Fighting for land nothing new for First Nations elder

Murra Wurra Paakintji elder Dorothy Lawson says her grandparent's rights as "squatters" were over-looked when authorities built a water storage basin at Lake Victoria in 1922.

Deb Banks and Damien Hooper

ABC Mildura Swan Hill 7 June 2013

An Aboriginal elder from far western New South Wales is threatening to take a case to the high court to prove her ownership of Lake Victoria.

The lake supplies parts of South Australia with drinking water.

Dorothy Lawson's family has been in the area for thousands of years, but will argue a legal technicality, under a law known as Nullum Tempus.

That means they had rights as squatters on the land.

In Dorothy Lawson's mind, however, the idea of having the right to squat on her country is nothing new.

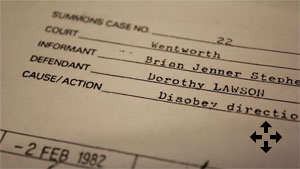

In 1981 she stood in front of a bulldozer threatening to knock her humpy down, and defeated an eviction notice served on her by the Wentworth Shire Council for squatting on Crown reserve.

Detailed records of the case are difficult to find, but she remembers it clearly.

"Bob Blair - he was an Aboriginal barrister - but he's passed now, unfortunately. He came down, he took the case up for me with Eric Wilson, a solicitor that was working in I think with the land trust at the time," Mrs Lawson recalls.

"And there was a letter sent from the Judge Pat O'Shane at the time congratulating me.

"I didn't get a big head out of it I wanted to take them on because it was so many times that they knocked my little camp down," she says.

"When you're born in a country and you only know one country I don't know Queensland, I've never ever been outside of my father's country other than Cootamundra (Home for Aboriginal Girls)," she says.

Mrs Lawson recalls several occasions when she was forced to move home to make way for development on the land where she lived.

"I saw them develop and I asked the question on several occasions, what's going on? Oh they're building a block or a person leased or bought a block there," she says.

Mrs Lawson says it was the final straw when the bulldozers came for the seventh time to make way for a pony club.

"So I said alright, you can have your pony club, you've got to have me too with the pony here.

"I was fighting my right. Alright so if they ask me if I squatted, I'm one of the early squatters so I'm going to fight, you know this is my part of the country.

"I came home to it, I was taken away from it.

"I'm not going to go away without a fight but I didn't think I'd ever come home to a fight. I thought I'd come home to something that I was provided that was handed to me," she says.

Nullum tempus occurrit regi ("no time runs against the king"), sometimes abbreviated nullum tempus, is a common law doctrine originally expressed by Bracton in his De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliae in the 1250s. It states that the crown is not subject to statute of limitations.[1] This means that the crown can proceed with actions that would be barred if brought by an individual due to the passage of time. The doctrine is still in force in common law systems today, in a republic it is often referred to as nullum tempus occurrit reipublicae.[2] - Wikipedia

Were Aborigines Australia's first 'squatters'?

Deb Banks ABC Local 6 June 2013

An Indigenous family from the Western Division of New South Wales is on its way to finding out, and say they'll take the question to the High Court, if necessary. Murra Wurra Paakintji elder Dorothy Lawson says her grandparent's rights as "squatters" were over-looked when authorities built a water storage basin at Lake Victoria in 1922.

She and her son Philip are seeking damages from SA Water for the taking of their family's land and waters, and for pain and suffering due to desecration of the area - classed as one of the largest pre-industrial burial sites in the world.

If SA Water rejects the claim, the question will be contested in the courts.

The Lawson claim will contest, the first legally recognised squatter in Australia was a Mr Love.

Little is known about this man, or his case, but it was referred to in a land rights decision by the Canadian Supreme Court in 1974.

In the 1898 case "Attorney General for New South Wales versus Love", the Privy Council found he had squatted for the required 60 years on Crown 'wasteland' and in so doing, could not be evicted.

Earlier that century, an ambitious young lawyer who'd go on to head up the Pastoralists' Association in the Legislative Council - Charles Wentworth - unsuccessfully tried to argue "squatters rights".

His client - a Mr Steele - was refused his right of possessory title, because by 1839 he'd not squatted on the land for the required 60 years.

If Mrs Lawson's claim goes to court it will be the first time this law - known as Nullum Tempus - has been tested by an indigenous person, and only the second time since Mr Love in 1898.

In her mind, however, the idea of having the right to squat on her country is nothing new.

In 1981 she stood in front of a bulldozer threatening to knock her humpy down, and defeated an eviction notice served on her by the Wentworth Shire Council for squatting on Crown reserve.

Once again, detailed records of the case are difficult to find, but she remembers it clearly.

"When I came out of court, he kissed me on the forehead and said, 'Good.'.

"What is so good for having to have to fight for what you believe is right? You know, I didn't get a big head out of it. I wanted to take them on because it was so many times they that they knocked my little camp down," she says.

Claiming "squatters" rights, Mrs Lawson's case will by-pass the Native Title Act as it deals with ownership after 1788. There is no native title claim on Lake Victoria.

Mrs Lawson says of course she supports the right of Aboriginal people to their lands, but the Native Title Act has done her people no favours.

"No I won that case in 1981 and two years after that in 1983 they decided to come in with the lands right act. I've got nothing to do with that land rights act. To me that's against my belief of owning, or the ownership (of those) traditionally affiliated with the area.

"We took out a native title, that's where the land council came in and got involved in that and took it away from the traditional owners that did the native title in the first place. It's all over like dog's breakfast," she says.

Even after her court win, Mrs Lawson struggled to find a permanent home on her traditional lands.

