The Brutal Truth - What happened in the gulf country NT

When you know who owned the stations on which Aboriginals were killed and the names of the politicians who knowingly allowed it all to happen, you also know the Who's Who of colonial Australia. It is horrific to read, in fine detail, what was done to hundreds of innocent men, women and children. That is why some people still want this history to remain hidden.

Tony Roberts 'The Monthly Essays' November 2009

In the last six months, my curiosity about the extent to which governments in Adelaide condoned or turned a blind eye to frontier massacres in the Gulf Country of the Northern Territory, up until 1910, has led me to fresh evidence that has shocked me. It has unsettled the world I thought I knew. I was born in Adelaide, a fourth-generation South Australian, and have resided there for much of my life. The city's cathedrals and fine old buildings are very familiar to me. When I was young, I heard or read in newspapers the names of the old and powerful families, but took little notice. Even now, I feel uneasy revealing all that I have uncovered.

In 1881, a massive pastoral boom commenced in the top half of the Northern Territory, administered by the colonial government in Adelaide.1 Elsey Station on the Roper River - romanticised in Jeannie Gunn's We of the Never Never - was the first to be established. These were huge stations, with an average size of almost 16,000 square kilometres. By the end of the year the entire Gulf district (an area the size of Victoria, which accounted for a quarter of the Territory's pastoral country) had been leased to just 14 landholders, all but two of whom were wealthy businessmen and investors from the eastern colonies.2

Elsey Station was the third station in the NT to be taken up. Its first owner was Abraham Wallace in 1880.

Image: The original Elsey Station House 1907

Source: South Australian History website

National Library of Australia

Once they had taken up their lease, landholders had only three years to comply with a minimum stocking rate. By mid-1885 all 14 stations were declared stocked. What happened in the course of this rapid settlement is the subject of this essay. At least 600 men, women, children and babies, or about one-sixth of the population, were killed in the Gulf Country to 1910. The death toll could easily be as high as seven or eight hundred.3 Yet, no one was charged with these murders. By contrast, there were 20 white deaths, and not a single white woman or child was harmed in any way. The South Australian government of Sir John Cox Bray (1881-84) knew from a variety of reports that the region was heavily populated.4 And it knew, from experience in South Australia over the preceding 45 years, precisely what the consequences of wholesale pastoral settlement would be: starvation, sickness, degradation and massacre.5

There was no regard for the legal and human rights of the Aboriginal owners of the land: no explanations, no consultations. In just four years, the Aboriginal population of at least 4000, composed of 15 tribes or language groups, was dispossessed of every inch of land.6 Profound cultural and emotional consequences flowed from this, made more acute by the complex spiritual link that traditional Aboriginal people have with their country.7 Compared with more than 35,000 years of occupation, four years must have seemed like the blink of an eye.

There is a peculiar dimension to this tragedy. The pastoral industry, for which the government had been willing to sacrifice hundreds of lives and dispossess thousands of people, was a failure. Six of the 14 stations were abandoned within ten years, others changed hands and nearly all were greatly reduced in size.

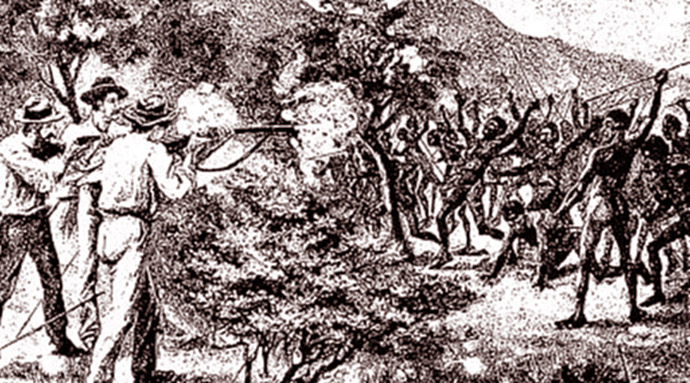

The bland phrase 'frontier violence' conveys little of the horrors inflicted. Even before the Gulf leases were granted, there were pitched battles. Massacres started on the Coast Track in 1872 when overlanders began passing through with cattle and horses. A member of the first party described in a long article for the Brisbane Courier the "deadly effect, even at 350 and 400 yards" of their state-of-the-art rifles, adding: "still the blacks showed a bold front, and were not driven back without an obstinate resistance".8 Further on, at the Cox River near Limmen Bight, they encountered a large number of people painted for ceremonies.

A History of the Gulf Country to 1900

Again they fired from a distance, yet "for nearly a full half-hour [the original inhabitants] held their ground in the face of strange weapons, of whose deadliness they received, momentarily, fearful proofs in the numbers of their comrades who writhed or lay forever motionless."

After surrendering, and with their weapons placed on a fire and burnt, "the blacks engaged in tending to their wounded. Some tore from the tea trees strips of bark for bandages, while others came up to the fire and got pieces of broken spears to serve as splints for the shattered limbs of the sufferers." Encounters like these on the Coast Track continued for the next 15 years.9 During the Kimberley gold rush of 1886, prospectors and overlanders "shot the blacks down like crows all along the route", according to the Northern Territory judge Charles Dashwood.10 Some travellers shot Aboriginals† for sport; others had heard of the "warlike savages" west of the border and shot them on sight out of fear.

Much early frontier violence in the Territory took the form of punitive expeditions, which were the reflex reaction to the spearing of cattle and horses or attacks upon whites (which were themselves often in retaliation for the shootings or abductions of women and girls). Their purpose was to both "punish" the local tribe and "teach them a lesson".

In the language of the north Australian frontier, "a severe lesson" or "a lesson they will never forget" meant wholesale slaughter. Punishment also involved wanton destruction. After slaughtering the occupants of a camp, the police and others would burn the bodies, homes, weapons and canoes, and shoot the dogs.11

Image source: 'Australia Twice Traversed' - The Romance of Exploration, Five Exploring Expeditions into and through Central South Australia, and Western Australia,

From 1872 to 1876. (Image cropped)

Here is one case typical of the punitive expeditions. On 30 June 1875 at the Roper River, a telegraph worker from Daly Waters had been killed, and his two mates badly wounded, probably by Mangarrayi men.12As a consequence, Aboriginals along the length of the river were slaughtered by a massive party of police and civilians for four weeks solid in August 1875.13 Although the orders came from Inspector Paul Foelsche, the government's attack dog in Darwin, an operation of such size and cost, with a blaze of publicity, would have required approval from the government of Premier Sir James Penn Boucaut.14 Foelsche issued these cryptic, but sinister, instructions: "I cannot give you orders to shoot all natives you come across, but circumstances may occur for which I cannot provide definite instructions.”15 Roper River blacks had to be "punished”. Foelsche wanted to go with them, but it was a large party, he said, with "too many tale-tellers”. He boasted in a letter to a friend, John Lewis, that he had sent his second-in-command, Corporal George Montagu, down to the Roper to "have a picnic with the natives”.16 Even the normally enthusiastic Northern Territory Times was sickened by "the indiscriminate 'hunting' of the natives there”, adding "there ought to be a show of reason in the measure of vengeance dealt out to them.”17 Seven days earlier, the paper's response to the death of a prospector in Arnhem Land had not been so mild: "Shoot those you cannot get at and hang those that you do catch on the nearest tree as an example to the rest.”

C H Johnston marker, Photo: Jum Gayton

Northern Territory Library

Three years later, in January 1878 (when Boucaut was again premier), Foelsche dispatched a punitive party to Pine Creek, under Constable William Stretton, after a teamster was murdered. Seventeen Aboriginals were shot by Stretton's men and an unknown number were shot by a civilian party.

