Every symbolic colonial building in Sydney was placed upon a significant First Nations city site

Sydney's current city is probably the largest urban system ever built from, and upon, an existing city framework and it was built in an unholy silence. So says Sydney based Peter Myers who was an architect on the design team of Jørn Utzon's famous Sydney Opera House at Bennelong Point.

The author claims that Sydney from Port Stephens to Kiama, has always been a relatively low-density urban place, with Port Jackson as its focal point all that the British invaders did was to replace one economic landscape with another, substituting one form of dwelling with another.

From the 'Third City' by Peter Myers, Architecture AU

What if our present historical city was not the first urban structure to occupy the coastal region extending from Port Stephens to Kiama? What would this primordial city reveal, what lessons of history could we learn; just what of this first, pre-invasion Sydney was admitted, and what was denied in the making of our second metropolis?

Well, proving a vast and ancient First Sydney is, like Newton's falling apple, ridiculously easy. I cite Newton because it was the collapse, in 1991, of a section of lime plaster cornice in our circa 1853 Blacket villa, that led me to, maybe, the First Fleet's best-kept secret.

The meaning of the shells

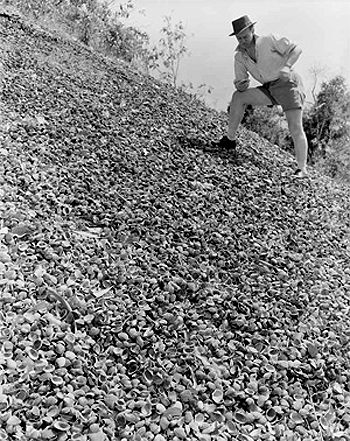

Previously, in 1974, while working in Arnhem Land, I assessed the suitability of a local cement aggregate brick for domestic construction. Unwittingly, the coarse material for this sample had been obtained from a previously undisturbed system of shell middens, some 100 metres wide and extending 20 kilometres along Manakadokajirripa's dunes, east of the Blyth River estuary. I obtained two of these bricks and sent one to Professor Rhys Jones at the Australian National University for analysis. Jones subsequently confirmed that his sample, being made from midden materials up to 7000 years old, was indeed the world's oldest brick containing a machine-pressed 'frog'.

Shell Midden, Weipa Queensland

The mounds are called shell middens and a means of ensuring a sustainable relationship with nature's bounty. Shellfish were an important part of the Aboriginal diet and by discarding the shells on these mounds they kept a visible record of their eating habits.

Meanwhile the plasterers ran a new section of the missing cornice and I, for some reason, kept the original fallen fragment. Then, years later, it hit me: this cornice section contained still unburnt shell fragments! These had to be shell fragments, they could not be partially slaked chips of quarried rock lime, because they had not subsequently hydrated in-situ.

So if Edmund Blacket had specified shell lime for the construction of our house, where did he get it from? The answer is that not only Blacket, but every builder in old Sydney town, obtained building lime from the region's approximately 200 shell lime kilns. So we, or rather our predecessors, burnt the shell monuments of the prehistoric or First City, in order to construct the present historic or Second City.

So much for Terra Nullius. The First Fleet shipped no building lime; it was assumed that limestone deposits would be quickly found and that, in the interim, buildings could be constructed from the dense coastal forests noted by Cook. But the British did not anticipate white ants, so their hurriedly constructed timber buildings just as hurriedly collapsed and, bereft of building lime, the first attempts at brick and masonry construction could not withstand even a summer shower. Phillip, by all accounts an enlightened Governor, was now forced to exploit the fabulous shell monuments lining the inlets and estuaries of Port Jackson, Botany Bay and beyond.

I use the term 'shell monuments' deliberately; to describe them as 'kitchen middens' or 'discarded refuse' 1 is a limited vision of their true intent. There are recorded sightings of shell monuments 12 metres high along the water's edge (perhaps significantly, that is equivalent to the height of the southern podium of Jørn Utzon's Sydney Opera House). Can you imagine how many thousands of years of gathering and accumulation went into their making? So Phillip, whatever may have been his aesthetic, was forced to destroy the urban framework of a by-now tragically depleted Aboriginal population.

It was really an impasse of refinement, where neither the citizens of the First City, nor the British insurgents could conceive of the other's sensibilities. This fearful dilemma is most poignantly, if unintentionally, portrayed in the title vignette to Hunter's journal.

