Carved trees of First Nations Peoples from Western New South Wales

Gamilaroi and Wiradjuri women should note that traditional cultural laws prohibit women to view the images of grave sites that are pictured on this page.

Slideshow converted to an 8 page file pdf

Trees taken from Collymongle station in 1949

Courtesy the H. Balfour collection, South Australian Museum (ref. no. AA 17/1/7)

13 January 2015

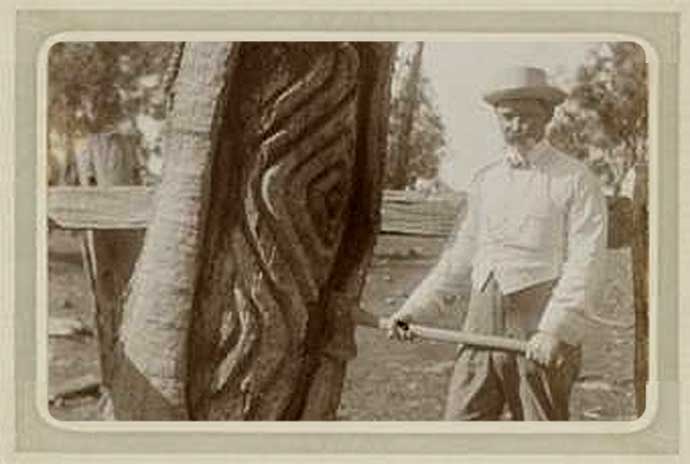

A carved tree photographed near Dubbo, NSW

(Photograph by Henry King)

Click thumbnails to expand and enlarge

Click thumbnails to expand and enlarge

For thousands of years Aboriginal groups in central NSW marked important ceremonial sites by carving beautiful, ornate designs on the trunks of trees. The carvings, comprising symbolic motifs, intricate swirls, circles and zigzags, were intended to be long-lasting but, instead, only a handful of the trees on which they were carved are still alive today.

In the early 1900s several amateur anthropologists, including Clifton Cappie Towle, showed an interest in indigenous culture, documenting and photographing rock art, ceremonial sites, and examples of tree carvings. Thanks to their photographs, which are currently on display at the State Library of NSW, the art form can be glimpsed by the public.

Exhibition curator Ronald Briggs says the practice of carving trees was abandoned more than 100 years ago, which makes it difficult to understand the original meanings behind the designs.

"I think of them as a warning to people walking by that this is a special area, a warning to you that the site is spiritually significant," he says. "They're really quite powerful."

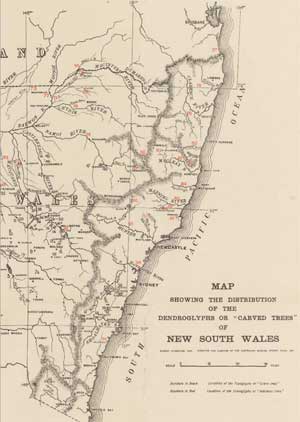

Central and western NSW were once dotted with sacred, carved trees, particularly regions such as Gamilaroi country (an area that stretches from the Upper Hunter Valley west to the Warrumbungle Mountains and north into south-west Queensland) and Wiradjuri country (a region bordered by the Lachlan, Macquarie and Murrumbidgee rivers). In these areas carvings marked the burial sites of important men and served as powerful initiation symbols for boys making their transition to manhood.

In Molong, four trees that were carved in the 1850s still surround the burial site of Yuranigh, a Wiradjuri man who was a guide to explorer Sir Thomas Mitchell. Sadly, this is a rare exception. In most other cases the plight of the carved trees is tightly bound to the dispossession of Aboriginal peoples after European colonisation.

"The last recorded ceremonies took place at least 100 years ago, around the time that Aboriginal people were moved into reserves and were rewarded for practising European ways and encouraged to accept European-style funerals and tombstones instead of trees," Ronald says.

Most of the 7500-odd sacred tree sites recorded in NSW have been destroyed by land clearing, bush fires, farming and natural decay. Today, Collymongle in north-west NSW, is the site of around 60 surviving carved trees, the greatest cluster remaining in the state.

More than a century ago, anthropologists such as Clifton Cappie Towle, Lindsay Black, Russell Black and Edmund Milne travelled around rural NSW in search of Aboriginal relics. They wanted to preserve indigenous heritage for the future and took hundreds of photographs to document what they found.

Lindsay Black reportedly travelled for miles along the Darling River, and trekked along its tributaries and creeks in search of tree carvings to capture on film.