18 In another revealing letter to Lewis, Foelsche referred to this as "our Nigger Hunt”. He said he should have gone himself, but "could not have done better than [Stretton] did, so I am satisfied and so is the public here”.19 In a further letter he observed: "By the majority of the population here, the Aborigines are looked upon as beasts, destitute of reason and are treated as such.” Like the earlier Roper River expedition, those at Pine Creek were well publicised in the Territory press, suggesting that Foelsche again had official approval.20

A month after this, secret fresh instructions were issued to Territory police as a result of public unease in Adelaide over the Pine Creek massacres, but the government covered its backside by attaching tissue-thin conditions. The law could be ignored by police and civilian punitive parties if the shooting was in "self-defence” - an old excuse on the frontier - or if there was "fair evidence” that the victims were part of the guilty tribe and their "resistance” made capture impossible. The policy of punishment, rather than arrest and trial, was re-affirmed. Premier Boucaut, a former attorney-general in three ministries, had referred the matter to Attorney-General Charles Mann "for his consideration and advice to cabinet”. Mann decided it was "utterly out of the question” for Aboriginals to be treated "as if they were civilized”, and concluded his advice with the astonishing observation, "the case is hardly one of 'law' but essentially of policy.”21 The Boucaut ministry of six agreed, as did successive governments. The policy of state-sanctioned slaughter continued for another 32 years. Months after this decision, Boucaut was appointed to the Supreme Court.

In the Gulf Country, pastoral settlement in the early 1880s was accompanied by massacres that occurred across the entire district for the next 30 years and beyond. Only two of the 14 stations had a policy of not shooting the blacks: Eva Downs Station, managed by Thomas Traine, and Walhallow Downs Station, managed by John Christian, both from New South Wales. These were smaller stations and the only ones not owned by wealthy investors.22

Punitive expeditions could also arise from Aboriginal behaviour considered cheeky or impertinent. On a number of stations, the land was simply cleared of "wild blacks”, so the cattle would not be disturbed at the waterholes and stockmen would not be at risk of attack.23 Some whites had a grudge against Aboriginal people, because they - or one of their family members - had been attacked in the past, so they shot them on sight.24 There were attacks upon large groups painted for ceremonies; these were often described as "weird war dances” and the markings characterised as "war paint”. One such attack occurred at McPherson Creek, near the Wearyan River, where a number of local tribes had gathered for the a-Kunabibi ceremony. Pyro Dirdiyalma lost his grandfathers and his father's brothers in this massacre: "From the south those men came on horseback and shot them, for no reason they shot them, all of them, they were all dead. They then burnt them all, they burnt them until there was nothing but ashes. They killed all the old rainmakers, all the men of the Wawukarriya country.” Severe droughts in the 1890s were attributed to the loss of these old rainmakers.25

Ted Lenehan, a stockman on McArthur River Station, was out hunting blacks in March 1886 when he was ambushed and killed.26 The dismemberment of his body was a practice reserved by the Ngarnji tribe for particularly violent men, to prevent their spirit from continuing to perform evil deeds. Sir John Cockburn, minister for the Northern Territory in the Downer government, ordered Constable William Curtis and five native police based at the Roper River to "investigate”.27 On arrival at the station, they were joined by the manager, Tom Lynott, and 15 stockmen, including the notorious Tommy Campbell, the so-called "half-caste” Queenslander who allegedly shot more blacks in the district than any white man. There were also Aboriginal stockmen from Queensland, whose tracking skills were invaluable.

One of the massacres that followed occurred on top of the Abner Range, a hundred kilometres from where Lenehan had been killed. After picking up the fresh tracks of about 70 or 80 fleeing Aboriginals, the party of 22 galloped after them. The blacks were travelling so fast that some of the old ladies couldn't keep up and were left behind. Charley Gaunt, one of the white stockmen, later wrote a detailed account of what happened, but was silent on whether the old ladies were shot.28

Six years later, in 1892, there was no uncertainty. During another pursuit by police and stockmen on the Barkly Tableland, the old ladies who fell behind were shot by Tommy Campbell. Thinking the Abner Range would be impossible for horses, the fleeing group reached the top, where it was flat and sandy, and slowed down. They began hunting for food. But the horsemen found a way to the top and it was a simple matter to follow the tracks. Knowing the blacks were not far ahead, they set up a base camp at a spring and left all the horses except the ones they were riding. Then, they rode cautiously on until dark, made camp and waited. Next morning, long before dawn, they set off quietly on foot - bootless - leaving an Aboriginal to guard the horses. When they saw the fires of the sleeping camp in the distance, it was still dark. This clinical description of what followed provides a rare insight into frontier massacre.

The men, in pairs, formed a half-circle around the sleeping camp - some of them as close as 20 metres. On the far side of the camp was a sheer, 150-metre drop. The numerous small fires were evidence of a large number of people. Curtis said he would fire first, as soon as it was light enough to see. Shooting sleeping victims at first light was a standard method. Exhausted, the occupants of the camp slept soundly. But, at times, according to Gaunt, "we could hear a piccaninny cry and the lubra crooning to it.” When it was finally light enough to see, an Aboriginal man sat up and stretched his arms.

Smith fired and the police boy with me fired at the sitting Abo. The black bounced off the ground and fell over into the fire, stone dead. Then pande-monium started. Blacks were rushing to all points only to be driven back with a deadly fire … One big Abo, over six feet, rushed toward the boy and I. I dropped him in his tracks with a well-directed shot. Later on, when we went through the camp to count the dead and despatch the wounded, I walked over to this big Abo and was astonished to find, instead of a buck, that it was a splendidly built young lubra about, I should judge, sixteen or eighteen years of age. The bullet had struck her on the bridge of the nose and penetrated to the brain. She never knew what hit her … When the melee was over we counted fifty-two dead and mortally wounded. For mercy's sake, we despatched the wounded. Twelve more we found at the foot of the cliff fearfully mangled.

Below the cliff was the head of a creek, which Tom Lynott named Malakoff Creek, after a bloody battle during the siege of Sevastopol in the Crimean War.29 When a camp was attacked in daylight, the whites were usually mounted and, unless the country was open and flat, it was often possible for a number of occupants to escape. In some cases they watched in horror, unseen, as whites dispatched the wounded. Adults and children received a bullet to the brain, while babies - whether injured or not - were held by the ankles "just like goanna”, their skulls smashed against trees or rocks.30 A crying baby left behind when Garrwa people fled a camp on the Robinson River was thrown onto the hot coals of a cooking fire, still crying.31

On Vanderlin Island, in Yanyuwa country - where there were no cattle and no resident whites - people were shot on the coast for sport.32 According to one of several reliable and detailed accounts, a large boat arrived at a place called Mundakarrumba, on the west coast of the island, probably in the 1880s. Many people were camped by a lagoon close to the beach. Among them were Murruwaru and his adult sons, Babarramila and 'Vanderlin Jack' Rakuwurlma. There must have been smoke from cooking fires; men came ashore with guns. All the Aboriginals ran into the bush, except for a heavily pregnant young woman, who climbed a tree and hid in the canopy. She watched in terror as the white men stood under this tree, talking in a strange language. One of them looked up, saw her, called out to his mates. They all looked up and laughed. When the laughing stopped, one of the men raised his rifle and shot her. She fell to the ground dead.33

Today, elderly Yanyuwa people still ask me, "Why?” How can I tell my old friends their people were shot for sport, one hundred years after the First Fleet?

I have come to know many Aboriginal people from this district. My fascination with the early history of Borroloola - the only town in the Gulf Country - began in the late 1960s, long before I knew about Charley Havey. This cattleman, storekeeper and magistrate lived near Borroloola from 1906; he turned out to be my great-grandfather's brother. When I went on a trip in 1996 to gather information about Havey and others from the last of the old-timers, a neatly dressed elderly Aboriginal man named Whylo came to my camp and told me Havey had "grown him up” from the age of about five or six and had taught him stock work. This had been arranged by Havey and Whylo's father, 'Banjo' Dindhali, a traditional owner of Vanderlin Island. Dindhali proved to be the eldest son of the legendary 'Vanderlin Jack' Rakuwurlma. I asked Whylo whether he was there when Havey was evacuated by plane in 1950, close to death, and he replied, "Yes, I kissed him goodbye.”

So began a remarkable relationship, which soon extended to other Aboriginal families, initially because of their respect for my unknown uncle and, later, their interest in my study of Gulf history - their history. Archival material has added a new dimension to Aboriginal people's knowledge of the events of the past in the area. They knew what had happened to their people, but were stunned to learn that similar violence was repeated throughout the Gulf Country, and indeed the Territory.