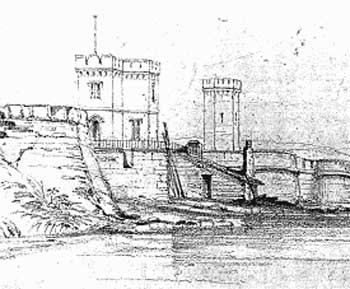

Lime kiln, Cooks River Dam c1870s

(Mitchell Library)

I think that Sydney's ancient locals just couldn't take another minute of it! After all, the British were burning not only their past, as represented by their shell monuments, but also were - for their most significant buildings, such as Fort Macquarie - consuming the live shell beds, because these were known to make the strongest possible lime mortar. So, now deprived of their past and their future shellfish resources, the First City's Aboriginal communities found themselves without a present. Indeed, it is prescient that the first and largest shell lime kiln was on the eastern shore of Bennelong Point: not so much Phillip's Arcadian Farm Cove as remnants of the First City's shellfish Farm Cove! If only La Perouse had prevailed; if only because the French had a long tradition of architectural treatises, going right back to Philibert de L'Orme (1500-1570), wherein the technology and merit of pisé construction are described.

Only several years after 1788, the immortal François Cointeraux's first earth building pamphlets were published. Although gatherings of Cointeraux's pamphlets are known to have been in America before 1800, we must also acknowledge Georgian Britain's grinding francophobia, which alone guaranteed that this amazing and rational technology would never sully their new colony at Port Jackson. But to return to our place, the entire house is sandstock brickwork laid up in shell lime mortar. I had no trouble in finding bricks with intact mortar beds containing whole cockle shells. The argument (first put by Phillip2) that the so-called 'original' population was small - around 1500 between Botany and Broken Bays - only confirms the antiquity of the first Sydney, because there is no way that this much lime could have been extracted between 1788 and 1888 from less than one million cubic metres of shells, dead or alive.

Second Sydney

Parramatta Road as a 'made road' was officially opened by the invaders in 1811, considered one of Sydney's oldest roads and Australia's first highway between two cities. However it was a First Nations 'walking track' before that and many other roadways in Sydney used tracks that were part of the 'First City'.

Thus the construction of the second, historic Sydney was really a 'reworking' of the city fabric that Phillip discovered in 1788. Brick clays were discovered by clearing away managed forest cover, while quarried sandstone caves and outcrops would have been adorned with rock engravings at least equal to the fabulous surviving examples recorded by W.D. Campbell a century later3 . The beginnings of any colonial enterprise are proverbially insensitive to local cultures, so why should we be surprised that Phillip ignored, or chose to ignore, the very definite indications of an existing urban structure?

The fact that any substantial colonial pastoral holding had its homestead sited exactly on top of a former Aboriginal campsite should be proof enough that the same siting rules applied to historic Sydney. Thus, Bennelong Point was a most important Aboriginal site, upon which a number of very large shell monuments once stood, and which we can also be sure was overlooked by an exquisite range of rock engravings, just precisely where Edward Blore's Government House was subsequently located.4

The same applies for all the significant buildings and places of historic Sydney. Do we seriously believe that we 'discovered' the rock swimming pools along Sydney's beaches, or that the few remaining sandstone ledges along Woolloomoolloo Bay have only recently been frequented by local Aboriginal families, reminiscing as they scan the water surface for rushing small fry? Every important colonial building was placed upon a significant First City site, and that goes for both Sydney University and Gladesville Asylum, for example: if you consider their sightlines, and then look at the map in Campbell, it is obvious that these sites have been occupied since remote antiquity.

The author claims that Sydney from Port Stephens to Kiama, has always been a relatively low-density urban place, with Port Jackson as its focal point all that the British invaders did was to replace one economic landscape with another, substituting one form of dwelling with another.

The vast suburban grids of the Second City also continue traditions of the First. The benign environmental conditions that favoured a decentralised urbanism for the First City also easily accommodated the English colonists. An effortless outward expansion of the Second City was thus foreshadowed, with surveyors carefully dividing Port Jackson's hinterlands into regular quarter-acre subdivisions. The subsequent housing stock is, even today, endearingly temporary, while the contained landscape is appropriately massive - just like it was in the ancient past.

Sydney's Second City is probably the largest urban system ever built from, and upon, an existing fabric. Certainly no historical city in the Americas is so directly constructed from the urban structure of a preceding civilisation, nor made with a more culpable silence. Our region, from Port Stephens to Kiama, has always been a relatively low-density conurbation, with Port Jackson as its locus: all we actually did was to replace one economic landscape with another, substituting one form of dispersed, temporary dwelling with another.

Certainly, the introduction of, for example, corrugated iron sheeting, by Henry Parkes in 1847, greatly aided the colonists in their adaptive settlements. However, I now believe that these frontier materials are important only insofar as they emulate those technologies, such as bark sheeting, that were then used by the Aboriginal communities to make their temporary, moveable shelters. Similarly, the Garden City movement is often cited as the catalyst of Australian suburbia, yet it is worth considering, via Norman Tindale's magnificent overprinted maps,5 just how diligently we have supplanted Aboriginal Australia's language densities with our own dispersed populations.

