Canada: Ditching the Papal Bull(shit) and sovereignty

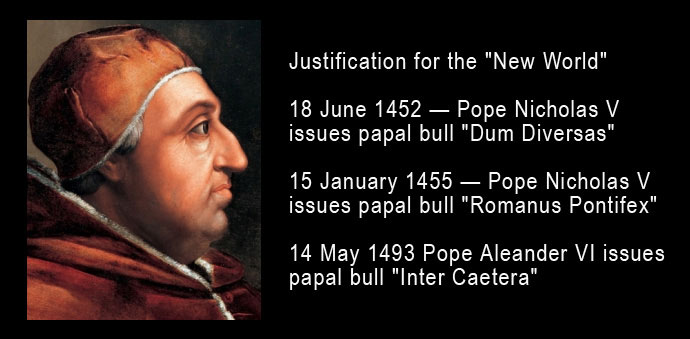

These three edicts served as the foundation and justification for the Doctrine of Discovery and set in place a catastrophic chain of events for First Nations Peoples.

Senwung Lu, OKT Law

On May 1, 2016, First nations people from Canada organised a Long March to Rome and met with Pope Francis and requested him to rescind the Papal “Bulls of Discovery”.

Canadian Perspective

So what exactly do these Papal Bulls, both of which are over 500 years old, have to do with Indigenous rights in Canada today?

Enlarge image

Long March to Rome - 2016

Enlarge image

The Papal Bulls of Discovery are an important piece of a larger idea in international law, called the Discovery Doctrine, which holds that when European nations “discovered” non-European lands, they gained special rights over that land, such as sovereignty and title, regardless of what other peoples live on that land.

As applied to Canada, a good place to start in exploring these issues might be the 1990 Supreme Court of Canada decision of R v Sparrow. This was the first time the highest court in the Canadian legal system had a chance to deal directly with s.35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, which for the first time explicitly enshrined the protection of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Constitution of Canada.

In Sparrow, the Supreme Court of Canada had a generational chance to lay out an understanding of the place of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Canadian constitution in a way that took a clean break from Canada’s colonial past. But instead the Court began by saying:

“It is worth recalling that while British policy towards the native population was based on respect for their right to occupy their traditional lands, […] there was from the outset never any doubt that sovereignty and legislative power, and indeed the underlying title, to such lands vested in the Crown.” (Sparrow, p 1103)

From this position, it was not a far leap for the Court to later say in the Van der Peet case that the law must help “the reconciliation of the pre-existence of [A]boriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.” But as the Court also said in Van der Peet, it is the existence of the Aboriginal societies, and their rights that need proving in the courts; the sovereignty of the Crown is just taken as a given.

In practical terms, there are two sets of implications that flow from this position. First, unless an Indigenous community proves to a court’s satisfaction that it has exclusive occupation or control of a territory, the default understanding of the Canadian legal system is that that territory is Crown land, even if Crown officials and settlers have never set foot on that land. Second, even if an Indigenous community can prove that they have an Aboriginal right, Aboriginal title, or a Treaty right, that right is always potentially subject to infringement by the Crown.

What connects all of these positions is that the default owner of land, and the default holder of legal jurisdiction in Canada, remains the Crown. When Indigenous communities have Aboriginal rights under Canadian law, those rights are understood to modify the default sovereignty and title of the Crown, but the Crown retains the jurisdiction to infringe those rights, at least to the extent that they can get a court to agree that the infringement is justified.

So how did Canadian law get to the idea that Crown sovereignty is presumed to exist, but the Indigenous presence must be proven? It will be helpful to go back to the Sparrow case, where the SCC said that “there was from the outset never any doubt that sovereignty and legislative power, and indeed the underlying title, to such lands vested in the Crown.” One of the most remarkable things about this reasoning from the Canadian Court is that it cited as authority for this proposition the 1823 decision of the US Supreme Court, Johnson v M’Intosh.

Johnson v M’Intosh was a contest between two settlers, both of whom argued that they had good title to a piece of land in Indiana. Johnson could trace his title to a settler who bought land from the Piankeshaw Nation in 1775. M’Intosh, on the other hand, traced his title to a land purchase from the Piankeshaw Nation by the United States government of the same land, but the purchase took place in 1805. The conventional common law understanding would have been that Johnson should win against M’Intosh, because the Piankeshaw Nation, already having been sold the land once in 1775, had nothing left to sell to the Untied States in 1805.

