Even if there were a constitutional ban on racial discrimination, racism would remain entrenched

It is impossible for race to be substantively or actually removed from the Constitution when it is built on it.

"Completing" the Constitutional project through "recognition" is in fact a continuation of assimilation.

Maria Giannacopoulos, a lecturer and researcher in Socio-Legal Studies believes that Frank Brennan's recently published conservative position on Constitution reform, leaves us with a flawed structure and giving us only superficial changes.

Even though the problem Brennan seeks to address is racism, Brennan argues for leaving a racist structure undisturbed. Giannacopoulos believes he may have done this, because he does not view the Constitution through the larger lens of colonisation.

Maria Giannacopoulos The Conversation 27 May 2015

This article is a response to the issues raised in Frank Brennan: the case for modest constitutional change, published on The Conversation.

The Australian Constitution is a document that imposes and maintains a colonial infrastructure through which Australia's profound debt crisis continues to be denied. By presenting the Constitution as "a fairly prosaic, legalistic document" in his recent article on The Conversation, Frank Brennan minimises the role played by the Constitution in establishing colonial law and colonial political structures when founding modern Australia.

Removing reference to 'race' does not change a racist Constitution

Brennan, an influential legal commentator on race issues, suggests that "Australians are increasingly aware and dissatisfied" that the Constitution does not mention Aboriginal people. He believes that Tony Abbott's suggestion that recognition of Aboriginal people would "complete" rather than "change" the Constitution would be acceptable to the Australian people because it would not bring about any "substantive" changes.

Decoding the legal-speak, Brennan's argument is that this move for change will be successful because no "real" changes will result.

In my view, as a lecturer and researcher in Socio-Legal Studies, that is a conservative position: it seeks to leave a flawed structure in place by undertaking only superficial changes.

Even though the problem Brennan seeks to address is racism, Brennan argues for leaving a racist structure undisturbed. He does this, I imagine, because he does not view the Constitution through the larger lens of colonisation.

Why the Constitution is more than an 'attachment to an Act of British Parliament'

Brennan minimises the significance of the Constitution by saying that it is "simply an attachment to an Act of the British Parliament". That is true. In 1900 the British Parliament passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which came into force on January 1, 1901. But the effect of this statute cannot be underestimated.

Vital information has been left out of this legal framing of the story.

How did Britain come to hold such power over the colony? How can a law which continues to have such far-reaching implications be reduced to an attachment? The Constitution, as Brennan outlines "sets out the basic structure of the Australian federation". The separation of powers doctrine is established by setting out the relationships between the Parliament, Executive and Judiciary.

But what is displaced when this power structure is installed?

Frontier colonial violence, dispossession amounting to denial of Aboriginal laws and sovereignty, are removed from view. The "basic structure of Australian federation" divides and separates power while maintaining exclusive law-making power over the nation. Whether the states, the judiciary, the executive or parliament make law, it is still an imposed law.

By leaving out the violent foundations of Australian law the Constitution appears innocent. But questions remain. Legal scholar Irene Watson asked in 2012:

by what lawful authority do you come to our lands? What authorises your efforts to dispossess us?

Leaving out these questions allows the Constitution to seem innocent and as an appropriate starting point for deciding on what is racist.

It is the hijacking of the space for law-making and sovereignty that makes the Constitution deeply racist. It whitewashes over the fact that Australia was, in activist Ruth Gilbert's words, a:

continent owned and carefully managed for millennia by Aboriginal people […] who had a highly evolved system of law and governance.

A violent foundation and the displacement of Aboriginal laws are the bigger issues on which the Constitution should be held to account.

'Recognition' is not what it seems

Brennan, a Jesuit priest and Professor of Law, advocates for "modest constitutional change".

This would include:

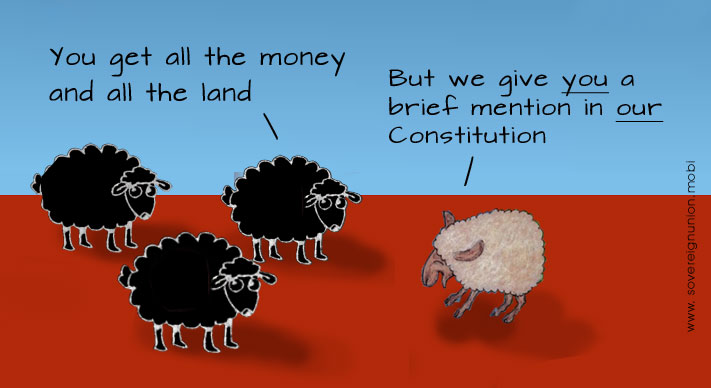

a factual acknowledgement of Aboriginal history, culture, languages and land rights; deleting the racially discriminatory section 25; and amending section 51(26) to allow the Commonwealth Parliament to make laws with respect to the distinctive Aboriginal matters listed in the acknowledgement.

Brennan does not believe in a constitutional ban on racial discrimination as this would place the "our constitutional arrangements out of kilter". If this last point appears controversial, it is an illusion.

Even if there were a constitutional ban on racial discrimination, racism would remain entrenched.

The suggestion that "modest change" is required amounts to no change at all if the problem being addressed is racism. Once the Constitution is seen in the context in which it was born, it becomes clear that to continue to focus on whether race should be removed is to miss the point.

It is impossible for race to be substantively or actually removed from the Constitution when it is built on it.

"Completing" the Constitutional project through "recognition" is in fact a continuation of assimilation.

"Recognition" retains the central place of colonial law by benevolently mentioning Aboriginal culture and history while remaining silent on the question of surviving Aboriginal laws and self-determination.

The Australian Constitution is a nation-founding document and since it is a British attachment it founds a replica British nation on Aboriginal lands. This is the broader way in which the Constitution is implicated with racism.

Seeing the foundational violence of the Constitution is a more challenging proposition but it needs to happen if we are to own up to the profound debts owed to Aboriginal peoples who have not - in the words of Ruth Gilbert - "been compensated for the theft of their country".

Maria Giannacopoulos is a Lecturer in Socio-Legal Studies at Flinders University