There were massacres in which camps were attacked by day. There was slaughter involving men and women being shot at dawn while they slept, or lined up and shot, or cornered in a cave and shot.34 Men were shot in cold blood so their wives could be raped.35 Women were abducted and held prisoner for years or shot for sport. Girls as young as seven were raped by men with syphilis. Pastoral settlement was enforced with what must have seemed to Aboriginal people like weapons of astonishing power.

Most popular were the .57-calibre Snider rifle, designed for big-game hunting in Africa, and the more advanced, more powerful .45-calibre Martini-Henry. Both were used by the British army, yet almost every overlander, stockman and station manager had one or the other - and not for hunting kangaroos.

Northern Territory police were armed initially with Snider rifles, but by the time pastoral settlement in the Gulf Country began in 1881, these had been replaced by the Martini-Henry. The enormous bullets caused horrific injuries to those not killed outright. If fired into a crowd, a single bullet could pass through one person and kill or maim others. The Martini-Henry could kill at more than one kilometre. Both weapons could kill an elephant.

Why would a police force need military rifles that could kill elephants? The primary role of the police was not to maintain law and order but to make the Territory safe for whites and their cattle, regardless of the cost to Aboriginal welfare and life. They were an avenging force, acting as judge, jury and executioner. Successive governments issued the police with unlimited ammunition and the authority to use it; they also issued arms to civilian punitive parties.

They kept sending the ammunition in massive quantities to the Territory, knowing it was being used for a single function: to shoot the blacks. They asked no questions, did no stocktakes, took no count of the dead. If Aboriginal people resisted the taking of their land or resented the taking of their women or speared cattle for food, they became the sworn enemy. There is evidence of at least 50 massacres in the Gulf Country of the Territory up to 1910.36 It is impossible to estimate how many more went unrecorded; the real figure could well be double that.

When you know who owned the stations on which Aboriginals were killed and the names of the politicians who knowingly allowed it all to happen, you also know the Who's Who of colonial Australia. It is horrific to read, in fine detail, what was done to hundreds of innocent men, women and children. That is why some people still want this history to remain hidden.

The same names recur again and again. Sir John Cockburn, the minister for the Northern Territory in 1886, dispatched the police party that led the slaughter at Malakoff Creek: there was a death toll of 64 men, women and children in one camp alone, part of a campaign to kill all the "wild blacks” on the station. Cockburn became premier in 1889 and was later associated with Arafura Station in eastern Arnhem Land, which employed two gangs of men to shoot Aboriginals on sight from 1903.37

Source: National Library of Australia

Sir Richard Baker, a former attorney-general and chairman of the elite Adelaide Club, was minister for justice and minister for the Northern Territory in the Colton government of 1884-85. Baker personally approved the dispatch of four private punitive parties in 1884, following the murder of four copper miners at Daly River. He authorised the government resident (the top official in Darwin, who reported to the minister for the Territory), John Langdon Parsons, to issue the parties with government rifles and ammunition, and agreed to the extraordinary condition that no police accompany them.38 A huge police party was dispatched separately, under the notorious Corporal Montagu. The Northern Territory Times reported: "Orders have been given to bury the remains of the natives.” In other words, bury the evidence.39

Sir John Cox Bray was attorney-general in the Colton government of 1876-77, a time when Aboriginal people were being shot on stations near Cooper Creek and elsewhere in South Australia's far north. As premier (1881-84), Bray watched the rapid, callous dispossession of the entire Gulf population. He issued no rations for the hungry, he took no action to prevent the predictable massacres that followed and he laid no charges against those who committed mass murder.

Sir John Downer, one of the founding fathers of Australian federation, was equally complicit in all this. An examination of the injustices and massacres of the frontier period reveals his name more frequently than any other Adelaide politician. His role is worth considering in detail.

As attorney-general in the Bray government, Downer ignored a profoundly important clause in the pastoral leases - one that remains, with very minor amendments, to this day - that guaranteed Aboriginal people "full and free” access to the whole of the leased land and natural waters, the right to hunt wildlife for food and the right to erect "wurlies and other dwellings” as usual, as if the lease had not been granted. Its purpose was to mitigate the consequences of dispossession and prevent starvation.40 Downer could have changed the course of pastoral settlement in the Territory and saved many hundreds of lives had he upheld the law; instead, his illegal policy set the pattern.

Weeks after becoming attorney-general, Downer received an unusual request from Inspector Foelsche, dated 2 July 1881. Three drovers had been killed in unclear circumstances on the Coast Track in the Limmen Bight area over the course of the previous three years. Dozens of Aboriginal deaths had occurred there in the same period.

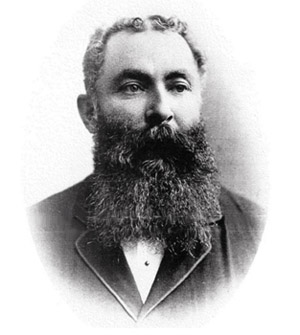

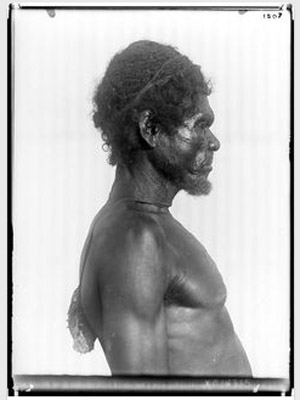

Inspector Paul Heinrich Matthias Foelsche

Inspector Paul Heinrich Matthias Foelsche asked the government for immunity from prosecution for his men, so they might slaughter sufficient numbers of the Aboriginals to teach them "a severe lesson"

Source: South Australian History website

Foelsche complained that "the dread of police is unknown” down there. This was a most telling remark. He asked the government for immunity from prosecution for his men, so they might slaughter sufficient numbers of the locals to teach them "a severe lesson”. He said he wanted to "inflict severe chastisement if the government will legalise it” and to "punish the guilty tribe without trying to arrest the murderers”.41 His boss, the government resident, agreed with him. Foelsche was clearly planning wholesale slaughter. The minister for the Northern Territory, John Langdon Parsons, a former Baptist minister, eventually conveyed the message that nothing could be done but took no steps to reprimand Foelsche or his boss. It is inconceivable that such an extraordinary request would not have reached the desk of Attorney-General Downer but he did nothing to restrain Foelsche or to revoke the existing policy. Foelsche learned not to seek prior approval in future, and successive governments continued to ask no questions.

There were dozens of massacres in the Gulf Country while Downer was attorney-general (1881-84) and both premier and attorney-general (1885-87). Had he taken steps to prevent them or to prosecute those responsible, many lives could have been saved. In 1885, for example, Downer ignored a detailed report tabled in the parliament that warned Aboriginal people were facing extinction.

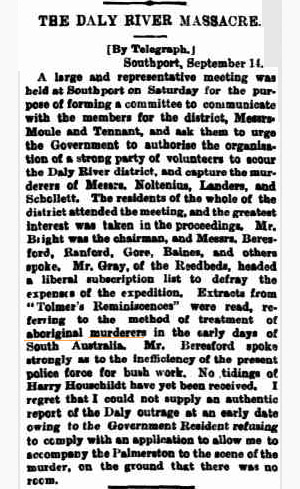

The South Australian Advertiser

Monday 15 September 1884

According to Parsons, now the government resident, violence on the Territory frontier was worsening. Parsons was shaken by the wholesale slaughter that had occurred around the Daly River in 1884, which he had facilitated. He urged for "a strong sense of justice and consideration for the natives”. He then went on to say that "even those who don't claim to be philanthropists” are concerned by the prospect of the blacks being exterminated "off the face of the earth”.42 Parsons' chilling report was tabled on 4 June 1885. The Downer government took office 12 days later, but ignored it: government policy remained the same. Incredibly, Downer took no action against those who took part in the 1884 massacres, despite some of the names being published in the Territory press.43

In June 1885, the South Australian Register published a long letter from Dr Robert Morice, the Territory's colonial surgeon and protector of Aboriginals, revealing the extraordinary geographical range of the massacres.44 They stretched from Southport, 30 kilometres south of Darwin, to the Daly River, a further 100 kilometres to the south, and across to the Mary River - which today forms the boundary of Kakadu Park. Morice said it was difficult to say how many had been killed altogether, but added: "I should say not less than 150, a great part of these women and children.” Modern estimates put the figure at well over 200. Morice was sharply critical of former premier Colton - a Methodist lay preacher, a "pious Christian … and member of the Aborigines' Protection Society” - whom he described as a hypocrite for his role in the massacres and the cover-up. Colton issued denials.