Sydney based Architect Peter Myers was on the design team of Jørn Utzon's Sydney Opera House at Bennelong Point. He also lectured at Sydney University - Our story covers Sydney's 'First City' and 'Second City' only, You can read Peter Myers article that includes an outline of his 'Third City' concept here.

From Paul Keating's speech for the Bankstown City Silver Jubilee on 27th May 2005 "An architect friend of mine, Peter Myers said the 'First City' was the place lived in and frequented by Aboriginal people, distinguished by shell-midden mounds of the scale and of the kind which existed at Bennelong Point. In Myers' concept, the 'Second City' is the one we created between European settlement and now. Victorian, Edwardian, modern, postmodern."

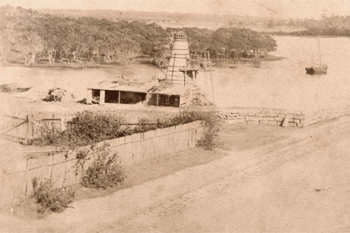

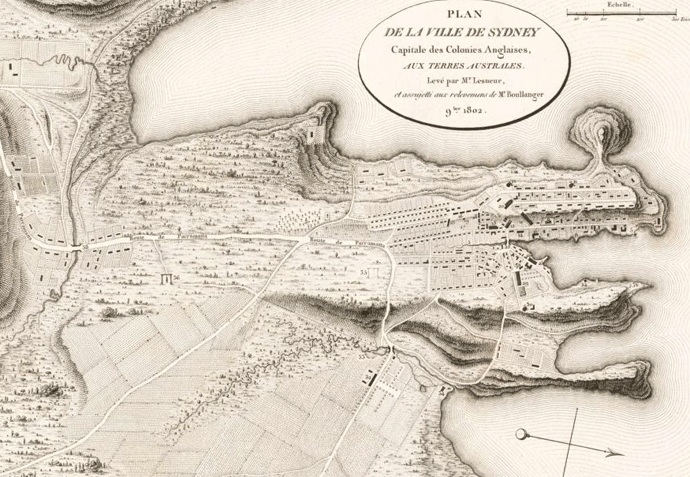

Click Image to enlarge/expand

(National Library of Australia)

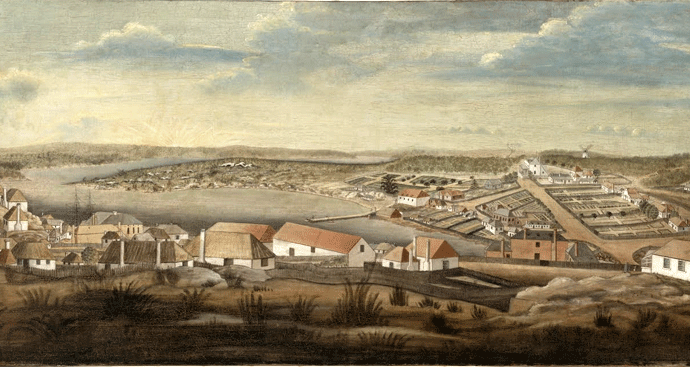

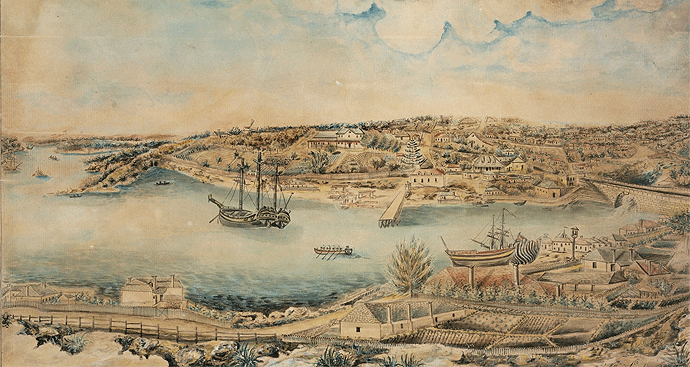

Sydney by George William Evans 'circa 1803'. In this case the wooden bridge can be seen, suggested it was rendered in the first half of 1803 (or earlier)

2. Mackaness, George, 1937. Admiral Arthur Phillip, p. 140.

3. Campbell, W.D, 1899. Aboriginal Carvings of Port Jackson and Botany Bay.

4. The sandstone outcrop where Blore's Government House now stands can be seen in the oil painting catalogue No. 9, Sydney: Capital New South Wales, circa 1800, artist unknown, in the Picture Gallery at the State Library of NSW.

5. To accompany his 1974 book, Aboriginal Tribes of Australia, Professor Norman Tindale overprinted Tribal Boundaries in Aboriginal Australia onto the standard four-sheet map of the continent then produced by the Department of National Development in Canberra.