During the 1930s and '40s many anthropologists also campaigned to save the remaining trees by collecting them and sending them to museums. "It's sad they were removed and put into museums, but that's also a good thing," Ronald says, adding that it's likely they would have been destroyed had they not been preserved in the right conditions.

Many of the trees ended up in museum storage, and now some communities are trying to get them back. Last year, Museum Victoria returned a carved tree to the Baradine community in north-west NSW that had been removed 90 years earlier. The tree was carved in 1876 to mark the burial site of five Gamilaroi men.

Larraine Ransfield, CEO of the Baradine Local Aboriginal Land Council, says the community was thrilled and welcomed the return of the tree with a smoking ceremony. "We were very proud seeing something so old come back to the community," she says. "There's not a lot of heritage like that."

Already the tree has attracted tourists, and has inspired other small communities to claim their carved trees back. Warren Macquarie Aboriginal Land Council is currently in dialogue with Museum Victoria to get two carved trees repatriated.

Carved Trees: Aboriginal cultures of western NSW is a free exhibition on display at the State Library of NSW until 26 June. The exhibition will then travel to regional NSW. Visit www.sl.nsw.gov.au for more information.

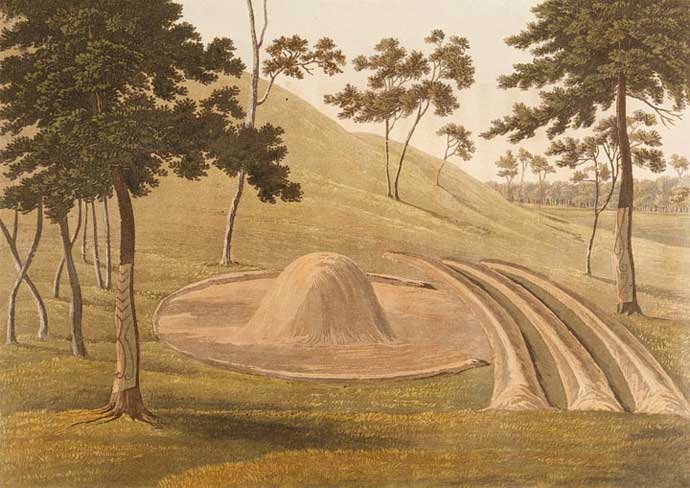

Grave of a Wiradjuri man at Gobothery Hill, near Condobolin, 1817

GE Evans

Journals of two expeditions into the interior of New South Wales, undertaken by order

of the British government in the years 1817–18, London: John Murray

DL Q82/74

To the west and north of the grave were two cypress-trees distant between fifty and sixty feet; the sides towards the tomb were barked, and curious characters deeply cut upon them, in a manner which, considering the tools they possess, must have been a work of great labour and time.

When Oxley published his journals in 1820, he included a drawing of the Gobothery grave site by GE Evans.

(State Library of NSW)

Aboriginal Arboglyph, one of four trees carved by the Boree tribe on the death of Yaranigh 1847 a3525001 - Image cropped - full size image in Powerpoint presentation

(State Library of NSW)

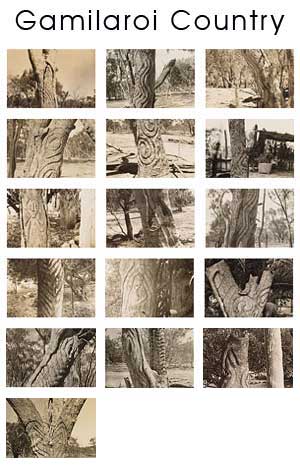

The Gamilaroi people in the central north-west designed their tree carvings around powerful symbols used for boys being ushered into manhood at elaborate ceremonies called Bora. Elders who were medicine men (Wirringan) and wizards (Koradji) instigated the Bora. During the ceremony boys - lead from one circle to the other and forbidden to look at the carved trees - were instructed on the significance of each symbolic design. Later, the boys were taken away from the Bora ground, away from mothers and other relatives, and provided with further instruction on manhood.

Gamilaroi country extends from the Upper Hunter Valley through to the Warrumbungle Mountains in the west and up through the present-day centres of Coonabarabran, Quirindi, Tamworth, Narrabri, Walgett, Moree and Mungindi in NSW, and to Nindigully in south-west Queensland. These photos from the Clifton Cappie Towle collection have been selected to illustrate the four basic styles of carvings: curvilinear lines, chevrons, figurative images and scrolls or circles.