She says her first home was sold out from under her, her second home burnt down, and when it was rebuilt, she wasn't given the option of returning to it.

"I was out of home. I had to get a house in Broken Hill. A couple of my family members came up and said, 'You don't belong here, you belong down there.', 'What? To be pushed around again?, alright I'm coming back.

"I've always had in mind I'm coming back, you'll never, ever get rid of me I said. Got a transfer back off that house then, and it didn't happen in the Wentworth Shire, it happened here in Mildura.

"I guess I'm one of those proud ladies that my grandmother and them, had the staunch you know, and that's how I am today, and I'll always be like that. I can never be bought out, you know. I'm only asking for my father's inheritance," she says.

Mrs Lawson was reunited with her grandmother for the last two years of her life, before she died in 1956 aged 104.

"My grand-mother said that was her part of the country. She was born and bred on it. She told us beforehand before I was taken away and she's told me when I come back from the home, I want to go back to my place. My Home," she says.

Mrs Lawson's claim contends that in 1922 her grandparents were never compensated for the loss of their land when South Australia took ownership of Lake Victoria from New South Wales.

"They mustered them all out, that's where they brought them in. There is a Jail there on the Rufus River.

"They got out with what little families they had. What my grandmother said it was most of her family that was slaughtered there and that's why they didn't want to leave there.

"She always wanted to go back to Nulla station and we said no you can't now Nan because somebody else owns it. But she always believed that it was hers. That it was given, it was their inheritance you know," she says.

Lake Victoria's purpose today is to provide water security for South Australia, and while owned by SA Water, is governed by New South Wales laws.

Queensland and Victoria were also still being governed by New South Wales laws prior to 1848.

Did Nullum Tempus exist in 1848? Did landholders like Mr Love who'd been squatting on "wastelands" of the Crown gain ownership after 60 years?

Depending on how the courts choose to answer the question - Mrs Lawson's case has the potential to hold up native title hearings across the country, and have the courts reviewing past decisions.

Mrs Lawson sees it only one way.

"I want to claim what's rightfully mine and that's the inheritance of my father what was handed down from my grandmother.

"My great-grandparents and that's exactly where I've headed yes. It'd be a court case. I'm not going to back down, and I'm going to see it through with the last breath in my body. I'm not going to back down for nobody," she says.

SA Water has confirmed it has received a Notice of claim and Abstract from Dorothy and Phillip Lawson, adding - as the matter is currently being reviewed and is the subject of legal discussions, it would not be appropriate to comment further at this stage.

ABC PM Radio Transcript

Possible Indigenous claim to Lake Victoria

ABC PM - 6 June 2013

ASHLEY HALL: An Aboriginal elder from far western New South Wales is threatening to take High Court action to prove her ownership of Lake Victoria, near the border with South Australia.

Dorothy Lawson's family has been in the area for thousands of years, and she hopes to argue that under a legal technicality they have rights as squatters over the land.

Deb Banks prepared this report.

(sound of Dorothy Lawson singing)

DEB BANKS: In far western New South Wales Dorothy Lawson remembers her ancestors' traditions.

DOROTHY LAWSON: (singing) One for the money, lay down in the water...

DEB BANKS: She's an elder in the Murra Wurra Paakantji tribe, who've lived in this part of the world for thousands of years.

Before European settlement the land was very different.

DOROTHY LAWSON: It was never a lake. Only on rainy days we used to have a little water there, but what was once there, they destroyed.

DEB BANKS: She's talking about Lake Victoria. Its purpose today is to provide water security for South Australia, and while owned by SA Water, it's governed by New South Wales laws.

But Lake Victoria remains an important cultural site for Mrs Lawson's family and is one of the largest pre-industrial cemeteries in the world.

DOROTHY LAWSON: I don't know whether it was guilt that provided it, you know, guilt to run water on a burial site where they did the massacre, you know, there at Lake Victoria.

DEB BANKS: Because of the connection with the area, Dorothy Lawson hopes to prove her ownership of the lake and surrounding lands.

Mrs Lawson's claim contends that in 1922 her grandparents were never compensated for the loss of their land when South Australia took ownership of the lake from New South Wales.

DOROTHY LAWSON: They mustered 'em all out. That's where they brought 'em in. There was a jail there you know? On the Rufus River. They got out with what little families they had.

What my grandmother said, it was most of her family that were slaughtered there, and that's why they didn't want to leave then, because she always wanted to go back to Nulla Station.

And we said, "No, you can't now Nan because somebody else owns it." But she always believed that it was hers. That it was given, that it was their inheritance, you know.

DEB BANKS: Her grandparents occupied the land without legal ownership. They were effectively squatting.

Now Dorothy Lawson intends to use a little known law to claim those squatting rights - nullum tempus.

If it goes to the High Court it will be the first time this land title law has been tested by an Indigenous Australian.

DOROTHY LAWSON: I want to claim what's rightfully mine and that's the inheritance of my father, what was handed down from my grandmother, my great-grandparents, and that's exactly where I've headed, yes. It'd be a court case.

I'm not going to back down. I've come this far and I'm going to see it through until the last breath in my body. I'm not going to back down for nobody.

DEB BANKS: On behalf of her family, Mrs Lawson is asking for a share in a family inheritance of 2,750 pounds.

DOROTHY LAWSON: You can't pass-on unless you leave something to your children. And there is something there that my grandmother left to my father, my great-grandparents left to my granny. All I want is my inheritance through my father.

DEB BANKS: SA Water has confirmed it's received a Notice of Claim from Dorothy and Phillip Lawson, but is refusing to comment.

ASHLEY HALL: Deb Banks with that report from Mildura in western Victoria.