Flying Foam Massacre - The killing fields of Murujuga

Rocks placed in memory of those who were killed in the massacres just north of Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula)

By Robert G. Bednarik

The 'Flying Foam Massacre' took place just north of Murujuga (or Burrup Peninsula), in the Dampier Archipelago of Western Australia on 17 February 1868, and was only one part of an extended campaign lasting through the rest of February, and continuing in March and May 1868.

ENLARGE IMAGE

'Flying Foam Massacre' by Carl Lumholtz, 1889

During this period several massacres of Yaburara took place on and around Murujuga, so it would not be correct to describe this period of systematic extermination as a single massacre that took place in a single locality. It may be more appropriate to speak of the Murujuga Campaign, which was apparently only survived by a few individuals.

The number of Aborigines killed in this campaign is unknown, because the official report is clearly unreliable, self-contradictory and self-serving. It must be appreciated that the hostilities were initiated by a police officer, Constable Griffis, who had apparently abducted a young Aboriginal woman at gunpoint and took her 'into the bush'. He then arrested her husband, Coolyerberri, on a charge of stealing flour from a pearling boat, on 6 February 1868.

That night he and his native assistant, named Peter, camped with two pearlers, Bream and Jermyn, on the west coast of Murujuga, chaining their prisoner by the neck to a tree. During the night they were attacked by nine Yaburara men who, in freeing Coolyerberri speared Griffis to death, also killing Peter and Bream in the ensuing fight.

The Government Resident in Roebourne, R. J. Sholl, examined the site some days later and estimated from the tracks that about 100 Aborigines had been present. He swore in two parties of special constables, totalling nineteen men, and sent them to apprehend the nine Aboriginal men who had been named as the murderers.

One party moved in by land, the other by sea, sailing to the north end of Murujuga on a cutter, ostensibly to prevent the Yaburara from escaping to other islands. No handcuffs or chains to secure any prisoners were carried by the government force, and in fact only two prisoners were taken but they escaped because of this lack of means to secure them.

According to the police report, only a few people were killed when the main camp (presumably in King Bay rather than Flying Foam Passage) was located and attacked on 17 February. However, according to David Carly, a settler from Roebourne, about sixty Yaburara were killed on that occasion.

According to an old Ngarluma (or Ngaluma) man, whose information came from the few Yaburara who had survived the campaign, thirty or forty people were killed in that massacre. My own informant quoted a figure of twenty-six, but his account of Griffis’ spearing differs significantly from the police report.

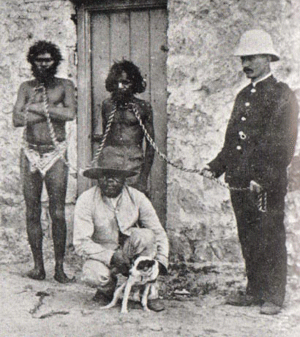

Pic: facsimile illustration

Carly reported in 1885 that he himself examined fifteen skulls at the site, three of which were of children, ‘and two of these small skulls had bullet holes in them’. The indiscriminate killing of women and children, apparently even at close range, combined with the lack of materials to secure prisoners imply that there was no intention to limit the ‘reprisals’ to the apprehension and trial of the nine men accused of killing Griffis and his companions.

This is confirmed by the events of the following ten weeks, during which an unknown number of further massacres occurred on Murujuga and nearby. Only a few such events have been recorded officially. On 19 February, Aborigines trying to cross Flying Foam Passage on logs were chased by a posse in a rowing boat and shot in the water, as were others on land nearby.

Another attack occurred on the following day, on either Angel or Gidley Island, as the distraught fugitives tried to escape to other islands. Three Aborigines were shot dead in March at Maitland River, well into the territory of the Mardu-Dunera, presumably trying to escape into the mainland.

By this time the campaign was conducted by a police party led by a Constable Francisco. In May, four more were arrested on Legendre Island, two of whom were sent to Rottnest Island Prison for twelve years. Two more men ‘gave themselves up’ in early 1869, and it is interesting that Sholl exercised ‘leniency’ then. Perhaps by that time he had realised that the campaign had not been handled in a lawful manner, and there is historical evidence that certain Roebourne residents had expressed their disgust with the extermination campaign.

On this basis it would seem that only six Yaburara survived the bloodbath, according to the official records. What was their number before these events? Sholl himself acknowledges the presence of about 100 at the site where Griffis met his fate. There is thus a substantial deficiency between the vaguely implied but unstated numbers of dead in the police records, and the number of Yaburara before the massacres.

Pic: Pilbara prisoners details unknown

Based on the demography of similarly resource-rich coastal environments as that of the Dampier Archipelago and on historical accounts, I believe that the Yaburara numbered between 100 and 200. Their numbers would have been limited by a shortage of freshwater supplies in the dry season and the need to move seasonally. No doubt some escaped the massacres by being sheltered by pearlers or settlers, and some may even have survived by hiding in the barren boulder piles of the islands, managing to avoid the constabulary.

On that basis the number killed at the initial massacre was probably somewhere between twenty-six and sixty. The number that died in the entire campaign can only be conjectured, but could have been anywhere in the order of forty to 100 (including those who may have perished subsequently, due to injuries, starvation or other circumstances induced directly by the massacres).

After the initial ambush at King Bay, hunting down small groups or individuals in the rock piles and mangrove flats would have been difficult. Perhaps the most successful strategy was to push the scattered groups into the sea, prompting them to cross to the remaining islands of the archipelago. Once in the water they were easy targets and marine creatures would have consumed their remains. The killing of three people at Maitland River later in the campaign suggests that, once escape to the islands seemed futile, some of the desperate fugitives turned south in a final attempt to break out of their predicament.

Significantly, the last contact is reported at Legendre Island, which is furthest out to sea: there was nowhere left to flee from there. The perhaps most striking aspect of the Murujuga Campaign is the almost complete absence of any captives, in fact the only prisoners seem to have been men: two were apprehended early but escaped, four were taken prisoner at the end of the campaign, and two gave themselves up subsequently.

So what was the fate of the women and children? It is not likely that they were perceived as a significant threat by the heavily armed posses, so why were they not spared and captured?

A plaque on the Burrup Peninsula in memory of the massacres

Throughout Australia, the shortage of females in frontier regions led to the practice of ‘recruiting’ Indigenous females, and in fact the Murujuga Campaign was itself ignited by this very issue.

The wholesale killing of women and children in this Campaign is therefore particularly important in understanding its agenda. I submit that this is a classical case of premeditated genocide, and that it was committed not by rogue settlers taking the law into their own hands, but by police officers and special constables working in the service of the State of Western Australia.

Therefore this seems to be a prima facie case of the state-sanctioned, intentional extermination of an entire division of the Ngarluma people.

The Yaburara occupied a specific geographical area, encompassing Murujuga, the remaining eastern part of the Archipelago, and the coastal mainland region of Nickol Bay, including what today is Karratha. They would have regarded themselves as possessing sovereignty over this land, and the government of Western Australia acquired this sovereignty by an act of genocide.

The current claims of this government over the land, its apportioning a century later of the land to various companies, its collection of royalties from these companies and its systematic destruction of the Yaburara’s cultural remains since 1964 all need to be seen in this light.

Not only do these claims need to be tested in an international court of law, there should be no doubt that the Ngarluma have a legitimate basis to seek compensation for the described action by servants of the State in 1868. Together with interest for the intervening period, such material compensation should be quite substantial.

In return, the Ngarluma community should also make reparation to the State, by returning one small bag of flour that Coolyerberri is alleged to have stolen.