The Freedom Fighters - Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheenner and Truganini

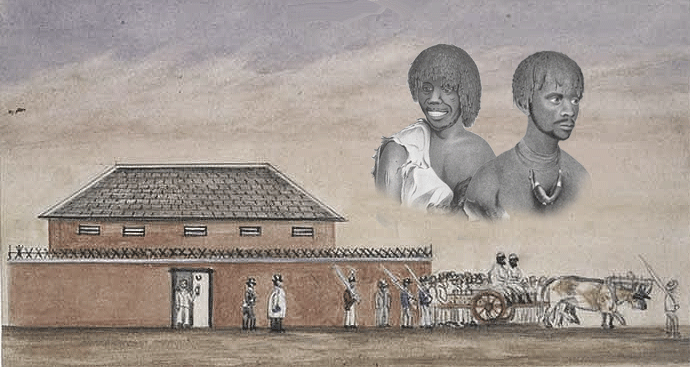

The hanging of the Freedom Fighters - Background image: 'The first execution' Painted in 1875 by WFE Liardet. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, Left inset: Portrait of Tunnerminnerwait by Thomas Bock c1831-1835, Right inset: Portrait of Maulboyheener by Thomas Bock c1831-1835,

The hanging of the Freedom Fighters - Background image: 'The first execution' Painted in 1875 by WFE Liardet. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, Left inset: Portrait of Tunnerminnerwait by Thomas Bock c1831-1835, Right inset: Portrait of Maulboyheener by Thomas Bock c1831-1835, Dr. Joseph Toscano 13 December 2013

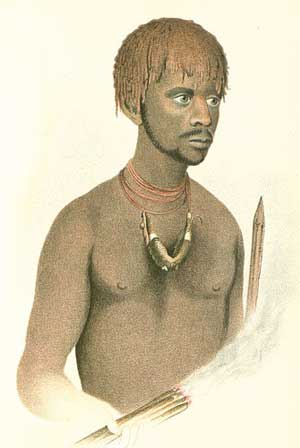

Portrait of Tunnerminnerwait

by Thomas Bock

1831 - 1835

portrait of Maulboyheener

by Thomas Bock

1831 - 1835

Portrait of Truganini

George Robinson

Chief Protector of Aborigines

It's tragic the names of Native American freedom fighters Geronimo and Sitting Bull and Native American tribes like the Apache, Sioux, Mohawk and Mohican strike a chord with Australians and appear in the Macquarie Dictionary - Australia's National Dictionary, while the names of Australian Indigenous freedom fighters Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner draw a blank with Australians and the Macquarie Dictionary.

The story of the Indigenous freedom fighters Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheenner, Pyterruner, Truganini and Planobeena is a story that should be as familiar to Australians as the North American Native American struggle against European colonisation is.

Their story, a tale of passion, love, treachery, murder, vengeance, resistance, freedom and death. It is a story that is as important today as when it occurred 170 years ago.

At 8:00am on Tuesday 20th January 1842, over 5,000 people, a quarter of Victoria's white population, gathered at what was then the outskirts of Melbourne, a small rise opposite today's Melbourne City Baths near the corner of Bowen and Franklin St, Melbourne. The crowd in a carnival mood had come to see the public execution of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner - the first two people executed in Victoria.

Tunnerminnerwait, the son of Keeghernewboyheenner, was born on Robbins Island, Tasmania in 1812. He was also known as Peevay, Napolean, Jack of Cape Grim and Tunninerpareway. Maulboyheenner came from one of the inland tribes that had lived on the Ben Lomond highlands in Tasmania. He was also known as Robert Smallboy, Jemmy, Timmy, Tinney Jimmy, Robert of Ben Lomond and Bob.

Both young men came into contact with George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Tasmania in 1830. Robinson was attempting to round up the remnants of the free tribes of Tasmania and resettle them on an island off the North Coast to prevent them from being "exterminated". The 33 year old war against the European colonisers was over by October 1835 when around 350 Tasmanian Aborigines who had survived the holocaust were transferred to Flinders Island under the care of Robinson. Three quarters of those who were transferred to Flinders Island died within two years of their arrival.

George Augustus Robinson had big plans for himself and 'his' Aborigines. Even before John Batman set up his illegal settlement at Port Phillip Bay, the Governor of Van Diemen's Land - Sir George Arthur, wrote on the 27th of September 1835 to the Colonial office in England informing them that George Robinson was willing to take 'his' Aborigines to the newly established settlement at Portland Bay on the Australian mainland to "open a friendly communication with the natives there".

