be done about the suicides

- First Nations suicide rates

- Gov't not listening - People die

- 77 suicides in SA alone

- 996 deaths by suicide

- Hundreds will suicide if we wait

- Suicides: 'A humanitarian crisis'

- Suicide is humanitarian crisis

- Suicide epidemic worldwide

- Noongar x3 suicide rate

- Falsely arrested & drugged

- Cashless Welfare Card

- Family breakdowns causing repeats

- General Health Issues

- Government Policies

- Youth suicide at crisis point

- Negatively framing policies

- A little boy who hid under the bed

- Defend and Extend Medicare

- Call for help results in children stolen?

- Doctors in communities in WA reduced

- Children and human rights

- Our children more likely to be removed

- Justice? wake up WA

- Need for Bilingual schools

- Racism Effects

- Rosie Fulton

- Work-for-the-Dole Unhealthy

- Youth lost in prisons: Amnesty

- Suicides & Depression

- Gross Abuse

- Genocide and apartheid

- National

- States & Territories

- Suicides

- Imprisonment & Deaths

- International Critisism

- Genocide

- More Gov't Abuses

- Mining and Destruction

- Racism

- Racism Game in Australia

- 27% say it's OK to be racist

- Abbott backs out of Racism changed

- Genocide by Apartheid Australia

- How Bolt should be punished

- Racial discrimination in Australia

- Racism Media

- Racism driver for ill health

- Racism is a health issue

- Racism worse than Sth Africa

- Reform: Just Ask Black Australia

- Unpacking White Privilege

- Welcome to Dja Dja Wurrung Country

- White Australian National Anthem

- Solidarity

Media & Resources

Activism and Politics

- Activism

- Homelands

- For the record: Sovereignty Never Ceded

- Freedom Fighters memorial call

- Anthony Fernando 1864–1949

- Fernando's Ghost - Transcript

- Historic Videos and Images

- Australia’s dirty secret

- Deebing Creek development

- Pilbara pastoral strike

- Pro-Black Isn't Anti-White

- Truth Telling Uluru Statement

- UN slams anti-protest laws

- Whitlam: Legacy of Wave Hill

- Winyirin Bin Bin, Pilbara Strike

- Politics

Tasmanian First Nations peoples skulls return from Chicago Museum

The sacred remains of First Nations people from Tasmania were collected by British soldiers and settlers, who made a bundle of money scavenging the countryside for 'artifacts' and 'collectibles' to send back to motherland collectors during and following the 'Black War'.

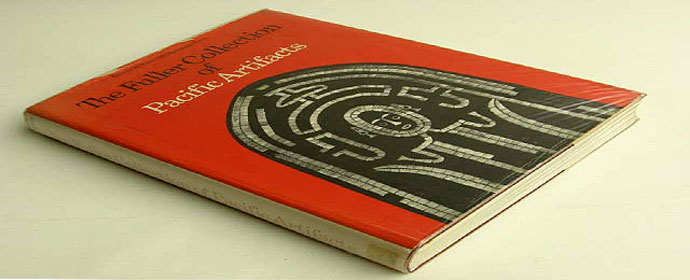

The Fuller collection of rare artifacts: Roland W. Force & Maryanne Force, Praeger, 1971 -

The skulls of Tasmanian First Nations people are within this collection at the Field Museum in Chicago

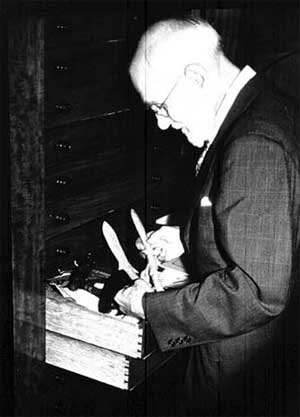

handling two whale bone harpoon heads from his collection.

Captain A W F Fuller was an armchair anthropologist and collector who amassed over 65,000 cataloged items, had a passion for ethnographic artifacts from the South Pacific region (7000 items - over 600 from Australia). He did all this without leaving his armchair in Britain.

In some instances Fuller acquired single specimens and in others he secured entire collections.

His massive collection included the sacred skulls of First Nations people from Tasmania where the British undertook a mass murder (Black War) campaign to eliminate all First Nations people.

At the time, British soldiers and settlers made a bundle of money scavenging the countryside for 'artifacts' and 'collectibles' to send back to motherland collectors.

The massive Fuller collection ended up at the Field Museum in Chicago, a place with enough space to house and display his vast amount of artifacts and bones - This is where the Tasmanian skulls are currently located.

20 June, 2014

The skulls of three Tasmanian First Nations peoples will be brought home after a Chicago museum agreed to release them.

Three First Nations community representatives are on their way to the Field Museum to collect the skulls that have been in its collection since 1958.

They were first donated to an English museum in the 1830s but their identities remain a mystery.

"There's very little known about the two donors and nothing about how they obtained the skulls from Tasmania in the first place," the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre's Sara Maynard told AAP.

The skulls are among nearly 7000 items in the natural history museum's AWF Fuller Collection.

English World War I captain Fuller assembled one of the world's most extensive collections of Pacific artefacts, including 671 items from Australia, despite never setting foot in the region.

The Field purchased his collection in 1958 but put up no barriers when asked if the remains could be repatriated.

"Unlike many museums, they agreed without fuss to return our ancestors to us," Ms Maynard said.

"The museum has been really positive and really great to deal with."

The Tasmanian First Nations community's repatriation program has notched a string of successes since Australian museums began releasing remains in the 1970s.

The British and Natural History museums in the UK, and institutions as far flung as Sweden, have released remains since the 1990s.

The community would continue discussions with the Field about cultural objects such as spears, necklaces and casts in their collection, Ms Maynard said.

"We'll be working towards the return of these over a longer period," she said.

The community will decide what further research might be done on the skulls and on a burial when they arrive next Friday.

The campaign to bring back more remains from other museums would continue, Ms Maynard said.

Tasmania's Black War: a tragic case of lest we remember?

Tasmania's Black War: a tragic case of lest we remember?

The bone collectors: Brutal chapter in Australia's past

The bone collectors: Brutal chapter in Australia's past

When will they be given an appropriate resting place?

Author writes about a fight for her ancestors remains

Author writes about a fight for her ancestors remains