But, in Adelaide, there was growing public disbelief and outrage. Upon taking office, Downer did nothing in response to Morice's letter, hoping the public would never learn the terrible truth. But he knew, and so did Colton. They had kept - from the parliament and the people - a secret, self-incriminating report from Corporal Montagu, leader of the police party, dated 17 October 1884. As it happened, the South Australian Register got hold of the report and published a scathing editorial on 14 November 1885: "Down in South Australia good men try to civilize them with the Bible: elsewhere we civilize them with the Martini-Henry rifle.” It referred to "the cold-blooded manner” in which Montagu's men slaughtered the blacks, calling it "a butchering expedition”. The Northern Territory Times, owned by Vaiben Solomon, replied to this charge, arguing that Montagu had taken "the only rational method of dealing with blood-thirsty savages”.45 Solomon was another member of the Adelaide establishment: his father had been a member of parliament and lord mayor of Adelaide.46 Downer was now forced to table the report, but he continued to stonewall. His minister for the Territory, Sir John Cockburn, tried to defend Montagu.

It was another case of the establishment closing ranks. Downer and his fellow politicians needed to maintain the pretence that blacks were only shot in self-defence. The South Australian Register observed: "The perpetrators are not only those who shot down the wretched blacks, but the officials who authorized and concealed this disgraceful deed.”47 Forced by increasing public criticism and a fear of losing office, Downer appointed a board of inquiry in December, but he still had a few more tricks up his sleeve. Murder charges and a sensational trial could end political careers and ruin reputations; the knighthood he was anxiously seeking might slip away. Downer orchestrated a breathtaking whitewash. Instead of being held in public, it would be a private inquiry, with no notice of hearings. Only selected persons were to be interviewed (and certainly not Dr Morice) and the inquiry would examine only the police involvement (yet there were also four civilian parties). Downer appointed businessman Arthur Baines as chairman; Baines had ridden with one of the civilian punitive parties and had used a rifle and ammunition supplied by the government. Another board member was Hildebrand Stevens, the son-in-law of Foelsche and the Territory manager of the pastoral stations on which the worst of the massacres took place (Daly River Station and Marrakai Station).48 Unsurprisingly, the board unanimously found that the Aboriginals were treated with leniency and there was "no evidence … that slaughter or cruelty was practised by the police”.49

In 1891, Downer again played a part in preventing a conviction for frontier murder. The notorious Constable William Willshire - after a decade of murdering and raping Aboriginals in Central Australia - was finally charged with two murders committed at Tempe Downs Station by the humanitarian justice of the peace Francis Gillen (of Spencer and Gillen fame) in Alice Springs. If Willshire was convicted, the dominoes would fall. It was not only his boss, Inspector Brian Besley of Port Augusta, and the police commissioner, William Peterswald, who were vulnerable. So, too, were the premiers who had known of Willshire's methods and had chosen to look the other way: Bray, Colton, Downer, Playford and Cockburn. Willshire would almost certainly have made it clear that, if he went down, he would take others with him: he was that type of person.

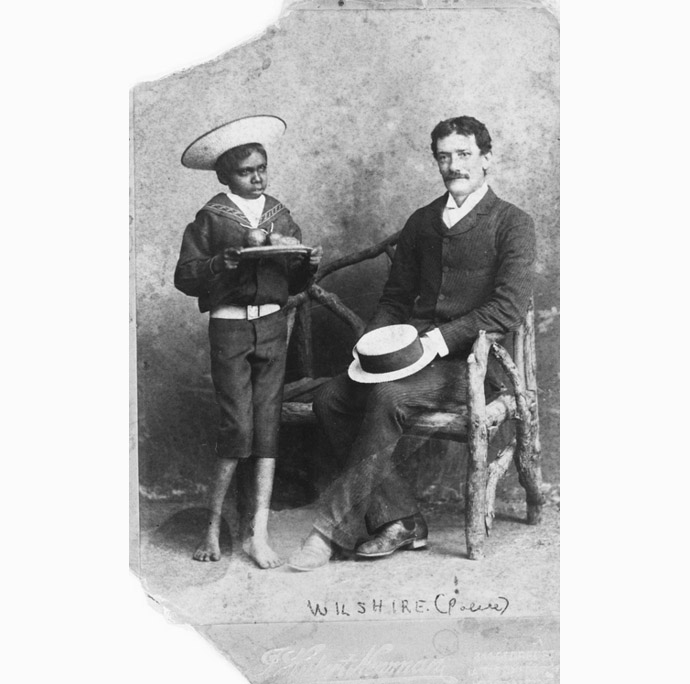

William Henry Willshire, 1852-1925, police officer, was born in 1852 in Adelaide, son of a schoolmaster. He joined the South Australian Police Force in 1878 and was posted to Alice Springs in 1882, and promoted to 'first-class' mounted constable in 1883. After a decade of murdering and raping Aboriginals in Central Australia he was finally charged with two murders. In a sham trial, held at Port Augusta he was allowed to question prosecution witnesses in Aranda and then to offer his own translations of their answers to the court. His acquittal was no surprise.

The establishment, again, closed ranks. The trial, held at Port Augusta (rather than Adelaide), was a sham. The Playford government presented a weak case and Sir John Downer acted for the defence. In his opening address the prosecutor sounded as if he was appearing for the defence and excuses for Willshire's behaviour were offered. The prosecutor denigrated his own Aboriginal witnesses: they showed "simplicity of character”; they possessed a "not too retentive” memory; they revealed a tendency to say what they thought the listener wanted to hear. Judge William Bundey, a former attorney-general and minister for the Territory, played his part. He allowed Willshire to question prosecution witnesses in Aranda and then to offer his own translations of their answers to the court. The acquittal was no surprise. A northern pastoralist wrote of the trial: "I was present and never heard a more one-sided affair.”50

In March 1893, after two years in country towns where he had been disciplined for being drunk, lying, insubordination, insolence and setting an "evil example to his comrades”, Willshire's behaviour was brought to the attention of Sir John Downer.51 By now, Downer was premier as well as chief secretary, with responsibility for the police and minister for the Territory. He transferred the known killer to the remote Victoria River District where "wild blacks” were spearing cattle. Willshire and his native constables were let loose with no supervision but with an endless supply of ammunition. For the next 16 months, based in a hut at Gordon Creek on Victoria River Downs Station, he slaughtered an unknown number of Aboriginals.52 In 1895, following a change of government, the minister for the Territory ordered Willshire's immediate return to South Australia, saying "he is the last man in the world who should be entrusted with duties which bring him in contact with the Aborigines.”53

Apart from Willshire, no white person was ever prosecuted in connection with the massive number of Aboriginal deaths on the pastoral frontier in the Northern Territory — likely to have been in excess of 3000 — during the period of South Australian administration to December 1910.54

Earlier, on the South Australian frontier, where the blacks were slaughtered for half a century, less than a handful of prosecutions were launched and none was successful.55

One must not imagine that the Territory's frontier violence was too far removed from Adelaide, or too secretive, for successive governments to have known about. Governments knew exactly what was going on. There were boastful accounts in the Darwin press, which would have been passed on by the government resident, whose quarterly reports were tabled in the parliament. In his report for the 1887 calendar year, Parsons described the escalating level of conflict on nearly all of the cattle stations. He then remarked: "It is an affectation of ignorance to pretend not to know that this is the condition of things” in the remote parts of the Territory.56 Successive governments ignored his warnings. Police procedures remained unchanged, the supply of ammunition kept flowing, the prosecutions never happened. Aboriginals kept dying; the trauma, suffering and psychological damage continued. Pastoralists called on ministers as they sought increased police resources to "punish the blacks” for spearing cattle, because responsibility for this "disagreeable duty”, as one pastoralist put it, should not be left to station managers and stockmen.

