You are here

Search by issue

Media Releases & News

- SU Media Releases

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2022

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- General Statements

- Sovereign Treaties: International Law

- Walkout Statement from Sacred Fire

- Proclamation (with video Readings)

- UDI's Explained

- What is 'Decolonisation'?

- Uluru Statement from the heart

- Sovereign Manifesto of Demands

- NO CONSENT to Recognition

- Submission on ILUA Amendment

- Uluru Statement video testimonials

- Uluru Statement grassroots videos

- Complexity of Treaty and Treaties

- Understanding Treaty & Treaties

- Official SU Meetings

Sovereign Union Menu

- Self Governance

- International

- Treaty - Treaties

- Sovereignty

- General Principles of Sovereignty

- First Nations sovereignty defined

- The Sovereignty Debate

- Sovereignty into Governance

- Reform: Practicing sovereignty

- Sovereignty after Mabo

- What about Sovereignty?

- Current sovereignty debate

- Sovereignty protest Qld

- Research papers & Theses

- Sovereignty never ceded -thesis

- SA sovereignty challenged

- Rosalie Kunoth-Monks leads the way

- Pacific Islanders Act 1875

- Asserting Aboriginal Sovereignty

- Aboriginal rights then & now

- Michael Kirby Oration

- Academic Paper : Songlines

- John Howard recognised sovereignty

- Queen Victoria: Crown owns nothing, Aborigines sovereign

- Rejecting 'recognition'

- Yingiya Mark Guyula Speach

- New Way Summits

- Decolonise

- August

- Australia: UN Questionnaire

- July

- Law against Genocide Bill

- Rally: 'Let us go Home'

- Ray Jackson: 30 years of light

Special Features

- History

- During Invasion

- Invasion

- 1788-2014 Invasion to Resistance

- 'The condition of the natives' 1905

- Mapping QLD massacres

- Cooks Instructions & Diary

- Whites & Blacks during the colonisation in the late 19th Century

- Australia's history of slavery

- Dad 'n Dave - The Qld killing fields

- Treatment of Aboriginal Prisoners

- 'Conspiracy of silence' blood baths

- British Parliament Report 1837

- Culture

- Horrors of North West WA

- Ignorance & Racism

- Invasion

- Post Invasion

- Stolen Remains and Collections

- Culture

- Kitty Wallaby: Dreamtime & colanisation

- Improve heritage management

- Unlock secrets of rock art

- Kurlpurlunu found in Central Australia

- Forgotten' Woolwonga tribe for 130 years

- First Nations rock art is at risk

- Language diversity threatened, study

- Languages Treasure trove

- Pressure to lose values and culture

- Languages reveal scientific clues

- Ignorance & Racism

- Father of the Stolen Generation

- Aboriginal counting myth won't go away

- Pleading letters to 'Protector'

- 1926 plan for an Aboriginal state

- First prisoner abuse inquiry 1905

- Legalised slavery: hidden reality

- The second dispossession

- Rottnest Island internment camp

- Meston's 'Wild Australia' Show 1892-1893

- Stolen Wandjina: Cultural Appropriation

- Whitefellas destroyed our bible

- Fraser Island Death Camp

- Intervention to kill self-determination

- Ongoing Warfare

- Pre Invasion

- Culture

- Genesis

- Out of Australia - Not Africa

- confirmation of genetic antiquity

- WA's Mid West History 30K

- 'Australian' peoples were first Americans

- How First Nations saw the Stars

- Ice Age struck First Nations people hard

- Kimberley paintings could be oldest

- Misunderstand First Nations science

- Sea-Level recorded

- James Cook's Secret Instructions - 30 June 1768

- Trading & Hospitality

- Landcare, Science, Agriculture

- Captain Cook

- During Invasion

- The Frontier Wars

- Memorial Marches

- The Frontier Wars

- Anzac Gathering 2012

- Aboriginal servicemen honoured

- 1905 Report WA's North

- Anzac Day Videos

- Battle for FF memorial

- From invasion to resistance

- Frontier Wars Remembered 2016

- Image Galleries

- Invasion & Sovereignty

- Invasion Day Callout for 26 January

- Memorial ignores frontier war

- The Freedom Fighters

- Truth about the Gulf country

- Conflicts/Massacres

- Massacres & Trophies

- Mixed Media

- Canberra 2016

- Closing the Homelands

- Homelands explained

- Central Articles

- Closing Homelands for mining

- Vital for ecosystems

- Terra nullius never went away

- Barnett's plan to axe homelands for years

- Fed Gov't $100 million deal with states

- Mining: $10,000 job sweeteners

- Abbott rejects international law

- Barnett's War on Health

- Anatomy of Racism in 2015

- Food supply autonomy needed

- Freedom Summit: WFD Media Release

- Funding: Confusing-fractured-racist

- It's OK to discriminate

- The demise of Coonana community

- Sovereign Union Articles

- Reports by State & Territory

- Video - Images - Audio

- Rallies

- Media Reports

- Homeland Closures

- 'Recognition' Constitution

- Nuclear Waste Dumps

Key Topics & Issues

- NT Detention Hearings

- NT Intervention

- Sovereign Embassies

- All Embassies - Map

- Embassies

- Canberra Tent Embassy

- Perth Sovereign Embassies

- Portland Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Embassy - Home

- What is Brisbane Embassy?