However, the US Supreme Court decided in favour of M’Intosh. Why? Because of what the Court called the Discovery Doctrine: the idea that “discovery” of a non-European land by representatives of a European monarch gave that monarch an exclusive right to buy lands from the Indigenous peoples of the area. And since the US government was the successor to the British Monarch who “discovered” this area, only the US government had the right to buy lands from the Piankeshaw Nation. Therefore, M’Intosh won.

Tellingly, the US Court said this about the Discovery Doctrine:

“In the establishment of these relations, the rights of the original inhabitants were in no instance entirely disregarded, but were necessarily to a considerable extent impaired. They were admitted to be the rightful occupants of the soil, with a legal as well as just claim to retain possession of it, and to use it according to their own discretion; but their rights to complete sovereignty as independent nations were necessarily diminished, and their power to dispose of the soil at their own will to whomsoever they pleased was denied by the original fundamental principle that discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it.” (underlining added)

The US Supreme Court, though, did not see itself as coming up with this Discovery Doctrine by itself. Instead, it said that “The history of America from its discovery to the present day proves, we think, the universal recognition” of the Discovery Doctrine.

And of course, by “universal recognition”, the Court meant recognition by Europeans and their settlers. The Discovery Doctrine was a recognized principle of international law, which of course arose out of the relationships between European countries. And two of the most important sources of this principle of international law were the Papal Bulls of Romanus Pontifex (1455) and Inter Caetera (1493).

These Bulls purported to give Spanish and Portuguese monarchs the right to lands and jurisdictions over any lands that they discovered, based on the idea that the spread of Christianity to non-European peoples gave them the right to do so. Rather than rejecting this principle, other European monarchs, such as the French and British monarchs, simply sought to modify the rule so that they could also gain lands and jurisdiction by discovery as well. For example, King Francis I of France convinced Pope Clement VII to interpret Inter Caetera to apply only to lands that had been “discovered” by the time that it was issued in 1493, so that France could legitimately claim discovery and jurisdiction over Canada, which Jacques Cartier “discovered” in 1534.

As can be seen from the above discussion, so much of international and Canadian law is so enmeshed with the Discovery Doctrine that a repudiation of these Bulls by Pope Francis will probably not, in and of itself, immediately change how the Doctrine is being applied on the ground. However, just as the Pope showed leadership at the dawn of European colonization in legitimating imperialism, he has a chance now to show leadership in repudiating that legacy.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has issued some Calls to Action that are highly relevant to this issue. Call #48, for example, calls upon the churches of Canada to adopt and comply with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. UNDRIP establishes, among other things, a right of Indigenous peoples to their lands and a right not to have their lands taken from them without their free, prior, and informed consent (Arts. 10, 26, 32). Indigenous peoples also have a right to self-government (Arts. 4, 5, 18, 19, 20, 23, 33). The vision of legally legitimated European imperialism articulated in Romanus Pontifex and Inter Caetera are not at all consistent with UNDRIP, and Pope Francis has an opportunity to update the stance of the Church in repudiating those Bulls.

But the opportunity of moving past European imperialism does not belong exclusively to the Pope. TRC Call to Action #45, for example, explicitly calls on the Government of Canada, on behalf of all Canadians, to repudiate the Discovery Doctrine and implement UNDRIP.

Canadians have elected a new federal government who promised to implement all of the TRC Calls to Action. Settler Canadians now have an opportunity to reset their relationship with Indigenous Canadians on a different footing. Under the paradigm of European imperialism, there may indeed have been “universal recognition” that “discovery” and the planting of flags could indeed give a foreign king title to Indigenous lands, and jurisdiction over Indigenous peoples. Indeed, that is how the Canadian state has been built. But there are alternatives, such as seeing the treaty relationship as a basis for shared sovereignty. Settler Canadians have a chance to recast their legal and political institutions, in a way that sees Indigenous Canadians as neighbours, rather than subjugated peoples. And surely no one wants a neighbour who thinks he can take over your front yard just by sticking a flag on it.