Court ruling gives NSW police 'The right to silence'

NSW Police Association says court ruling in Errol Baff case confirms officers' right to silence

Ellesa Throwden ABC News

The NSW Police Association has welcomed a court ruling that allowed a policeman to avoid answering questions about the shooting of a woman on the state's mid-north coast.

In May 2011, Constable Errol Baff fired his gun and injured a woman at Coffs Harbour on the New South Wales mid-north coast.

An investigation was launched, but Constable Baff refused to answer questions citing the common law privilege against self-incrimination.

This week the NSW Supreme Court upheld that privilege, ruling against the Commissioner of Police.

The association's president, Scott Webber, says it was a test case and a win for all police officers.

"What this means is that police officers have the same protections as everyone else," he said.

"The decision could also have implications for critical incident investigations in the future.

"That is, they cannot be forced to answer questions when they have allegedly committed a criminal offence."

Cops' right to silence in NSW courts

Ray Jackson, President

Indigenous Social Justice Association

Ray Jackson 1 September 2013

On 20 March, 2013 we were advised by the NSW O'Farrell government, but especially the attorney-general, Greg Smith, and the police minister, Mike Gallacher, that the innate right to find protection in enacting our right to silence when being questioned by police was to be put into legal oblivion. As the following article by associate professor David Hamer and professor Gary Edmond on this change to the NSW law has allowed for several pitfalls that they explain. Their views, of course, differ greatly to the points made by the government.

The law against incriminating one's self against criminal or civil charges is very well known and has been around for some time. I believe it should be an inalienable human right that should not be taken away by governments so easily.

But the concern that I have arises not just from that human right being so easily removed but from an event that happened to a Coffs Harbour, NSW police officer in May, 2011 when during an altercation with a woman his firearm was fired and the woman was grievously injured. The officers involved in that incident were all interviewed by senior police officers but the constable directly involved refused to be interviewed by his seniors. And why? Because if he did so he could possibly face either criminal or disciplinary charges. In a full legal sense constable Eric Baff is easily able to retain his right to silence.

The immediate question that springs to one's mind is whether police are to be, again, treated differently when they become involved in critical events such as police brutality, death in custody events or other actions needing to be independently investigated.

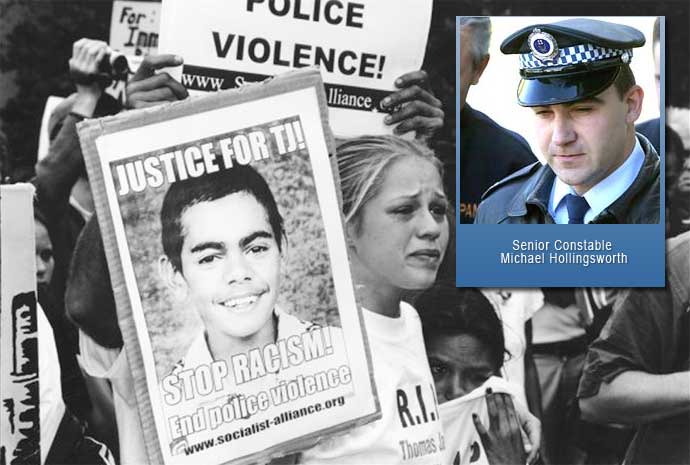

During the coronial inquest of the police initiated death of 17 year old TJ Hickey in February, 2004 the four police officers were all interviewed by the police investigating the concerns raised by the police chase that led to his death. Most readers know that the Hickey family, ISJA and others found fault with both the police investigation and the actions of the state coroner involved at that time and we are continuing to action our call to re-investigate the issues by an independent investigative team and to have a new coronial inquest that allows all witnesses and evidence to be called to come to the truth and justice of how and why young TJ died.

During the original inquest the demeanour and veracity of the four police left much to be desired, a point made by both the state coroner and his legal assistant. when it came, however, for constable Michael Hollingsworth to take the stand to give his evidence it quickly deteriorated to a very sick farce. After giving his name and rank, his number and his station he then, on advice to be sure, announced that he would not answer any further questions as it may incriminate him and possibly lead to charges from his employer, the police commissioner.

Such a call is not unprecedented and is commonly used in coroners courts by serving police officers and others. The coroner can easily however get around this call for the right of silence by invoking his powers under the NSW Coroners Act 2009, s61. This power allows the coroner to instruct the witness to answer all questions put and the coroner would issue him/her a certificate stating that any evidence given cannot or would not be used in any other court of law so long as the evidence proved to be true. Normally this is enough to proceed matters accordingly.

For a state coroner who in his opening remarks seriously opined that he was there to adjudge the evidence to assist him to come to the truth of the circumstances of the death of young TJ, he amazingly allowed Hollingsworth to walk. That this was a fabricated pre-agreed action by those legal entities involved was re-enforced when the Carr government appointed legal team to the Hickey family sat on their legal hands. Nothing! No strong protest whatsoever.

Hollingsworth needs to be recalled, as do his fellow officers, to face a vigorous and proper examination of the facts occurring on that 2004 valentines day. Nothing less is acceptable and we will continue to fight for it.

To return to constable Babb, we are possibly watching another element of escape by police officers from facing charges for their brutality against members of the public. If police are given yet another escape clause then that just tightens the already limited possibilities of forcing police to pay the legal penalty for their criminal acts as do we members of that public.

Other aspects within the news article and the decision by justice Christine Adamson, that I have provided the link to, are also of great concern as to the in-house legal procedures when police are involved.