- 2013 content

- 2012 content

- New Stolen Generation rally

- Police arrest sovereigns

- Politically motivated eviction

- Brisbane - Eviction notice

- Brisbane Embassy meets CMC

- Brisbane conference 2012

- Charges dropped but ...

- Council meets Elders

- Embassy arrestees protest

- Embassy midnight raid

- Embassy to be shut down

- Fire destroys Embassy

- Musgrave heritage listing

- Sovereigns charges dropped

- Moree Sovereign Embassy

- Broome Tent Embassty

- Woomera Sovereign Embassy

- Airds Sovereign Embassy

- Gugada Sovereign Embassy

- Tent Embassy in Airds, Campbelltown

- Call for Embassy tolerance

- Embassy Articles & Media

- Land, Sea & Water

- Northern Murray Darling Basin

- Water Treaty Talks: Murray-Darling Basin Nations

- Mining Country

- Adnyamathanha people of the rocks

- Ancient approach to global emissions

- Danger: Developing the North

- First Nations Land Management

- Historical sites in NSW

- Clark and Mansell: trading beef

- David Suzuki: Aboriginals best bet

- Dingoes may save wildlife

- Fires support mammals - research

- First Nations had villages and farmed

- Homelands vital for fragile ecosystems

- Hunter gatherers Myth - Bruce Pascoe

- Kangaroos win after hunt with fire

- Race to protect ancient rock art

- Kakadu Park 40th Anniversary

- Land rights and the government

- Native 'wild' rice in Australia

- Native Title amendments slammed

- Ngoongar Grower group using Native Youlks

- WA Aboriginal Heritage Act overview

- Sovereign Neighbours

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- December

- October 2013

- September 2013

- Emergency Protest of Illegal Deportation

- FF activists a test for Abbott government

- West Papuans Deported to Port Moresby

- Six West Papuan's flee after ceremony

- Freedom Flotilla claims success

- Sacred water and fire celebrated

- Ceremony completed in secret

- Military buildup in destination port

- Men released: Treason charges pending

- Julie Bishop incites military action

- Threats to turn back boat

- Four arrested at FF Welcoming

- Time for human rights in Papua

- August 2013

- Media Files

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- Atooi Unification Ceremony

- Atooi now has jurisdiction

- Australia & Fiji union

- Canada Day: Time of Mourning

- Canada First Nations alliance

- Canada: Commercial fishing rights

- India: Ruling against mining co

- Indigenous rights struggle

- North American Indians seek Sovereignty

- Statue honors US freedom fighters

- The Creation of one world gov't

- Vanuatu: Pacific custom land tenure

- Arizona tribal law system

- Canada: Tsilhqot'in peoples win ruling

- Embassy meets Indonesians

- Grandmothers: worst ever stealing

- Ibans acquired native customary rights

- Maori did not cede sovereignty

- UN: Canadian Aboriginals in crisis

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- The Invasion

- A day of sadness

- Health and Social Issues

- Suicides & Depression

- Suicides just happened?

- Nothing will be done about the suicides

- First Nations suicide rates

- Gov't not listening - People die

- 77 suicides in SA alone

- 996 deaths by suicide

- Hundreds will suicide if we wait

- Suicides: 'A humanitarian crisis'

- Suicide is humanitarian crisis

- Suicide epidemic worldwide

- Noongar x3 suicide rate

- Falsely arrested & drugged

- Cashless Welfare Card

- Family breakdowns causing repeats

- General Health Issues

- Government Policies

- Youth suicide at crisis point

- Negatively framing policies

- A little boy who hid under the bed

- Defend and Extend Medicare

- Call for help results in children stolen?

