British Parliamentary Report on the Aboriginals in New Holland & Van Diemen's Land 1837

Parliamentary Select Committee on

(British Settlements)

Reprinted, with comments by the

"Aborigines Protection Society."

LONDON

Published for The society by

William Ball, Aldine Chambers, Paternoster Row, And Hatchard & Son,

PICCADILLY 1837.

The Select Committee appointed to consider what Measures ought to be adopted with regard to the NATIVE INHABITANTS of Countries where BRITISH SETTLEMENTS are made, and to the neighbouring Tribes, in order to secure to them the due observance of Justice and the protection of their Rights; to promote the spread of Civilization among them, and to lead them to the peaceful and voluntary recep-tion of the Christian Religion;" and to whom the Report of the Committee of 1836 was referred ; and who were empowered to report their Observations thereupon, together with the MINUTES OF EVIDENCE taken before them, to The House; Have examined the Matters to them referred, and have agreed to the following REPORT:

(This excerpt has been electronically transcribed - check the full report for accuracy)

The inhabitants of New Holland, in their original condition, have been described by travelers as the most degraded of the human race ; but it is to be feared that intercourse with Europeans has cast over their original debasement a yet deeper shade of wretchedness.

These people, unoffending as they were towards us, have, as might have been expected, suffered in an aggravated degree from the planting amongst them of our penal settlements. In the formation of these settlements it does not appear that the territorial rights of the natives were considered, and very little care has since been take; to protect them from the violence or the contamination of the dregs of our countrymen.

The effects have consequently been dreadful beyond example, both in the diminution of their numbers and in their demoralization.

Many deeds of murder and violence have undoubtedly been committed by the stock-keepers (convicts in the employ of farmers in the outskirts of the colony), by the cedar cutters, and by other remote free settlers, and many natives have perished by the various military parties sent against them ; but it is not to violence only that their decrease is ascribed. This is the evidence given by Bishop Broughton.

"They do not so much retire as decay; wherever Europeans meet with them they appear to wear out, and gradually to decay : they diminish in numbers ; they appear actually to vanish from the face of the earth. I am led to apprehend that within a very limited period, a few years," (adds the Bishop), " those who are most in contact with Europeans will be utterly extinct — I will not say exterminated — but they will be extinct." As to their moral condition, the bishop says of the natives around Sydney, "They are in a state which I consider one of extreme degradation and ignorance; they are, in fact, in a situation much inferior to what I supposed them to have been before they had any communication with Europe."

And again, in his charge, "It is an awful, it is even an appalling consideration, that, after an intercourse of nearly half a century with a christian people, these hapless human beings continue to this day in their original benighted and degraded state. I may even proceed farther, so far as to express my fears that our settlement in their country has even deteriorated a condition of existence, than which, before our interference, nothing more miserable could easily be conceived. While, as the contagion of European inter-course has extended itself among them, they gradually lose the better properties of their own character, they appear in exchange to acquire none but the most objectionable and degrading of ours."

The natives about Sydney and Paramatta are represented as in a state of wretchedness still more deplorable than those resident in the interior. "Those in the vicinity of Sydney are so completely changed, they scarcely have the same pursuits now; they go about the streets begging their bread, and begging for clothing and rum. From -the diseases introduced among them, the tribes in immediate connexion with those large towns almost became extinct; not more than two or three remained, when I was last in New South Wales, of tribes which formerly consisted of 200 or 300."

Dr. Lang, the minister of the Scotch church, writes, " From the prevalence of infanticide, from intemperance, and from European diseases, their number is evidently and rapidly diminishing in all the older settlements of the colony, and in the neighbourhood of Sydney especially, they present merely the shadow of what were once numerous tribes." Yet even now "he thinks their number within the limits of the colony of New South Wales cannot be less than 10,000: an indication of what must once have been the population, and what the destruction.

It is only," Dr. Lang observes, " through the influence of Christianity, brought to bear upon the natives by the zealous exertions of devoted missionaries, that the progress of extinction can be checked." The case of these people has not been wholly overlooked at home. In 1825 his Majesty issued instructions to the governor to the effect that they should be protected in the enjoyment of their possessions, preserved from violence and injustice, and that measures should be taken for their conversion to the Christian faith, and their advancement in civilisation.