George Robinson finally got his wish on the 12th December 1838 when he was appointed Chief Protector of Aborigines at Port Phillip. By then the Tasmanian Aboriginal population on Flinders Island had slumped to 89. Robinson and 16 of the 89 Tasmanian Aborigines on Flinders Island arrived at Port Phillip in January 1839.

Even a man as hardened as Robinson was shocked by "the disease, destitution and wretchedness" displayed by the Port Phillip Aborigines living on the outskirts of Melbourne. The Chief Protector had four Assistant Protectors appointed to help him "ameliorate the lot of local tribes in the face of introduced disease, the ravages of alcohol and tribal warfare, interracial massacres and poisonings".

The colonisation of Victoria had been a brutal affair despite the presence of Aboriginal Protectors. In June 1838 a party of 28 Aborigines, mainly women and children, were tied up and hacked to pieces with swords at Myall Creek, north of Sydney.

Pressure from the Anti-Slavery Society in England and the Aborigines Protection Society in London led to the hanging of the seven assigned convicts responsible for the massacre in late 1838. In May 1839 Gipps, the New South Wales Governor who was also responsible for the newly established Port Phillip settlement, declared in the government gazette he wanted to bring the settlers and the Aborigines to "equal and indiscriminate justice". These events caused consternation among the Port Phillip settlers.

'Robinson's first interview with Timmy' (One of Maulboyheenner's given names)

Detail of 'The Conciliation', an 1840 oil painting by Benjamin Duterrau 1767-1851

(Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, AG 79) Enlargement available here

The open warfare that had been occurring between Aborigines and squatters in the Port Phillip region and the rest of Victoria became a secret covert war of destruction almost overnight. Nobody talked about what was happening; Aborigines with gunshot wounds were dismembered and burnt. In August 1840 Superintendent LaTrobe, concerned about Robinson's capacity to deal with the local aborigines, asked the New South Wales Governor to relieve Robinson of the responsibility for the Van Diemen's Land natives. Robinson was officially relieved of responsibility of their care on the 2nd October 1840.

On the pretence they were going to join the Assistant Protectors camp at Westernport - Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheenner, Pyterruner, Truganini and Planobeena, 5 of the original party of 16 vanished into the Westernport bush in August 1841. Planobeena was Tunnerminnerwait's wife, Maulboyheenner was involved in a relationship with Truganini. William Thomas, one of the Assistant Protector's oldest son, wrote in his private journal "He (Jack of Cape Grim) talked about what they had suffered at the hands of the white man, how many of their tribe had been slain, how they had been hunted down in Tasmania - now was a time for revenge, they were not cooped up in an Island (Flinders), they had unlimited bush to roam over at will".

This little band of two men and three women were familiar with the white man's ways. They knew how to use firearms; they knew how to survive in the bush. It was six years since Melbourne was formed - over 8,000 whites lived in the new town. The local Aborigines had, to a large degree, been subdued and posed little threat to the settlers in Melbourne.

In October 1841 fear and trepidation swept through the town as the exploits of the Tasmanian blacks became known. Many of the settlers had come to Melbourne from Tasmania. They were aghast their old foes - the Tasmanian Aborigines who had only been defeated after a 33 year brutal and bitter struggle were mounting a determined resistance to white settlement on the outskirts of Melbourne in Dandenong and the Westernport region.

By the 30th October 1841 the police party pursuing the five freedom fighters had swelled to 18 men on horseback and 6 on foot. The Aborigines laid down the gauntlet to the pursuing police party leaving messages at a station they had robbed, they would fight to the last man and woman.

Walking up to thirty miles a day to evade capture, they continued to rob and burn stations forcing the squatters back to Melbourne. They stole firearms, sugar, flour and tea. Considering they were trying to move quickly through the bush to evade capture, it is highly likely they were collecting firearms to distribute to the local Aborigines. In the many raids they carried out, they never harmed women and children. The men that were shot in the raids were shot in the heat of the battle.

Two whalers, William Cook and "Yankee" died when they stumbled into an ambush the Aborigines had prepared for pursuing squatters. They burned down the huts they raided to drive the squatters back to Melbourne. At daybreak on Saturday 20th November 1841 the five freedom fighters' luck finally ran out. A posse consisting of 29 soldiers, police and squatters mounted on horseback and 8 armed black trackers managed to sneak up to within two metres of the sleeping Aborigines before the Aborigines' dogs rushed at the posse.

