Fighting for justice when your skin's black

Expand

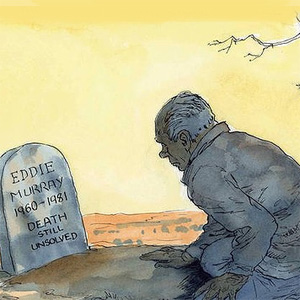

Illustration: John Spooner

John Pilger The Age October 4, 2012

Arthur Murray was an Australian hero who spent his life pursuing the truth of his son's death in custody. But does anyone know his name?

Arthur Murray died the other day (2012). I turned to Google Australia for tributes, and there was a 1991 obituary of an American ballroom instructor of the same name.

There was nothing in the Australian media. The Australian newspaper published a large, rictal image of its proprietor, Rupert Murdoch, handing out awards to his employees. Arthur would have understood the silence.

I first met Arthur a generation ago and knew he was the best kind of trouble. He objected to the cruelty and hypocrisy of white society in a country where his people had lived longer than human beings had lived anywhere.

In 1969, he and Leila brought their family to the town of Wee Waa in New South Wales and camped beside the Namoi River.

Arthur worked in the cotton fields for $1.12 an hour. Only "itinerant blackfellas" were recruited for such a pittance; only whites had unions in the land of the "fair go".

Working conditions were primitive and dangerous. "The crop-sprayers used to fly so low," he told me. "We had to lie face down in the mud or our heads would've been chopped off. The insecticide was dumped on us, and for days we'd be coughing and chucking it up."

Arthur and the cotton-chippers made history. They went on strike, and more than 500 of them marched through Wee Waa.

The Wee Waa Echo called them "radicals and professional troublemakers", adding "it is not fanciful to see the Aboriginal problem as the powder keg for Communist aggression in Australia".

Abused as "boongs" and "niggers", the Murrays' riverside camp was attacked and the workers' tents smashed or burnt down.

Although food was collected for the strikers, hunger united their families. Leila would wake before sunrise to light a wood fire that cooked the little food they had and to heat a 44-gallon drum, cut in half lengthways, and filled with water that the children brought in buckets from the river for their morning bath. With her ancient flat iron she pressed their clothes, so that they went to school "spotless", as she would say.

"Who in the town supported you?" I asked Arthur. He thought for a while. "There was a chemist," he said, "who was kind to Aboriginal people. Mostly we were on our own." Soon after the cotton workers won an hourly rate of $1.45, Arthur was arrested for trespassing in the grounds of the RSL Club.

His defence shocked the town; it was land rights. All of Australia was Aboriginal land, he said.

On June 12, 1981, Arthur and Leila's son, Eddie, aged 21, was drinking with some friends in a park in Wee Waa. He was a star footballer, optimistic of touring New Zealand with the Redfern All Blacks rugby league team. At 1.45pm he was picked up by the police for nothing but drunkenness. Within an hour he was dead in a cell, with a blanket tied round his neck.

At the inquest, the coroner described police evidence as "highly suspicious" and records were found to have been falsified. Eddie, he said, had died "by his own hand or by the hand of a person or persons unknown". It was a craven finding familiar to Aboriginal Australians.

Everyone knew Eddie had too much to live for.

Arthur and Leila set out on an extraordinary journey for justice for their son and their people.

They endured the ignorance and indifference of white society and its multi-layered political and judicial bureaucracies. They won a royal commission, only to see the royal commissioner, a judge, suddenly appointed to a top government administrative job in the critical final stages of the hearing.

They eventually won the right to exhume Eddie's body, and suffered terribly in the process, in order to prove the true cause of death, and they proved it; his sternum had been crushed by a blow while he was alive. And they reaffirmed how common their story was. "They're killing Aboriginal people … just killing us," Leila told me. Today, Aborigines are incarcerated at five times the rate of blacks in apartheid South Africa, and their death and suffering in custody is widespread.

In 2000, then NSW police minister Paul Whelan met Arthur and Leila in his office in Sydney and ordered a special investigation.

He promised them this "would not be the end of the road". There was no serious inquiry and the minister retired to his stud farm. He has returned none of my calls.

Leila could not read, yet this remarkable woman memorised almost every document and judgment. She died in 2004, broken-hearted. Incredibly, Arthur reached the age of 70 when many Aboriginal men are dead much earlier.

In a typical case this year, CCTV footage in Alice Springs police station showed a policewoman cleaning blood off the floor while a stricken Aboriginal man was left to die.

Australia, said Prime Minister Julia Gillard on September 26, deserves a seat at the top table of the United Nations because it "embraces the high ideals" of the UN. No country since apartheid South Africa has been more condemned by the UN for its racism than Australia.

When I last saw Arthur, we walked down to the Namoi riverbank and he told me how the police in Wee Waa were still frightened to go into the cell where Eddie had died and had pleaded with him to "smoke out" Eddie's spirit. "No bloody way!" Arthur told them. Peace to all their spirits; justice to all their people.

John Pilger is an award-winning journalist, author and documentary maker.

We have copped a lot of ignorant abuse in the past, but it makes you wonder when a former state coroner openly attacks Aboriginal families who have been through hell.

Arthur Murray