The man who masterminded more massacres in the Territory than anyone else was Inspector Foelsche. A former soldier, he was cunning, devious and merciless with Aboriginals, yet he was supported by every South Australian government from the founding of Darwin in 1870 until his retirement in 1904, when King Edward VII honoured him with the Imperial Service Order. Kaiser Wilhelm gave him a gold medal, possibly for the specimens and written material on Aboriginals he sent to museums in Germany. Some considered him an expert on Aboriginals, not knowing the skulls he studied were not merely collected by him.

Why does a river in the Gulf Country honour a man like Foelsche? Why does a street in Alice Springs honour Constable Willshire? Why is a suburb in the national capital named after John Downer? Why do streets there commemorate John Bray, John Colton, Richard Baker and John Cockburn? Must we rub the noses of Territory Aboriginals in this dark history? They were treated as expendable and earmarked for discreetly achieved extermination. In his inaugural Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture of 1996, Sir William Deane reminded us that Australia will remain a diminished nation until true reconciliation is achieved. It is plain to see why. The present plight of so many Aboriginal people, he said, flows largely from the dispossession, injustice and oppression of the past. Nowhere is that more evident today than in the Gulf Country of the Northern Territory.

† 'Aboriginal' is here used as a noun at Tony Roberts' request.

CPP Commonwealth Parliamentary Paper

NTAS Northern Territory Archives Service

NTT Northern Territory Times and Gazette

SAPP South Australian Parliamentary Paper

SRSA State Records of South Australia

1 This was triggered by favourable reports from explorers Ernest Favenc, who crossed the Barkly Tableland from Queensland (1878-79), and Alexander Forrest, who travelled through the Victoria River district from Western Australia (1879), and a reduction in pastoral rents. A similar boom soon followed in the Kimberley region.

2 For the purposes of this essay, the Gulf Country extends from the Queensland border in the east to the overland telegraph line (or Stuart Highway) in the west, and from the Roper River down to Tennant Creek. It includes the Barkly Tableland and comprises some 223,600 square kilometres or 17% of the Northern Territory. While the station sizes in Table 1 of Frontier Justice were taken from government pastoral records, modern mapping methods have revealed that the district and stations were larger than previously thought, giving an average station size of almost 16,000 square kilometres or 6,000 square miles. A map of station boundaries in 1885 is attached: it shows 15 stations but Valley of the Meadows was never formed as the owner died while the first mob of cattle were en route (the lease was forfeited and the land was used by neighbouring stations). The events described in endnote 31 occurred in the Valley of the Meadows area.

Map 1 (PDF): Station boundaries in 1885.

http://www.themonthly.com.au/files/Roberts-Map-1-OO.pdf

3 The estimate of at least 600 deaths is based on my extensive research of massacres on the pastoral frontier in the Northern Territory and north-west Queensland (where many of the NT station managers and stockmen worked before following the frontier westwards). More than 50 massacres are known to have occurred in the NT Gulf Country to 1900. A number of stations, including McArthur River, Hodgson Downs, Cresswell Downs and Calvert Downs had a policy of shooting Aboriginals on sight, sparing none. This, and the known brutality of particular men, such as D'arcy Uhr, Tom Lynott, John Mooney, Ted Lenehan, Tommy Campbell, Charley Gaunt, Dick Moore, Charley Scrutton and Jack Watson - all of whom took part in Gulf Country massacres - means that the death toll there must have been very high. A brief study of early massacres in the Gulf and elsewhere in the Territory gives a hint of the scale of frontier slaughter there. We know that a great many people - probably 150 or more - were killed along both sides of the Roper River in 1875, as described later in the essay; that at least 200 were killed near the Daly River in 1884; that 64 died in one camp alone on McArthur River Station in 1886 as part of a campaign to exterminate all "wild blacks” on the station; and that about 100 were killed in the Coniston massacres south-west of Tennant Creek in 1928. Police led, or participated in, all of these punitive expeditions. A single spear (causing no harm) thrown into Dick Moore's tent at night on the Calvert River in the late 1880s resulted in camp after camp of local people being wiped out over the following months. The only people to be spared were the young women Moore and his men abducted. Moore is alleged to have shot "bush blacks” on sight, once killing 13 while they were crossing a plain (Buchanan 1934: 76). The estimate of the Coniston death toll can be found in the Yurrkuru (Brookes Soak) Land Claim Report by Justice HW Olney, 10 April 1992, paragraph 6.1.5, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1992. Details of events and people not mentioned in this essay can be found in Roberts 2005.

4 In 1845, Ludwig Leichhardt followed a well-worn Aboriginal trade route, which ran parallel to the coast from the Nicholson River to the Roper River. We learn from his journal, published in 1847, that this country was home to a high concentration of people leading industrious lives. In the vicinity of what is now the Robinson and Wearyan Rivers he described emu traps around waterholes, fish traps and fishing weirs across rivers, well-used footpaths, major living areas with substantial dwellings, wells of clear water and a sophisticated method of detoxifying the otherwise extremely poisonous cycad nuts. This route would become the Coast Track. (Note that the names of Gulf rivers are different today from those Leichhardt uses in his journal.) Ernest Favenc provided detailed reports on the Barkly Tableland to the South Australian government and wrote a series of articles for the Queenslander in May and June 1879. At Corella Lagoon, he reported seeing some 300 "friendly” Aboriginals gathered for ceremonies. From 1872, when overlanders and prospectors began using the Coast Track (bound for Darwin), accounts of clashes with Aboriginals, as well as evidence of large populations along the entire route, must have reached officials in Darwin. From 1874 (and possibly earlier) detailed articles appeared regularly in Darwin, Adelaide and Brisbane newspapers. For example, George De Lautour's article, in which he described his journey of early 1874, remarking of the Calvert River, "the natives were very numerous here; but most friendly.” (NTT 5.12.1874)

5 Typical of the articles and letters appearing in the Adelaide press before pastoral settlement began in the Gulf Country is this, which was written in Penola in the south-east, where the winters are cold: "It is hardly creditable to the government that these poor people, who have been despoiled of their hunting grounds, should be left to shiver in the cold and die of starvation while the white population is reaping wealth from those very lands.” (South Australian Register 18.7.1878) At the very time it was issuing leases for the Gulf Country, the government was also issuing rations in South Australia. It had been doing this for decades, thanks to pressure from missionaries and other humanitarians. There were also Protectors of Aborigines in the south. But in the Gulf Country there were no ration depots, no protectors and, for the first five to seven years, no police officers to curb the excesses of station managers.

6 A map of Aboriginal language groups prior to European contact is attached. In Frontier Justice I used an extremely conservative estimate of "at least 2500” for the Aboriginal population (p. 96), a figure I increased to "at least 3000” for the Blackheath History Forum lecture of 29 August 2009 following further research. Now, in light of yet more credible material, from 1905 (concerning the Territory as a whole), I believe the Gulf population could not have been less than 4000 and that it was perhaps as high as 5000. During a visit to the Territory in 1905, Sir George Le Hunte, the governor of South Australia, sought estimates of the Aboriginal population. They ranged from 15,000 (from a government official) for the entire Territory to 30,000 (a private source); this gives an average of 22,500. The then recently retired Inspector Paul Foelsche thought the first figure too low and the second too high: he thought a safe estimate would be 20,000 to 22,000. (Extract in CPP 1909 vol. 2: 1913) Employing the figure of 22,000, it would be reasonable to add 15% to calculate the pre-contact population (which would allow deaths from violence and disease, as well as diminishing birth rates, to be accounted for), suggesting a figure of 25,300.

The Gulf Country is a mixture of fertile land on the coast and semi-arid land on the Barkly Tableland; this diversity makes it fairly representative (as a region as a whole) of the population per square kilometre of the entire Territory. On this basis the pre-contact population of the Gulf Country would have been in the order of 4300 (17% of 25,300). Another method can be used to verify this result. There were 15 language groups, each involving around 300 people, though part of the Warumungu and Yangman estates lay beyond the western boundary of the district, so I employ the notional figure of 14 language groups. If each of these involved 300 people, then the area must have had a population of 4200. In other words, it is safe to assume a pre-contact population for the Gulf Country of at least 4000. The actual figure may have been as high as 5000.

