Kakadu National Park preparing for 40th Anniversary

"We work together so hard, we always stick together to come to every meeting and we talk about everything — like our country, our Mirrar children, we don't want them to wander off somewhere else — we want to keep them here, and help us work in our country, to look after our mother country," says Annie Njalmirama, TO.

At the heart of it all, traditional owners are calling for fundamental changes to the lives, opportunities and living conditions of Indigenous people in Kakadu - and that this time, the spoils of tourism will be shared equally.

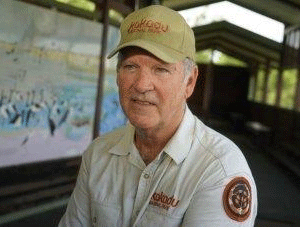

Rangers like Richie Cooper are working hard to preserve country

(ABC News: Steph Zillman)

Stephen Zillman ABC 31 March 2019

In the 1980s, Kakadu was newly inducted into the world heritage listed fold and represented the gold standard in environmental land management.

It was also the only national park in the world to have a joint-management arrangement between the government and traditional owners.

But now on the cusp of Kakadu National Park's 40th anniversary, this land of iconic Australiana is far from postcard perfect.

Pressures like the cane toad invasion, other feral animals like water buffalo and pigs, noxious weeds and poor fire management have meant the nearly 20,000 square kilometre national park is not the pristine land it once was.

There's been an extraordinary collapse in Kakadu's native animal numbers — for example, the brush-tailed rabbit rat is thought to now be extinct from the area, having not been sighted in Kakadu since 2008.

Jabiru Lake will become a tourist attraction under the future plans.

(ABC News: Stephanie Zillman)

Then there's the abysmal living conditions of local Aboriginal people, many of whom were promised the world when the Ranger Uranium Mine was greenlighted in the 1970s.

Riding high on the success of the Crocodile Dundee blockbuster, Kakadu was attracting 250,000 tourists a year in its late 1980s heyday — and that's now dropped back to around 185,000.

Poor tourism infrastructure, persistent road closures around the major attractions, and seasonal weather have all played a part here.

But now for the first time in decades, there are now reasons for local custodians and tourism operators to hope for more.

Earlier this year, the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader each committed $200 million in funds to secure the national park's future — racing each other to Kakadu to make the announcement.

Parks Australia is the government department behind the scenes, whose staff make important decisions from 4,000 kilometres away in Canberra.

Their man on the ground is Russell Gueho, the new park manager, who is tasked with co-ordinating the effort to turn things around.

"The environmental values of this park and how we actually maintain that is always going to be a challenge," he explains.

Russell Gueho, Kakadu's new park manager

(ABC News: Ian Refearn)

But with unprecedented federal money on the way, a plan can now be put in place to change all that.

"It's important that we plan then we make sure we use the resources that we get the best way, and that can also enable us to engage more greatly with traditional owners so they can get back out on country and help with the process of managing the park — and that's where we want to head to.

"Some of the infrastructure is not too bad, it's just that it's been allowed to deteriorate a little bit.

"But as we go through the joint discussion process with traditional owners and other stakeholders on the park we'll be able to identify what needs prioritizing and what needs what and what will give the best bang for buck."

On the Mamukala wetlands in Kakadu's South Alligator region, rangers are working hard towards the park's goals.

Richie Cooper is one local ranger who concedes the work is tough, but says he's living his dreams.

"I always wanted to be a ranger ever since I was a kid, I grew up my whole life in Kakadu National Park and my mum's a TO [traditional owner] for this area," he says.

In 2008, road closures meant Jim Jim falls, and Twin Falls were open for a total of just eight weeks.

It's a sore point for some of the tourist site operators, who say infrastructure like unsealed and low-lying roads are a persistent and major problem.

"We need to keep our vehicles up to a standard as well for safety, and the condition of the road was slowing our vehicles down a lot," says Ben Brown, the general manager of Cooinda Lodge.

He is one of a chorus of operators who also feel Parks Australia has not been doing their bit to advertise the park, and market it to the new generation of visitors.

"We need to tell people that Kakadu is open, because at the moment the general feel is that Kakadu is not open," he says.

Smack bang in the middle of Kakadu is the time warp town of Jabiru — a place founded as a mining town for the Ranger Uranium mine, and somewhere that's incidentally also the gateway to the park.

Under the original contract, the company behind Ranger was meant to remove Jabiru when the mine closed, effectively erasing it from history.

But the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, which represents some of the regions Aboriginal groups, stepped in to ensure Jabiru not only lives on, but is at the centre of Kakadu's tourism revival.

For local traditional owners, the bipartisan funding commitment is a once in a lifetime opportunity.

Kakadu Bakery closed in 2016, and has been empty ever since.

(ABC News: Stephanie Zillman)

"They think yeah this is a great opportunity, it will better change our outstations, our lifestyles, everything will be changed," traditional owner Corben Mudjandi explains.

"And yes, they do feel hopeful, I feel hopeful."

It's also being seen as a way to keep young people in jobs locally, so that they stay on country.

"We work together so hard, we always stick together to come to every meeting and we talk about everything — like our country, our Mirrar children, we don't want them to wander off somewhere else — we want to keep them here, and help us work in our country, to look after our mother country," says Annie Njalmirama, TO.

At the heart of it all, traditional owners are calling for fundamental changes to the lives, opportunities and living conditions of Indigenous people in Kakadu - and that this time, the spoils of tourism will be shared equally.