Constable Babb made no statement whatsoever and yet we are informed that in may last year the DPP had already stated that there is "insufficient evidence" to make any charges against Babb. Of course there is insufficient evidence; Babb has not said anything so the insufficiency is self evident. But instead of awaiting the outcome of the current stand-off the DPP has washed their collective hands on the issue. Where is the justice in that!

Babb declined to be interviewed for a critical incident interview so he was then told by the senior officers that as there were no DPP charges to be laid against him he should at least be available for a "non-criminal interview." Babb, apparently not fully trusting his senior officers, continued to decline. And so the sorry state of affairs continue there downhill race.

fkj

Ray Jackson

President, Indigenous Social Justice Association

Email: isja01@internode.on.net

Mobile: 0450 651 063

Landline: 02 9318 0947

Address: 1303/200 Pitt Street, Waterloo 2017

Website: www.isja.org.au

When you say nothing at all: NSW and the right to silence

The Conversation 22 March 2013

by David Hamer, Associate Professor of Evidence and Proof at University of Sydney

and Gary Edmond, Professor at University of New South Wales

NSW Attorney General Greg Smith (center) claims that previous laws guaranteeing the right to silence were easily exploited by criminals.

The right to silence when being interviewed or questioned by police would be considered a fundamental legal right by many people.

But it is not a "right" you can exercise in New South Wales any more.

The NSW Parliament has passed criminal justice reforms to "make trials more efficient". However, the changes promise to diminish efficiency and longstanding human rights.

According to the right to silence and the presumption of innocence the defendant need not answer police questions or prove his innocence. The state must prove guilt. The Government claims these rights are being abused, hampering investigation, lengthening trials, and bringing mistaken acquittals.

The first Act introduced by the O'Farrell government requires mandatory disclosure of the defence case. Notice must be given of the nature of the defence, prosecution allegations that the defendant rejects, and prosecution evidence that the defendant objects to.

However, legislation already requires mandatory disclosure of alibi and the mental impairment defence. Courts already possess the power to order more extensive disclosure where necessary.

In 2009 the Trial Efficiency Working Group (TEWG) advised against "blanket application" of disclosure requirements: "[t]he majority of criminal cases are relatively straightforward and the application of full pre-trial processes to all matters would introduce inefficiencies." Following further consideration over Christmas TEWG did not support the government's approach.

Many defendants lack the legal assistance required to properly meet these requirements. (The government has no intention of increasing the legal aid budget.) The court must then decide whether to sanction non-compliance, preventing a defendant from mounting a non-disclosed case or raising an adverse inference.

The second Act is even more problematic. It diminishes the right to silence at the police station. Currently the suspect is cautioned - "You have the right to remain silent. Anything you do say will be taken down and may be used in evidence against you." The reforms discourage silence by creating the risk of an adverse inference. "It may harm your defence if you fail to mention something now which you later

(Sydney Morning Herald)

The government claims the adverse inference is required to break down the "wall of silence". But this is dubious. The reforms apply pressure only to suspects, not witnesses. Anyway, most suspects answer police questions, and those that don't are just as likely to be convicted.

The NSW Act is based upon English legislation of 1994 which made no discernible difference to conviction rates (Home Office, 2000). However, as the NSW Law Reform Commission recognised in 2000, the English approach is subject to "practical and logical objections". Scotland also recently demurred due to the scheme's "labyrinthine complexity".

Contrary to government claims, the adverse inference is not "simple common sense". It raises a host of difficult legal and inferential issues. The inference will only be available if "the defendant failed ... to mention a fact ... [later] relied on in his or her defence".

How does this apply if the defendant provided a brief prepared statement which was later elaborated on at trial? Does the defendant "rely" on a matter that was merely put to a prosecution witness in cross-examination?

Where the defendant does rely on a fact at trial, the inference will only be available if "the defendant could reasonably have been expected' to mention the fact to police. What if the defendant claims he was confused, unwell, under the influence of drugs or drug withdrawal, concerned about revealing guilt for other lesser offences, or protecting the true culprit (from love or fear).

And what if the defendant claims to have remained silent on legal advice?

English judges, in directing juries on these points, have had to develop, according to Professors Roberts and Zuckerman, "easily one of the most lengthy and complicated" directions in the Crown Court Bench Book. The English Court of Appeal notes this has become a "notorious minefield".

(AAP/Dean Lewins)

The difficulties extend to the police station. With so much riding on the police interview, the European Court has held that the inference will be unavailable unless the suspect had legal advice. English police stations have duty solicitors. There is nothing comparable in NSW.

The Government acknowledges that its previously suggested legal helpline is unworkable. Its latest proposal confines the operation of the new laws to cases where the suspect had a lawyer present. The government claims this targets "the higher end of criminal activity". But the restriction may produce some strange consequences. As the Government acknowledges, career criminals may elect not to bring lawyers to the police station to avoid the new provisions. To divide suspects into different classes and encourage this kind of game playing adds to complexity and inequality.

The reforms also put the spotlight on how police conduct interviews. The expectation of defence disclosure brings an expectation of police disclosure. Its absence may provide a reasonable excuse for a suspect's silence - not dignifying an unsubstantiated allegation, or simply not knowing what facts to mention.

Whereas English police provide extensive disclosure, NSW police use disclosure more strategically to extract evidence from the suspect. The new reforms may require significant changes in police practice. These changes may be unwelcome.

The Government's solution is to make the reforms optional. They can be avoided by the police not giving the new special caution. This increase in police discretion provides scope for game playing and discrimination.

Neither of the Government's reforms promise efficiency gains. Both reforms diminish human rights, add to the complexity of criminal justice, and increase the risk of wrongful conviction.