Map 2 (PDF): Aboriginal language groups as they existed prior to European contact.

7 For further details see Roberts 2005: 2-5.;

8 Brisbane Courier 27.10.1874. This incident occurred between the Wearyan and McArthur Rivers, possibly at McPherson Creek where large inter-tribal ceremonies were held. Aboriginal men had driven back the leading cattle, possibly out of fear that these strange beasts with horns growing out of their heads would harm the women and children. Old Yanyuwa people have described the fear caused by horses, which were thought to be giant dogs that might bite them. Also of concern was the fact that this overlanding party had taken "a little black boy” at the Wearyan River to act as their guide (Brisbane Courier 16.9.1874). When the shooting stopped, the party searched up and down the creek until they found an Aboriginal camp - presumably with a view to inflicting further casualties - but it was empty. They found "numerous bundles of spears, nulla-nullas and boomerangs which were quickly broken up and burnt”.

9 Famous in frontier literature and legend - because it was so difficult and dangerous, and saw the biggest cattle drives in our history - the Coast Track went for 1000 kilometres from Turn Off Lagoon to Katherine. There were crocodile-infested river crossings, long stretches of deep sand, poor grasses and attacks by Aboriginals. Despite the dangers, the vast cattle stations in the northern half of the Territory and the Kimberley were stocked largely from the eastern colonies via this route. By the end of 1885, when the stations were stocked and the flood of animals and men had subsided, more than 200,000 cattle, around 10,000 horses and countless heavy bullock-wagons had passed along this route. Then came the Kimberley gold rush of 1886 and prospectors in their hundreds followed the old tracks of the cattle. It was a momentous time in Australian history.

Watching in stunned disbelief were the Aboriginal owners of these various estates. Precious lagoons, the source of food and clean water, were fouled by cattle; living areas, fish traps and wildlife habitats were damaged or destroyed; and beasts became bogged and died in the shrinking waterholes of the dry season, turning them into slimy swamps.

Incredibly, body parts were stolen from corpses on funeral platforms and skeletal remains were taken from log coffins. The enormous herds began spilling out from the stock route and soon occupied the entire district. Sites of profound significance were desecrated. Now dispossessed, the tribes were forced to live secretly, hidden in the hills and gullies, at risk of being shot. The Wilangarra and Binbingka were among the coastal tribes that felt the full brunt of this extraordinary migration: both are now extinct. It was a momentous time in Aboriginal history.

A comprehensive history of the Coast Track can be found in Roberts 2005 pp. 1-67.

10 Select Committee of the Legislative Council, Minutes of Evidence on The Aborigines Bill 1899, question 516, 25 August 1899. Dashwood, the principal architect of the Bill, was referring to the entire route across the Territory to the Kimberley, and not just the Coast Track. He said that the shootings were particularly bad in the Victoria River district and went on to say (q. 517): "in many places in the Northern Territory it has been the practice of pastoralists to get black boys [i.e. men] from Queensland and arm them with rifles for the purpose of shooting down natives.” J Langdon Parsons, a former minister for the Northern Territory and government resident from 1884-90, was embarrassed by Dashwood's claims, as was Inspector Foelsche. He suggested that if such things had happened, Foelsche would surely have informed him, so Dashwood revealed his sources in a letter dated 23 March 1900, in SAPP 1900 vol. 3, no. 60: 2.

11 The burning of houses, weapons and canoes by police remained a common means of punishing and intimidating Aboriginal people, even after the frontier period. In 1902 the police from Borroloola sailed with trackers to South West Island hoping to arrest a Yanyuwa man named 'Carpenter' on a larceny charge. When others on the island refused to give him up, threatening to kill the tracker who suggested it, they were punished by having their ten canoes burnt. This left them with no means of hunting dugong or turtle, or travelling to the other islands. (NTAS F268, 22.11.1902). Camp dogs were still being shot or clubbed to death in the 1930s. In 1932, at Calvert Hills station, Constable Gordon Stott "destroyed seven Aboriginal dogs with a waddy”. Four days later, he shot 29 Aboriginal dogs at Wollogorang Station (NTAS F268, 22.12.1932, 26.12.1932).

12 NTT 17.7.1875.

13 NTT 24.7.1875, 18.9.1875; South Australian Register 14.10.1875. The attack took place at Roper Bar and the murdered man was Charles Johnston. One of his wounded companions, Charles Rickards, managed to write a note about what had happened, indicating that their attackers (some of whom they knew) were from Mole Hill about 75 kilometres upstream. Three weeks later, an overlanding party led by George De Lautour (a man of dubious character), en route to Queensland, found the note and slaughtered an unknown number of people at Mole Hill before burning their huts and weapons. When the official party of police and civilians arrived at Roper Bar on 2 August they found letters dated 19 and 24 July from one of De Lautour's men describing the punishment delivered. They also visited the remains of the Aboriginal camp and saw the dead bodies. A member of the official party later wrote that the overlanders "dispersed them thoroughly … [and] fully avenged Johnston's death” (NTT 18.9.1875).

After this, the official party set to work slaughtering Aboriginals on both sides of the river, upstream from Roper Bar. On 20 August, police reinforcements arrived on a government boat from Darwin and the slaughter continued downstream from the Bar, as far as the river mouth, notwithstanding that those tribes had nothing to do with Johnston's murder. The random killings extended along a 200 kilometre stretch that ran both north and south of the river.

When the boat departed, the land party returned to Mole Hill where, on 4 September, they shot more people. The total death toll is impossible to guess, but was likely in excess of 150 or 200.

14 Lending support to this view is the revelation in the Northern Territory Times of 17 July 1875 that the minister for the Northern Territory, Ebenezer Ward, and Superintendent of Telegraphs, Sir Charles Todd, sent telegrams to Darwin requesting that a punitive party be formed without delay. The Times praised "the promptness with which the Government have dispatched a party to the scene of the occurrence”. See also Reid 1990: 67 for Todd's involvement.

15 In fact, Foelsche's instructions went further: "All that can be identified as being of the attacking party are to be captured either dead or alive; the slightest resistance, attempt to resist, or assisting the guilty parties to escape must be met by prompt actions without waiting to be molested. I cannot give you orders to shoot all natives you come across but circumstances may occur for which I cannot provide definite instructions.” (Foelsche to Montagu 19.7.1875, in Austin 1992: 15)

16 Letter of 14 July 1875 and addendum of fifteenth, John Lewis papers, SRSA PRG 247, in Reid 1990:67.

17 NTT 4.12.1875

18 NTT 26.1.1878, 2.2.1878; SRSA GRS 1/1/1878/94; Austin 1992: 16.

19 SRSA PRG 247/2, part letter Foelsche to Lewis undated, in Reid 1990: 70.

20 So pleased was the government resident Edward Price with the Aboriginal tracker (from the Oodnadatta district of SA) who guided Stretton's party that he rewarded him with "a double-barrel-fowling piece, together with powder flask, shot belt and a stock of ammunition” on behalf of the government. (Price telegram to minister 26.1.1878 in SRSA GRS 1/1/1878/228; NTT 23.2.1878) William Stretton resigned from the police force later that year and went on to hold a number of government positions, including Protector of Aborigines.

21 SRSA GRS 1/1/1878/118.

22 Tom Traine took over from older brother Alexander Francis ('Frank'). The brothers, from Rylstone in NSW, treated the local Wambaya people with respect, as Tom explained in his memoirs: "The natives of [the] Barkly Tableland were very fine specimens. Many of the men stood over six feet and measured forty-two inches round the chest. They showed no hostility to the white men, unlike coastal natives, and this friendliness was an incentive for us to devise some plan of treating them fairly. We agreed not to interfere with them and they were encouraged to roam about where they liked, but not to hang about the white man's camp.” Traine acknowledged the many instances of Barkly blacks helping lost travellers and explorers, including Ernest Favenc, who named Brunette Creek after the Aboriginal women who took his party there when it was desperate for water. (Traine c. 1920: 16, 13; the Queenslander 10.5.1879)

23 South Australian Register 11.2.1884; McIver 1935: 195; Durack 1974: 137.

24 Alfred Searcy, a customs officer who lived in Darwin for 14 years from 1882, wrote in his memoirs: "Some years ago I got a letter from a man who was attacked by the niggers in the Gulf country, and received some eleven spear wounds. He recovered. In his letter he said, 'I now shoot at sight; killed to date thirty-seven.'” (Searcy 1909: 174) The letter is not among Searcy's papers in the Mortlock Library, but the writer may have been Harry Coop, owner and manager of Calvert Downs station on the Robinson River, who was speared by the local Garrwa people in January 1894. He was known for his sexual abuse of young women. Coop abandoned Calvert Downs later that year.