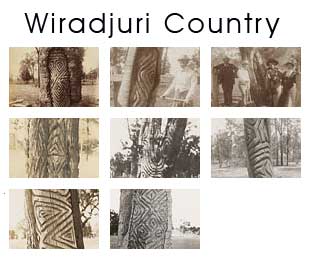

The Wiradjuri people of central NSW carved complex designs into trees to mark the burial site of a celebrated man whose passing had a devastating effect on the community. The designs may have been associated with the culture heroes admired by the man in life and were thought to provide a pathway for his spirit to return to the sky world. Usually only one tree was carved at each burial site, but as many as five have been recorded. The design always faces the grave, serving as a warning to passers-by of the spiritual significance of the area.

![]() Carved Trees Feature - The Australian Museum Magazine - 1940 pdf

Carved Trees Feature - The Australian Museum Magazine - 1940 pdf

All images accessible from thumbnail display were accessed from the State Library of New South Wales - Note the Reference Number when viewing images in the lightbox to match its description

[1], [2], [3], [15], [16] Bora Ground at Banaway [Collymongle], near Mogil Mogil, NSW, c. 1930s-1941

Russell Black - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol. 5

Comments: The most frequent type of carving found on the trees is based on curvilinear lines, although there are many variations. Some carvings are as simple as parallel wavy lines only, while wavy lines connect to enclose lozenge shapes with others. More complex carvings consist of curvilinear lines meandering over the trunk. In many cases the carving extends up the trunk of the tree well above head height. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[4], [5], [6], [11], [12] Bora Ground at Banaway [Collymongle], near Mogil Mogil, NSW, c. 1930s-1941

Russell Black - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol. 5

Comments: Many motifs are based on spirals or scrolls and concentric circles. The scroll or spiral designs are the boldest and the most dynamic. These large-scale designs fit the natural shape of the tree beautifully and are perhaps the finest examples of Gamilaroi artistic expression. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[7], [8], [9] Bora Ground at Banaway [Collymongle], near Mogil Mogil, NSW, c. 1930s-1941

Russell Black - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol. 5

Comments: Amongst all the carved trees, very few have figurative images and there are only two images of human figures. One appears to be wearing a skirt and the other is a silhouette, possibly created when figures were cut from the bark of trees to be used elsewhere in the bora rite. Snakes, boomerangs and spears are also depicted. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[10], [13], [14] Bora Ground at Banaway [Collymongle], near Mogil Mogil, NSW, c. 1930s-1941

Russell Black - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol. 5

Comments: A small number of trees are distinguished by simple, deeply-carved chevrons or V-shaped designs. The massive forked tree in these photos shows one fork with chevrons and the other with the curvilinear lozenge design. The amount of regrowth seen on this tree attests to its great age. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[17] Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: A remarkable example of a carved burial tree from the Dubbo district, NSW. This photo was taken in the early 1900s before it was removed and taken to the Australian Museum. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[18] Photographs of Edmund Milne standing next to Aboriginal Arborglyphs [carved trees], Gamboola, near Molong, 1912

Photographer unknown - SPF / 1149 (Source: State Library of NSW)

[19] Photographs of Edmund Milne standing next to Aboriginal Arborglyphs [carved trees], Gamboola, near Molong, 1912

Photographer unknown - SPF / 1150

Comments: Yuranigh was a Wiradjuri man from the Molong district who befriended Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell on his 1845 expedition into central Queensland. When Yuranigh died in 1850, four trees were carved to mark his burial site. Mitchell later paid to have a headstone erected over the grave. Today Yuranigh's grave remains as the only example of a grave with traditional Aboriginal and European monuments.

- These photos show amateur anthropologist Edmund Milne and a group of friends on a site visit in 1912. (Source: State Library of NSW)

[20] Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: Burroway, near Narromine, NSW (Source: State Library of NSW)

[21] Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: Woodlands Station, near Narromine, NSW (Source: State Library of NSW)

[22} Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection -PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: Ewanmar Creek, near Dubbo, NSW (Source: State Library of NSW)

[23] Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: Carved tree near Narromine, NSW (Source: State Library of NSW)

[24] Photographs of Aboriginal rock art and stencil art, stone tools and landscapes, c. 1925-1944

CC (Clifton Cappie) Towle - CC Towle collection - PXE 1018 / vol.11

Comments: Near Bulgandramine, NSW (Source: State Library of NSW)

The main text on the page is by Natalie Muller, previously published in the Australian Geographic on 6 June 2011 - Sovereign union added further files and images accessed from the State Library of NSW website and some other online research. Both the writer and the Museum did a service to us for presenting the general information, however, once again it is presented as a feel good story, trying to hide the underlying genocide, the desecration of peoples, their culture and the land. Their works also eliminate the important cultural protocols of tribal practices.