An allowance has been made to the Church Missionary Society in their behalf, and efforts for their amelioration have been made, and attended with some degree of utility; but much as we rejoice in this act of justice, we still must express our conviction that if we are ever able to make atonement to the remnant of this people, it will require no slight attention, and no ordinary, sacrifices on our part to compensate the evil association which we have inflicted; but even hopelessness of making reparation for what is past would not in any way lessen our obligation to stop, as far as in us lies, the continuance of iniquity. "The evil," said Mr. Coates," resulting from immoral intercourse between the Europeans and the Aborigines, is so enormous that it appears to my mind a moral obligation on the local government to take any practicable measures in order to put an end to it."

In this opinion the Committee entirely concur. A new colony is about to be established in South Australia, and it deserves to be placed upon record, that parliament, as lately as August 1834, passed an act disposing of the lands of this country without once adverting to the native population. With this remarkable exception, we have had satisfaction in observing the preliminary measures for the formation of this settlement, which appears, if we may judge from the Report of the Colonial Commissioners, likely to be undertaken in a better spirit than any such enterprises that have come before our notice.

The commissioners acknowledge that it is "a melancholy fact, which admits of no dispute, and which cannot be too deeply deplored, that the native tribes of Australia have hitherto been exposed to injustice and cruelty in their intercourse with Europeans ;" and they lay down certain regulations to remedy these evils in the proposed settlement.

On the western coast of Australia collisions have not unfrequently taken place between the colonists and the natives, on the subject of which we may adopt the just language of Lord Glenelg : "It is impossible to regard such conflicts without regret and anxiety, when we recollect how fatal, in too many instances, our colonial settlements have proved to the natives of the places where they have been formed; and this too by a series of conflicts, in every one of which it has been asserted, and apparently with justice, that the immediate aggression has not been on our side. The real causes of these hostilities are to be found in a course of petty encroachments and acts of injustice committed by the new settlers, at first submitted to by the natives, and not sufficiently checked in the outset by the leaders of the colonists.

Hence has been generated in the minds of the injured party a deadly spirit of hatred and vengeance, which breaks out at length into deeds of atrocity, which, in their turn, make retaliation a necessary part of self-defence." It is true, that to remain passive under actual outrages, would encourage savages in their perpetration, but we regret that in any instance, punishment, which appears disproportionate, should have been inflicted. We find the natives on the Murray River mentioned as amongst the most troublesome in this quarter ; and in the summer of the year 1834 they murdered a British soldier, having in the course of the previous five years killed three other persons. In the month of October 1834 Sir James Stirling, the governor, proceeded with a party of horse to the Murray River, in search of the tribe in question.

On coming up with them, it appears that the British horse charged this tribe without any parley, and killed fifteen of them, not, as it seems, confining their vengeance to the actual murderers. After the rout, the women who had been taken prisoners were dismissed, having been informed, "that the punishment had been inflicted because of the misconduct of the tribe ; that the white men never forget to punish murder that on this occasion the women and children had been spared; but if any other person should be killed by them, not one would be allowed to remain on this side of the mountains."

However needful it may be to overawe the natives from committing acts of treachery, we cannot understand the principle of such indiscriminate punishment, nor approve of threats extending to the destruction of women and children. " It would also be satisfactory," as Lord Glenelg has observed, " to know that there had been no previous misconduct, or act of harshness or injustice, which had originally provoked the enmity of the natives." We are, however, happy to learn that, in his general policy, Sir James Stirling has pursued conciliatory measures towards the neighbouring tribes, and that measures are in progress for effecting their civilisation.

The natives of Van Diemen's land, first, it appears, provoked by the British colonists, whose early atrocities, and whose robberies of their wives and children, excited a spirit of indiscriminate vengeance, to became so dangerous, though diminished to a very small number, that their remaining in their own country was deemed incompatible with the safety of the settlement.

In their case, it must be remembered, the strongest desire was felt by the government at home, and responded to by the local governor, to protect and conciliate them ; and yet, such was the unfortunate nature of our policy, and the circumstances into which it had brought us, that no better expedient could be devised than the catching and expatriating of the whole of the native population.

There is no doubt that the outrages of the Aborigines were fearful; but while the local "Aborigines Committee," in 1831, who recommended the removal, speak of the "forbearance" exercised both by the government and the greater part of the community, they state that there is the "strongest feeling amongst the settlers that so long as the natives have only land to traverse, so long will life and every thing valuable to them be kept in a state of jeopardy ;" and they intimate their fear that if the measure recommended be not adopted, " the result will be that the whites will individually, or in small bodies, take violent steps against the Aborigines, a proceeding which they cannot contemplate the possibility of without horror ; but which, they do believe, has many supporters in this colony :" they therefore urge the removal under the "persuasion that such a measure alone will have the effect of preventing the calamities which his Majesty's subjects have for so long a period suffered, and of preventing the entire destruction of the Aborigines themselves."'

