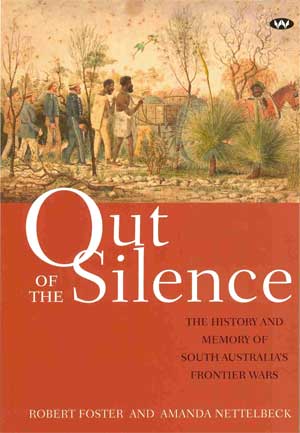

Out of the Silence

Out of the Silence

by Robert Foster and Amanda Nettelbeck,

with extensive footnotes, index and photographs,

is available at $34.95, from

Wakefield Press

Telephone 08 8362 8800

Out of the Silence

The History and Memory of South Australia's Frontier Wars

By Robert Foster and Amanda Nettelbeck

A Review by Nic Klaassen 'Flinders Ranges Research'

As early as 1835 Britain's House of Commons established a Select Committee to inquire into the conditions of Aboriginal people in British settlements. Its subsequent report condemned past policies which had not only sacrificed many thousands of lives, but continued to have disastrous consequences for Aboriginal people. It also admitted the disastrous consequences of European settlement and conduct in Australia.

They had taken their territory, their property, debased their character and introduced vices and diseases. The report further stated that Aboriginal people had a 'plain and sacred right' to their soil but failed to acknowledge the sovereignty of Aboriginal people of Australia.

Regardless of all the nice talks, policies and promises in England during the 1830s, South Australia was invaded in 1836. The British government called it settled instead and pursued a new approach to the treatment of Aboriginal people that would hopefully avoid the horrific violence that had been part of earlier Australian settlement. From now on any acts of violence or injustice towards Aborigines would be punished 'with exemplary severity'.

In their effort to do 'the right thing' the British government declared that as British subjects, Aboriginal people would be seen as equal to the colonists, be safeguarded by British laws and be entitled to the privileges of British subjects. When driven from their land and sacred sites, their food supplies and water it is only natural that the Aborigines would fight back, and they did.

Governor Hindmarsh hoped that the colonists would assist him to fulfil His Majesty's intentions towards the Aborigines by promoting their advancement in civilization and ultimately their conversion to the Christian faith. Naturally it did not turn out as expected. How could it?

Year by year as the frontiers of settlement spread into the interior, dispossessed Aborigines responded to settlers' aggression with aggression. After the largest massacre of Europeans by Aborigines in Australia, in July 1840 when 16 passengers and 10 crew members of the Maria were murdered, it did not take long for any good intension to evaporate.

Other massacres occurred at the Rufus River in August 1841 when at least 30 Aborigines were killed by Overlanders bringing in cattle from the eastern colonies. Little notice was taken from Edward John Eyre when he opined that 'Our being in their country at all is altogether an act of intrusion and aggression'. Aborigines robbed and killed those who first had robbed and killed them.

Worst still was the frontier war at Port Lincoln where Aborigines were shot at random each time whites were killed. Many agreed with summary justice being the best prevention as 'White man's law - a little cold lead, well applied, affected a perfectly amicable understanding between the races'.

The remoteness of new pastoral districts and the difficulty of providing adequate police resources to them seemed almost inevitably to produce a hidden culture of settler reprisals against Aboriginal people. Many went unreported, the only records being hidden in private diaries. In an effort to hide the killings, Aboriginal bodies were often burnt.

If Aboriginal people were arrested and taken to court they had to walk, often chained by the neck, according to Police Commissioner Major Peter Egerton Warburton's detailed instructions. Aboriginal witnesses too were often chained. Warburton, appointed in 1853, posted his Mounted Troopers to protect the settlers, thereby providing some kind of private security force.

When a police station was opened at Melrose it remained the most northerly police station until 1856. Violence in the Flinders Ranges proved to be as bad as that on Eyre Peninsula and the South East. Regardless of the Mounted Troopers there were many killings on both sides of the frontier. An eye for an eye was a common method applied by both parties as taking prisoners was often very inconvenient.

Out of the Silence gives many examples of atrocities committed by Aborigines and Europeans. Aboriginal men women and children were often indiscriminately poisoned, shot, or driven off cliffs as at Elliston. Aboriginal women came in for a different kind of treatment. Europeans were mainly speared or clubbed to death. One shepherd though was killed in 1852, his body ritually mutilated, his genitals cut off and stuffed into his mouth, suggestive of a payback for a sexual crime on an Aboriginal woman.

When the Northern Territory became part of South Australia frontier violence became even worse. For a long time it was out of sight – out of mind. Even though South Australians had for nearly 40 years tried different processes to reduce frontier violence there were precious few successes. They had, and were still issuing rations and blankets to deserving Aborigines, established missions and reserves, on land not needed by settlers, and established a Native Police Force.

Foster and Nettelbeck consider the ways in which these processes unfolded across the evolving frontier and examine how governments and settlers dealt in policy and practice, during the first decades, with Aboriginal resistance to incursions on their land.

Within 50 years of South Australia's settlement settlers were writing their frontier experiences for the benefit of future generations. Some were factual while others were pure fiction. Few of these histories mentioned that they had invaded the country and disposed and murdered the original Aboriginal owners.

With the passing of years settlers were seen as pioneers and Aborigines as a doomed and dying race. It was not just Daisy Bates who believed this. Anthropologist Frank Gillen described the Aboriginal race in 1899 as 'interesting barbarians who began to decay many years before white man set foot in Australia.

By the turn of the century the settlement story and the frontier violence had been told and retold. Aborigines were often portrayed as treacherous bloodthirsty savages instead of freedom fighters. Even today very few people would acknowledge that Aborigines had the right to defend their country and way of life. South Australian centennial celebrations in 1936 had little worthwhile to say about Aborigines in the foundational story.

National, State or local history books, with a few exceptions, published during the 1930s-1950s did not mention any of the frontier violence either. It was not until the Bicentenary of 1988 that Aboriginal history came into the mainstream of history. Foster and Nettelbeck have made a first rate and timely contribution with this publication.

Out of the Silence is a comprehensive examination of the nature and extent of violence between Aboriginal people and colonists on the South Australian and Northern Territory frontiers. It explores the proposition that the 'rule of law' provided the Aborigines with protection from violence, which it did not. It also delves into what really happened on the frontier and how it has been remembered and entered into our understanding of South Australian settlement.

Review by Nic Klaassen