25 Bradley 1996: 71.

26 SRSA GRS 10/1886/A8997, 20.3.1886; Northern Standard 29.5.1934, 1.6.1934.

27 South Australian Register 21.4.1886.

28 Northern Standard 16.10.1931, 1.6.1934. Gaunt refers to Constable Curtis as 'Smith', perhaps because he was unable to remember Curtis's name and so used a substitute. However, there is strong evidence that he knew all of the stockmen personally and I have verified that all were employed on McArthur River at this time. There was a Constable Edward Smith at Borroloola two years later but he was not present on this occasion. I have gone to some lengths to confirm the accuracy of other aspects of Gaunt's account.;

29 The old Gudanji name for this creek was Tongalongina, but elderly Aboriginal people today know it only as Malakoff Creek. Malakhov was the scene of a bloody battle during the siege of Sevastopol, in which the attacking armies prevailed. Malakoff is also the name of several places scattered across outback Queensland where Tom Lynott had previously worked. The exact location of Malakoff Creek was pinpointed for me on separate occasions by Whylo McKinnon, an old Yanyuwa man who worked as a stockman on McArthur River Station, and Bruce Ah Won, an even older Yanyuwa/Gudanji man who grew up on the station and worked there all his life. Both of them knew Tommy Campbell.

30 Alawa elders Sandy Mambookyi and Chicken Gonagun (who may also be known as Kaludji) lived on Hodgson Downs for most of their lives. In the 1970s, they were asked by historians Peter and Jay Read whether white men ever shot women, children and piccaninnies. They replied: "Women bin run away, they roundem up, shootem.” But babies, they said, were too young to shoot. Sandy continued: "Gottem stick, knockem in the head or neck. Some kid, piccanin', that small one, like a goanna, hittem longa tree.” Chicken added: "Bash 'em longa stone, chuckem longa stone … You know, too small to shoot 'em, too small.” (Read and Read 1991: 15).

Tex Camfoo was born near the Roper River in about 1922, the son of Jimmy Camfoo, a Chinese saddler, and Florida, a Rembarrnga woman. When he was a little boy, his infant sister was killed by white men in the manner described by Sandy: "They grabbed her by the leg and banged her up against the tree. And my aunty Edna Niluk, she got me and ran away in the hills with me.” (Camfoo and Camfoo 2000: 1)

Speaking about events in his country, Dinny Nyliba McDinny, a Garrwa/Yanyuwa man respected for his knowledge of history, described in 1987 how babies were killed with a stick: "hit him just like goanna … hold him leg two fella, kill him like a goanna.” (Baker 1999: 76) Dinny had scars on his back from a flogging with a stockwhip on Eva Downs Station in 1955.

In 1987, Nora Jalirduma, a Yanyuwa woman, told how the bodies of babies were doused with kerosene before being burnt: "Baby, he been hit him, kerosene burn him. They used to make big fire on top. Enough people now, [pour on] kerosene now, and burn him.” This incident occurred when her mother was young, about 1890. (Baker 1999: 76) I have read reports of stockmen carrying kerosene in their saddlebags for this purpose.

31 In 1977, Blue Bob Jayinbadurgi, a Garrwa man, described what happened when his grandfather and grandfather's brother saw a white man for the first time at Manguwarruna, on Seven Emus Creek, near the coast. One brother ran away; the older one was ridden down and shot. The younger brother watched, unseen. The white stockman, Blue Bob said, "found another mob and shot them”. But he didn't burn the bodies straight away - "just leave them - stack them up and leave them”. Then he went across to the Robinson River, about 12 kilometres to the north-west, "shot another few there”, before going back to the camp where the brothers and other people had been living.

The camp was empty except for a baby who was crying. Nearby were the hot coals of a ground oven. Blue Bob described how the white man "put the little kid in there alive, crying, and dug the hole in while he's crying”. Continuing to search, the man "saw another mob of little fellas running about and grab them by the leg, grab them by the leg and hit the tree with it and throw them in the waters and put some in the fire, on the Robinson. This the early days. People been get shot, lot of people.” After pausing, Blue Bob observed: "there would have been a crowd of people today still alive - few here now.” (Borroloola land claim, Exhibit 79: 107, 108, September 1977) Further details are in Roberts 2005: 199-200.

I interviewed Blue Bob a number of times and was impressed by how precisely his accounts, and those of his Garrwa wife, Clara, matched the archival records of events from the 1930s that I was familiar with, yet their information was far more comprehensive. No matter how hard I pushed them for details that might indicate a weakness in their memory or the unreliability of their oral sources, their answers were immediate and impressive. Clara was the daughter of a famous man named Masterton Charley Bajalika / Maddagaranji.

32 Shooting Aboriginals for sport - or fun - was common throughout the Gulf Country. In 1908, the Roper River Mission was established at Roper Bar as a refuge for Aboriginal people, because many were still being shot in that locality (see Roberts 2005: 150-166). Reginald Joynt, later an Anglican priest, was one of the founders of the mission, remaining there for 20 years. In 1918 he wrote: "In years gone by the natives have been shot down like game, and hundreds killed in a spirit of revenge. I have met men that boast of shooting the poor unprotected black 'just for fun'.” (Joynt 1918: 7) Searcy agreed: "There can be no doubt that at times many of the blacks have been put away by some brutes just for the fun of killing, by others for revenge … In many of these cases no report ever reached the police.” (Searcy 1909: 173, 174)

33 Whylo McKinnon, grandson of 'Vanderlin Jack' Rakuwurlma, personal communication, 2009. This story was also told to Richard Baker in the 1980s by Tim Rakuwurlma, second son of Vanderlin Jack. The spelling I use in the essay is not quite correct: I am told that the second part of the name is pronounced with a 't', so the spelling should perhaps be Mundatharrumba.

People were also shot for sport at Yulbarra, on the west coast of the island, and at Murruba, on the southern tip. (For details of these and the reprisals by Vanderlin Jack see Roberts 2005: 190-194.)

34 For people being lined up and shot, or cornered in a cave and shot, see the story by 'Pharaoh' Lhawulhawu, in Kirton 1963-65 (no page numbers). A translation by Dr John Bradley is at Roberts 2005: 198. European sources give other examples, such as the massacre in a cave in the Limmen Bight district (Argus 24.11.1911).

35 Northern Standard 5.6.1934; McIver 1935: 192-199.

36 A table detailing known massacres is at Roberts 2005: 140. Many more have been uncovered since the book's publication.

37 NTT 31.12.1902; Bauer 1964: 157; Cole 1979: 80, 81.

38 NTT 4.10.1884 and letter from Dr Robert Morice in NTT 11.7.1885. Following the murders of the copper miners on 3 September 1884, there were numerous press reports that indicated the government in Adelaide had acceded to the demands of the public - supported by the government resident J Langdon Parsons - that private punitive parties be authorised. Parsons dispatched a steam launch with arms and ammunition for the Southport party on 28 September, after receiving Baker's approval.

39 NTT 4.10.1884

40 This clause had regal and vice-regal origins. Queen Victoria assented in June 1850 to rules and regulations for the granting of pastoral leases in South Australia. They included a proviso that the leases "shall be subject to such conditions as the … Governor shall consider necessary to insert for the protection of the Aborigines”. Lieutenant-Governor Sir Henry Young, mindful of the Queen's instructions and aware of the practical problems faced by Aboriginal people as a consequence of being excluded from pastoral lands (with no right to travel across leased land to reach country unoccupied by whites), took a personal interest in the drafting of the legislation and leases. He ordered the clause below to be inserted into all pastoral leases from 1 July 1851, amid considerable publicity and fierce opposition by pastoralists.