The governor Colonel Arthur's words on the subject are these: " Undoubtedly the .being reduced to the necessity of driving a simple, but warlike, and, as it now appears, noble-minded race from their native hunting-grounds, is a measure in itself so distressing, that I am willing to make almost any prudent sacrifice that may tend to compensate for the injuries that the government is unwillingly and unavoidably made the instrument of inflicting." 4- The removal accordingly proceeded under the management of Mr. Robinson (which is described by Colonel Arthur as able and humane); and in September 1834 it was so nearly effected, that the governor writes thus: " The whole of the aboriginal inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land (excepting four persons) are now domiciliated, with their own consent, on (excepting s Island." From still later reports it appears that not a single native now remains upon Van Diemen's Land. Thus, nearly, has the event been accomplished which was thus predicted and deprecated by Sir G. Murray:—The great decrease which has of late years taken place in the amount of the aboriginal population, render it not unreasonable to apprehend that the whole race of these people may, at no distant period, become extinct. But with whatever feelings such an event may be looked for-ward to by those of the settlers who have been sufferers by the collisions

*Papers Aboriginal Tribes, p.169. Despatch to Lord Goderich, 6th April, 1833. Papers, 1834.

**Despatch from Lord Gleneig to Governor Sir J. Stirling, 29d July, 1835. Despatch of Sir J. Stirling to Mr. Secretary Stanley, In November, 1834. Report of the Aborigines Committee, Van Diemen's Land, 1830. Part. Papers, No. 259, p. 38. 14 ABORIGINES REPORT.

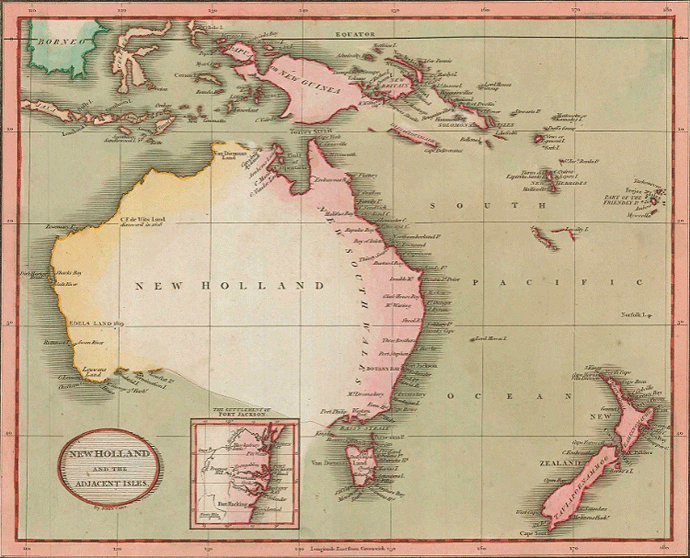

London, 1813. Original colour. 245 x 310mm.

Map shows Australlia not completely charted; the south coast is drawn with a hypothetical line from Lowflat Island to port Philip. With an inset map of 'The Settlement of Port Jackson'

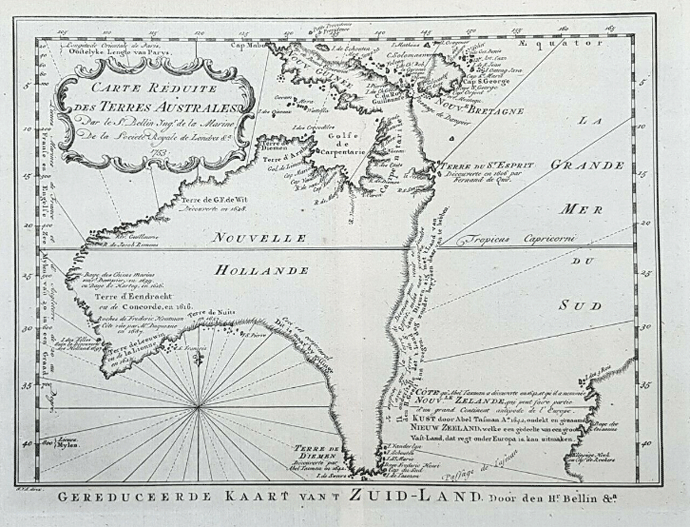

The south coast line of New Holland was in fact known much earlier than the John Cary map was made. Here is a 1753 French Map before Cook navigated the east coast