Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) elders share sacred songline

preserving one of Central Australia's oldest intact songlines called the Ngintaka, or Perentie Lizard, dreaming.

Karen Ashford SBS News 27 February 2014

| Transcript from World News Radio |

A painstaking project to capture one of Aboriginal Australia's most important creation stories is set to be unveiled in Adelaide.

The endeavour has overcome controversy to preserve one of Central Australia's oldest intact songlines called the Ngintaka, or Perentie Lizard, dreaming.

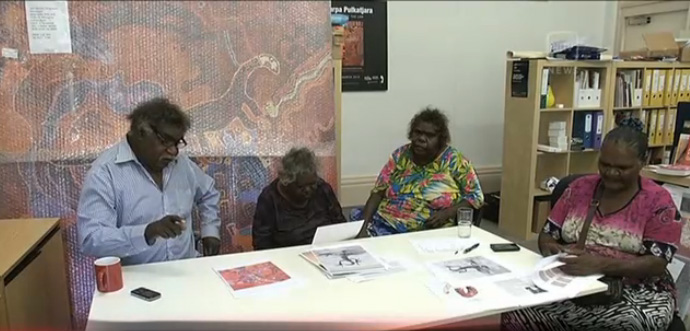

Canvases sheathed in bubble wrap fill the cramped offices of Ananguku Arts, where a group of APY* elders is busy selecting the final works for one of Australia's most ambitious exhibitions.

The paintings showcase Ngintaka - the perenti lizard man - a mystical being at the heart of a creation story mapping outback lands.

His is a tale of theft, deceit, and vengeance, involving Ngintaka stealing a grinding stone and fleeing, changing the landscape along the way and eventually being transformed himself into a mountain.

Generations of Aboriginal people known as Anangu have learned the Ngintaka tale - and how he created food sources and waterholes still found today - through a musical story called a songline.

Margaret Richards is an elder who began learning the songline and its associated elements as a child.

"Dad told me a story about the perentie who stole the grinding stone from Wallatina. Also, I paint the perentie story on a canvas and learnt to sing and dance that story."

The oral tradition of Anangu has carried this story for centuries.

But elders like Robert Stevens are worried their lore called tjurkurpa is in jeopardy.

"For the young kids, young people, young generations to continue on. Otherwise if they don't have tjurkurpa they really don't have anything, they are lost. When someone goes there and asks them what dreaming is yours? They don't know, they don't have tjurkurpa. That's what will happen one day."

Anangu have increasingly seen their children seduced by modern technology, and fear their culture could be drowned out by Westernised consumer culture.

They approached experts about harnessing those new technologies to their advantage, to protect their dreaming stories.

Australian National University anthropologist Diana James has been assisting Anangu to commit stories, songs, dance and art to the digital realm as a defence against cultural decay.

"The reason why Anangu in 1988 decided to teach this story publicly and settle on a public version that could be taught to nonindigenous people as well was because they realised with the intrusion of Western culture onto their lands - television, radio, DVDs, games and players - that there young people were getting more and more involved in modern media really, so they were keen that their stories be recorded and be accessible through modern media."

Diana James says the songline project gives insights into one of the world's oldest continuous cultures.

"The knowledge of the seeds, the importance of these grasses through the Lands, the importance of waterholes for people travelling through the desert, the song and how it marks the way through the Everard, Musgrave and Mann ranges is profound as a teaching tool for Anangu for young children and also for nonindigenous people to understand the significance of these foundational cultural roots of Australia."

Elder Inawinytji Williamson says the Ngintaka story is one of the most important to Anangu and sharing it with others will foster understanding of Aboriginal culture.

"It's important and a big story and also song. This is a big Inma or ceremony from a long time ago for our old people and songs too. It's good and interesting for us and grandchildren to learn the story and the songs. It's also very important for all the people."

However, it hasn't been entirely smooth.

Elder Yami Lester doesn't think the songline should be shared with outsiders and is opposed to it being anything other than an oral tradition.

Mr Lester says there's concern the project aims to profit from sacred beliefs.

"A lot of people not happy that they're pushing it for money. It's selling Aboriginal culture and our creation stories for money now. For long time Aboriginal people's stories have been handed down by word of mouth, always, for early days but because of dollars the mighty dollars, they got to make a film and tell stories."

Ms James says she took Mr Lester's concerns seriously and paused the project to again consult communities, cultural custodians, artists, elders, and the Lands Executive.

She says Anangu have maintained full control over all aspects of the songline preservation project, including what is recorded and in what form, and also how it can be used.

Those directly involved in the project were paid recommended rates as artists and cultural consultants; artists already sell their artworks through community art centres on the APY Lands.

Ms James says the meetings confirmed communities' determination to see the songline story preserved and shared using modern methods.

"We had unanimous support from all those communities, and so I'm confident that though some people may have a difference of opinion about whether it's appropriate to write down oral traditional knowledge, there was overwhelming support from these communities and the request from senior traditional owners like Robert Stevens and David Miller to have this recorded for their children."

Robert Stevens isn't just a senior traditional owner.

He was born with a hand shaped like the perentie's claw, making him an incarnation of the Ngintaka's spirit.

Mr Stevens says he has been guided by the Ngintaka throughout the preservation project and thinks sharing the songline will keep culture strong.

"On the lands we're lucky you know, we got our children supporting the tjurkurpa you know. We got to show the other people too, you know. And it's really working well."

His wife Fairy Stevens accepts that some people on the lands might disagree with the project but those closest to the songline believe that it is important to preserve the story before it becomes lost to the modern world.

"This story is strong. Our culture, if we lose it we feel weak and forget our story and songs. Yes, some people don't want to share the story and songs with anyone, but we want everyone to share the story and songs. We know a lot, but also we want non-Anangu to learn and whitefellas. We want to talk to them about the story and the songs."

Diana James says it's the desire to share knowledge that makes this project special.

"This songline obviously is one of many and in all cultures and all languages of all the Aboriginal nations around Australia they hold this knowledge very strongly and have passed it on for generations through song. This is not the only recording project that's going on around Australia, but the fact that Anangu have chosen to share it is an opportunity for nonindigenous Australians to enter into that world and understand the depth and breadth of Aboriginal knowledge and their reasons for so strongly talking about the importance of cultural knowledge in caring for country. So I think it has the potential to transform Australian perception about the value and significance of indigenous knowledge."

The South Australian museum will host the Ngintaka project launch in late March, when Anangu will reveal a rich slice of their history to the world.

(APY: Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yunkunytjatjara traditional Aboriginal lands in far north-west SA)