Governments fail to protect one of the world's important sites from vandals

Ongoing damage by vandals, scrub fires by station owners and tourists are continually being discovered at many sites of some of the world's oldest Aboriginal carvings and paintings, which have laid undisturbed for centuries in the Pilbara and Kimberley regions of WA.

Not only are the sites vulnerable to the destruction of country meted out by some of Australia's biggest mining projects, there is also a failure of governments to protect these sites from grand theft, vandals and others, who don't seem to have any respect for First Nations culture and ancient history.

Pic: Aboriginal elders and rangers are devastated by the vandalism at Burrup

(ABC News: Ebonnie Spriggs)

Vandals have permanently damaged ancient Aboriginal rock art in Western Australia's Pilbara region, leaving elders devastated and forcing rangers to document graffiti and imitation carvings.

The damage has been discovered at the site of some of the world's oldest and largest Aboriginal carvings, which have laid undisturbed for centuries on the Burrup Peninsula, in the shadow of Australia's biggest and richest resource projects.

"This is the oldest rock art in the world, and people tend to still climb over it and do a bit of damage in all different ways," elder and senior cultural ranger Geoffrey Togo said.

"The main one we seem to be finding lately is people spray painting on rock art, and on the face of rocks, and some other old carvings.

"Some seem to be carving themselves, their name or something else, on top of old carvings."

Vandalised rock art irreplaceable, 'like Bible' for elders

Mr Togo said traditional owners were appalled.

We are also starting to see imitation carvings of maybe using hand operated tools so chisels, all that sort of stuff, but it's mainly the paint.

"It makes me angry when they do it," he said.

"You don't see myself going to church and doing the same thing in the church or someone's home.

"This is basically my backyard, well everyone's backyard really, so why go and destroy things you don't know anything about?" he asked.

Mr Togo said the art was irreplaceable.

"It's basically our Bible, or our book - you have yours written in paper, ours is written on stone," he said.

"It tells us what we need out here, or seasonal change, it tells us what animals are out here, what animals are out in the sea."

Last year, almost 5,000 hectares of the Burrup was declared the Murujuga National Park, transferring ownership of the land to the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation.

The corporation's rangers have since been managing the land, in partnership with the Department of Parks and Wildlife.

These rangers are now working to document the damage and clean it up, where possible.

The co-ordinator of the Murujuga ranger program, Sean McNeair, said the damage was in the high recreational areas.

"There are approximately 15 to 20 sites at the moment we have recorded with significant graffiti damage," he said.

"We are seeing a range of it, mostly it's painting, dating back to the old hand paints, we have spray paints, stuff like that.

"We are also starting to see imitation carvings of maybe using hand operated tools so chisels, all that sort of stuff, but it's mainly the paint."

Rangers use WiFi to highlight vandalism issue at Burrup

Mr McNeair said a system had been developed to tackle the vandalism.

"We have just done a graffiti project out at East Lewis Islands with Karratha CARE and Australian Marine Services, in conjunction with our ranger program," he said.

"There's actually a process where we can remove [some of the graffiti], and that's quite safe and non-chemical, low impact as well.

"But with some of the rock art - I don't know that some of it can be brought back to its original condition."

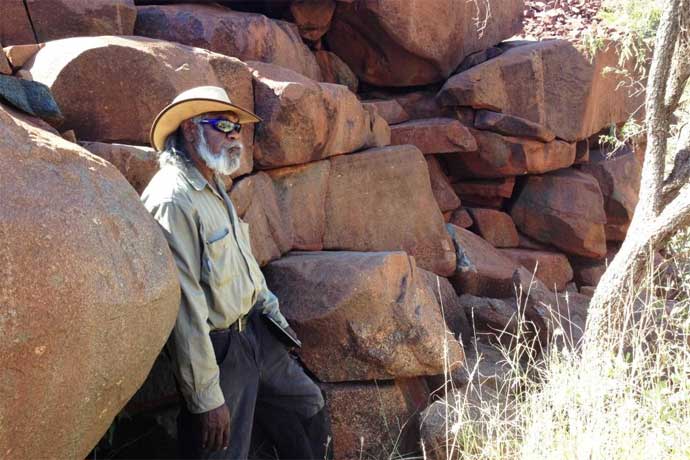

Pic: Indigenous ranger Geoffrey Togo is raising awareness of the vandalism at Burrup.

(ABC: Lucienne Bell)

Traditional owners say they do not want to have to close off areas to the public, or put up warning signs that would detract from the natural landscape.

Instead, their focus is on education and making people aware of the significance of the sites.

"What we don't want to do is make this into a signage area, completely full of signs - we want to keep it as natural as possible, so we are looking at different alternatives to do that," Mr McNeair said.

"Educational awareness is our main way of getting this message across about these culturally significant areas and what this rock art means to people, especially here on the Burrup, it's quite significant."

The rangers are highlighting the issue in a number of ways, including with a WiFi application.

"The idea is to have that maybe at the airport, where people land and at sites in the park, such as Deep Gorge," Mr McNeair said.

"It will be a free WiFi app and you can connect to it and that will show you a rock art protection video that we have made, who to contact, who else is contactable with DPAW as well, and also police, shire and other places," he said.

Rock art being mapped electronically

Cat Morgan, a cultural archaeologist, has been working with the rangers to help develop an electronic application to track and map the rock art, including graffiti damage, to replace the current paper system.

"We have come here to work with the rangers to train them up in archaeological identification and management processes," she said.

"It's a way of getting the rangers being able to manage and identify their own archaeology so they don't have to rely on external consultants, and it's a way of giving them ownership of their country and their heritage.

"Looking at how many people are visiting and if that's impacting, if there is more graffiti because there are more people, or if it's a certain type of people that are visiting that are impacting upon sites.

"Then managing that from a seasonal perspective as well, so whether there needs to be more rangers at a particular site at certain times of the year and that kind of thing."

Ms Morgan said the damage to such significantly cultural sites is not confined to the Pilbara.

"It's all over the place," she said.

"I generally have only worked in WA, but it happened on the south coast as well, and it's not just people not understanding what they are seeing, because there are places where there are signs saying 'there is rock art here, it's highly significant, it's thousands of years old' and people are still graffiting over the signs over the rock art.

"I guess it's about creating awareness and education, but at the same time there is always going to be people who even though they know, they will still do something like that.

"So hopefully at some point we can catch someone and just say these are the consequences for your action."

Ebonnie Spriggs ABC Posted here 3 August 2014