Miraculously only one of the women received a superficial head wound despite over forty shots being fired at the sleeping Aborigines' heads.

The five resistance fighters were put on trial for the murder of the whalers on the 20th December 1841. They appeared before Judge Willis, the settlement's first Supreme Court Judge, a man described by Governor Gipps in 1843 as - "an apologist for the cruellest practises by some of the least respectable of the settlers on the Aborigines". Judge Willis had the distinction of being removed from his first appointment to the Upper Canadian Court in 1827 by the British Colonial Office. His appointment to the British Guiana Court came to an abrupt end when the community refused to take him back after he had taken twelve months sick leave in England.

In 1837 he was sent to sit on the Supreme Court in Sydney. When a decision was made to open a supreme Court at Port Phillip by Governor Gipps to save the colony the cost of sending capital cases to Sydney for trial. Governor Gipps took the opportunity to transfer the judge "who some people think cracked", to Melbourne.

Redmond Barry

Defence Counsel for Aboriginals

In 1841, Aborigines were not equal in the eyes of the law. They could not testify or lay charges in courts. The only way they could achieve even a modicum of justice was for a white witness to testify on their behalf. Considering the crimes against humanity that were being perpetrated against Aborigines were conducted in an undeclared frontier war, where those squatters doing the killing were the only white witnesses, the ruling against Aboriginal evidence ensured that crimes committed against Aborigines never made it to the colonial courts. Despite these legal limitations, Redmond Barry, the Defence Counsel for Aboriginals in the Port Phillip region mounted a spirited defence on their behalf.

Barry highlighted the evidence was largely circumstantial and the confessions by Truganini and Maulboyheenner should not be accepted because they were from people "in a state of terror". He attempted to win the jury's sympathy by highlighting what every settler in the colony knew, but refused to acknowledge, "we must remember the course of their destruction, at first insidious and private, then open and declared, which eventually swept a numerous nation off the face of their native country and transported the remnant to a foreign to them, distant shore".

Barry argued against the validity of the court proceedings highlighting the Aboriginal population had not entered into a treaty with the colonisers. If the name Redmond Barry seems familiar, the young Irish Aboriginal Defence Counsel is the same Redmond Barry who as a Victorian Supreme Court Judge presided over Ned Kelly's trial almost 40 years later in 1880.

Later that same evening the jury took just 30 minutes to reach a verdict. They found Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner guilty of murder and acquitted the three women Planobeena, Pyterruner and Truganini of all charges. The jury recommended mercy for the men "on account of general good character and the peculiar circumstances under which they were placed".

The next morning the 5 were returned to court for sentencing. Judge Willis discharged the three women into Robinson's care and then addressed the two men, "By the confessions of Bob (Maulboyheenner) and the statements of Truganini, there can be no doubt of your guilt the punishment that awaits you is not one of vengeance but of terror ... you will be taken to the place of execution and be hanged by the neck until dead".

As expected the local press welcomed the sentence. The Port Phillip Gazette highlighted the Aboriginal people's "ineradicable love of destruction and as a consequence, the imperative necessity of coercion in their management". On Tuesday the 20th January 1842 the Port Phillip Herald reported: "an immense crowd ... between 4,000 and 5,000 people, the greater part of whom were women and children. From the laughing and merry faces which were assembled .. the scene resembled more the appearance of the racecourse than a scene of death. The walls and body of the new goal were literally packed with spectators awaiting the awful scene as if it were a bull bait or a prize ring". The Port Phillip Gazette reported the condemned men's arrival was met "in explosions of up roarious merriment".

'The first execution' Painted in 1875 by WFE Liardet. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria

As the Preacher uttered the key words, "in the midst of life we are in death", the executioner and his assistant pulled the rope. The 'drop' only descended half way and a terrible scene followed "thus the two poor wretches got jumbled and twisted and writhed convulsively in a manner that horrified even the most hardened". The bodies were cut down from their nooses after the regulation hour. They were stripped of their clothes and transported to be buried in unconsecrated ground just north of the eastern end of the wall that currently divides Melbourne's Queen Victoria Market.

Dr. Joseph Toscano was one of the founders of the 'Freedom Fighters Remembrance Day'. In 2005 Dr Joseph Toscano was motivated by Jan Roberts account if the Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner executions and organised a commemoration on the anniversary in 2006 at the site of the execution. The commemorations have continued every year since then.

Since then Clare Land studied this period of Melbourne's history extensively and has produced a book: Decolonizing Solidarity