Sir John Downer would have known the history of this issue, as his elder brother and law-firm partner, George, was a northern pastoralist. The clause, as it appeared in the lease for Calvert Downs and other Gulf stations, was as follows:

RESERVING NEVERTHELESS AND EXCEPTING out of the said demise … for and on account of the present Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Province and their descendants, during the continuance of this demise, full and free right of ingress, egress and regress into, upon and over the said Waste Lands of the Crown hereby demised and every part thereof, and in and to the springs and surface water thereon, and to make and erect such wurlies and other dwellings as the said Aboriginal Natives have been heretofore accustomed to make and erect, and to take and use for food birds and animals ferae naturae in such manner as they would have been entitled to do if this demise had not been made …

41 SRSA GRS 1/1/1881/326, quoted in Reid 1990: 89, 90.

42 Quarterly Report on Northern Territory to 31.12.1884, SAPP 1885 no. 53. In 1905, Governor Sir George Le Hunte was sharply critical of successive South Australian governments for their neglect of Aboriginals in the Northern Territory. Three years later, he warned that extinction of the Aboriginal race there was "slowly but certainly approaching” (both statements in Northern Territory, a memorandum dated July 1909, CPP 1909 vol. 2: 1913). By 1907, the Times - under new management - was concerned about general neglect and disease: "The whole Native question is crying out for immediate attention and drastic action … The South Australian Government has been told often enough what is going on … But the extinction of a primitive nation by disease and vice is considered a trifling matter by South Australians.”

43 These massacres were widely known about in Darwin and Adelaide, had been sanctioned by the previous government of Sir John Colton, and were mentioned in the Melbourne press as early as November 1884: "The murders at the Daly River by the blacks have in a sort of way been avenged, but strict reticence is observed as to what was really done by either the police or volunteer parties who went out after the blacks … It is expected that the tribes will take to heart the lesson they have had for this outrage and keep quiet in future.” (Argus 25.11.1884: 9, report from a Darwin correspondent dated 1 November.)

August Lucanus, a goldfields publican, former soldier in the German army and former Territory police constable, led the main civilian punitive party of enormous size. The men were provisioned at government expense, but refused to allow any police to accompany them - a condition accepted by minister Richard Baker. In his memoirs, Lucanus wrote, "The whole country was in an uproar and meetings were held advocating that the niggers should be punished. A party was formed and I was put in charge. We were well equipped with pack and riding horses, also with plenty of food. We went straight to the scene of the murder, and from there followed the tracks.”

Lucanus split his men into three groups: "After a few days we came up with them and there was a scatter. A second party of blacks had split from the party we had followed and dispersed.” (By which he meant the party they had followed and slaughtered.) "They were making for the goldfields and we followed them. After a few days we caught them up and they were dispersed the same as the first mob.” (Clement and Bridge 1991: 16) Such was the size of this party, the infamy of its deeds and its contempt for 'bush blacks' that everyone along the telegraph line from Pine Creek to Darwin would have known the outcome, including the government resident, J Langdon Parsons.

Massacres continued to occur because governments continued to support them. On 31 October 1885, Lucanus was one of the civilians in a police party that massacred Aboriginals in a dawn attack north of the Roper River near Chambers Creek (Roberts 2005: 145-147). This occurred five months after Dr Morice's explosive letter about the Daly River massacres. Clearly, the Downer government had not issued fresh instructions to Inspector Foelsche, nor, apparently, was it bothered by the fact that Aboriginal people were continuing to be slaughtered in the Northern Territory.

44 South Australian Register 2.6.1885, 4.6.1885, reprinted in the NTT 11.7.1885.

45 NTT 23.1.1886. The North Australian, Darwin's short-lived second newspaper, remarked on 8 January 1886: "as to the shooting of blacks, we uphold it defiantly.” On 20 February 1886 the Times stated: "if a hundred of the offending tribe had bitten the dust for each one of the poor fellows who were so brutally attacked, we at least would consider that no more than simple justice had been done.”

46 Educated at Scotch College, Melbourne, Vaiben Solomon became a member of the South Australian parliament and was known for his strong anti-Chinese views. He attended the federal conventions, helped draft the Australian constitution and was a member of the House of Representatives from 1901-03.

47 South Australian Register 8.12.1885.

48 Most, if not all, members of the board of inquiry had connections with the government or with each other. The South Australian Register reported on 26 December 1885 (as did the Adelaide Observer) that the inquiry would be held in secret. While this was true for Adelaide, a notice appeared in the Government Gazette in Darwin on the same day, inviting the public to come forward with information, though the hearings themselves were still to be held in secret (NTT 26.12.1885). Inquiries were conducted in Adelaide by a supplementary board, comprising the minister for the Territory, Sir John Cockburn, and Rev. FW Cox. They interviewed - behind closed doors - Corporal Montagu, then living in Adelaide, but not the two most crucial and outspoken witnesses: Dr Morice, the colonial surgeon and Protector of Aborigines for the Territory at the time of the massacres, who was sacked for criticising those responsible, and Constable James Foster Smith, both of whom were also then living in South Australia.

Smith had taken part in one of the early police patrols, but refused to join the main party under Montagu when they went to the Adelaide, Mary and McKinlay Rivers - the sites of the main police massacres. Smith was later dismissed, but was still in the Darwin barracks when the party returned and was told what had happened. He was so disgusted that he revealed what he knew to the Register (28.11.1885), describing how, on one occasion, the troopers trapped a number of men in a lagoon and "commenced carefully firing upon the natives who were all killed but one”.

When Smith told them they were guilty of murder, they said they were simply following Montagu's orders. However, some were clearly troubled by what they had done, because a number resigned after the massacres and another sought a transfer to South Australia.

Smith also told the Register that Constable Allan MacDonald "was regarded as about the worst shot, and he cut fourteen notches on the butt of his carbine”.

49 In its report of 14 January 1886, the board of inquiry dismissed the notches on Smith's carbine, saying, "his object in placing the marks was totally different from that attributed by the public [i.e. Smith].” (NTT 23.1.1886) Corporal Montagu remained in the South Australian police force until 1902, when he resigned and moved to Victoria, where he worked as an auctioneer. He died in Fitzroy two years later, aged 61; his obituary stated, "As a policeman and a gentleman, Mr Montagu won high esteem from all who knew him.”

50 Nettelbeck and Foster 2007: 115-123.

51 Ibid., pp. 128-130.

52 Willshire became as infamous for his slaughter of Aboriginal people in the Victoria River District as he had been for his behaviour in Central Australia. It is astounding that Sir John Downer would send him back to the Territory under the control of Inspector Foelsche (of all people), to an area far from the public gaze, where cattle-killing was rife and where station managers known for their uncompromising attitudes would welcome his ruthless methods.

Jack Watson, for example, was the manager of Victoria River Downs. He once punished an Aboriginal man, possibly for stealing, by impaling both his hands on a tall sapling that had been sharpened to a point at the top. In 1883, he had 40 pairs of Aboriginals' ears nailed round the walls of his hut on Lawn Hill Station in the Queensland Gulf Country. Watson was a member of a prominent Melbourne racing family and was educated at Melbourne Grammar.

53 SRSA GRS 1/1/1895/211, 8.5.1895 in Nettelbeck and Foster 2007: 152.

54 I have tried to make a conservative estimate of the death toll from frontier violence by district - Central Australia, the Gulf Country, the Victoria River District, the mining and pastoral country from Katherine to Darwin, and Arnhem Land. I used the figure of 600-800 for the Gulf as a basic guide, and also took the size and probable population of the other districts, as well as the extent of known shootings there, into account. While I cannot suggest an upper figure, I am quite satisfied that the minimum could not be less than 3000.

Further, if one were to employ the conservative figure of 600 for the Gulf death toll (for an area comprising 17% of the NT), then that extrapolates to 3530 for the NT as a whole. This was not the method I used, but it does serve as a positive indicator.

55 These prosecutions were for single, isolated cases of murder: I have been unable to find any prosecutions in connection with the widespread frontier massacres that occurred throughout South Australia.

56 Government Resident's Report on Northern Territory for the Year 1887, SAPP 1888 no. 53.