- Doctors in communities in WA reduced

- Children and human rights

- Our children more likely to be removed

- Justice? wake up WA

- Need for Bilingual schools

- Racism Effects

- Rosie Fulton

- Work-for-the-Dole Unhealthy

- Youth lost in prisons: Amnesty

- Suicides & Depression

- Gross Abuse

- Genocide and apartheid

- National

- States & Territories

- Suicides

- Imprisonment & Deaths

- International Critisism

- Genocide

- More Gov't Abuses

- Mining and Destruction

- Racism

- Racism Game in Australia

- 27% say it's OK to be racist

- Abbott backs out of Racism changed

- Genocide by Apartheid Australia

- How Bolt should be punished

- Racial discrimination in Australia

- Racism Media

- Racism driver for ill health

- Racism is a health issue

- Racism worse than Sth Africa

- Reform: Just Ask Black Australia

- Unpacking White Privilege

- Welcome to Dja Dja Wurrung Country

- White Australian National Anthem

- Solidarity

Media & Resources

Activism and Politics

- Activism

- Homelands

- For the record: Sovereignty Never Ceded

- Freedom Fighters memorial call

- Anthony Fernando 1864–1949

- Fernando's Ghost - Transcript

- Historic Videos and Images

- Australia’s dirty secret

- Deebing Creek development

- Pilbara pastoral strike

- Pro-Black Isn't Anti-White

- Truth Telling Uluru Statement

- UN slams anti-protest laws

- Whitlam: Legacy of Wave Hill

- Winyirin Bin Bin, Pilbara Strike

- Politics

'I was stolen from my mother when I was two years old'

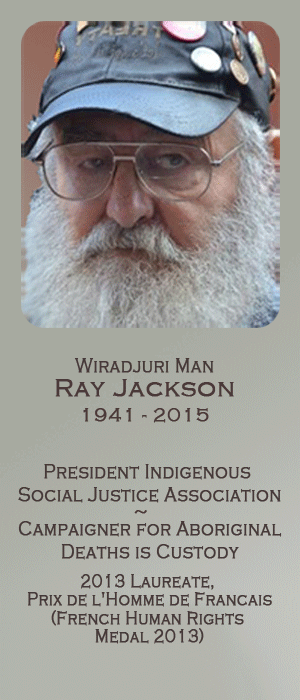

The late Ray Jackson

By Ray Jackson, 3 August 2014

It was 1943, I was two years old and my mother - an Aborigine - was married to a white Australian when he went and gave his life for our country.

All I know is that my father was a soldier and he went up to Papua New Guinea. He was killed on the Kokoda Track and instead of giving his wife a war widow's pension, the bloody government came and took his children away. Because of my mother's Aboriginality.

There were four children at that point in time and I was the third. I think there were two boys and two girls. We were split up, the four of us, we were split.

My name was then changed to fit the adopted family.

I went into, I believe, a Catholic home, where I lived for a year. Then I was given out to another white family and went from there.

When I went to primary school in 1946, after the war and when the migrants started to come out, for a few years I copped sh*t. I was different, I wasn't white but I wasn't black either. So what the hell was I?

Maybe that's when the walls went up, surrounding myself in all this crap.

When I found out about the sob side of my birth, I was in my mid-30s, married with four children.

In my mid-teens, I found out that I was adopted; my cousin and I were having a fight and he made a statement, something along the lines, "you're not even a member of this family", so I asked my [adoptive] mum and she denied it at that time.

I had the opportunity to make a decision as to what I was going to do. Was I going to proceed to find the family? For personal reasons, I decided I had my own family.

I didn't bother.

Maybe that was wrong, maybe I should have done something, but I didn't.

I struggled with this for many years. My mother was of that era where she was frightened to go into the Aboriginal side of my birth.

Getting information from her was like dragging teeth out of a chook, she didn't want to talk about it. I must admit I had the sh*ts with her for doing that. I don't know whether that's right or wrong, I'm 73 now and that's a long time ago. I've had to live with that knowledge for 40 years.

I'd never tried to hide my Aboriginality, but I never came out of the cultural closet, so to speak.

That didn't happen until 1991.

Because of the lack of records, my major stumbling block is not knowing my family name. I still don't know. I haven't tried to locate my brothers or sisters, I don't think they've tried to locate me. My siblings are out there somewhere. Where though, I don't know.

The number of children being taken these days is horrendous. I've read about this. I've seen it. I've tried to help families who've had their children taken, but you're fighting a behemoth.

To take the coppers on is bad enough, but to try and take on a government and its policies, no one out there will listen to you.

I have the greatest admiration for the grandmothers from Gunnedah, who kicked this all off.

I've met some of these grandmothers, I've been to their homes. They are not unfit people. They are not living in some drunk and drug-addicted slovenly hell hole.

And yet the government says these people are not suitable.

Yes we do have drunks, yes we do have druggies, some of them are mothers even, but in the wider family, not all of them are drunk or drug-affected.

When you walk into an Aboriginal house, the first thing you see is a wall covered with photos. Photos of family of those who have gone, those have just come and those who are in between and growing.

Walk into the kitchen, the fridge is covered with children's drawings. That is a normal home. That is pride in your family and children, and that is not being recognised.

These people need assistance, they need help; they don't need their children taken from them.

Ray Jackson, President of the Indigenous Social Justice Association.