First Nations war heroes 'vanished' from the Anzac legend

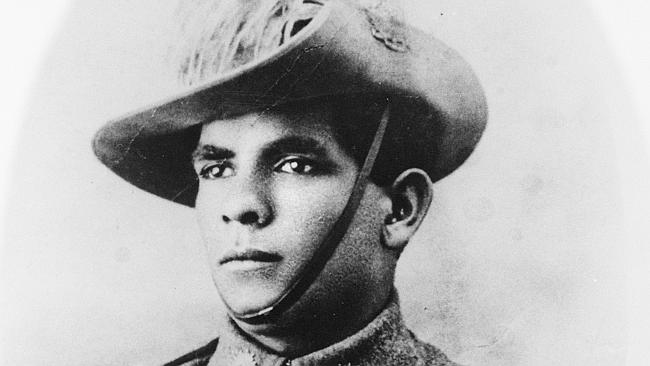

Trooper Horace Thomas Dalton who served in 11th Light Horse Regiment in WWI.

(Daily Telegraph)

Rebecca Franks Daily Telegraph 21 April 2014

Horace Dalton was so keen to fight for his country in 1918, he lied about his "substantial European" origins in order to enlist.

The 19-year-old Queenslander signed up in May, and by August was disembarking in Suez, Egypt, to begin training for the Australian Light Horse Remount Unit.

The young indigenous trooper would fight in the 11th Light Horse Regiment in Egypt for the next year before he was hospitalised with an ear infection and discharged.

It was a short service, but one he gave proudly for the rights and freedoms of his fellow Australians. Sadly, when he returned home in 1919 he found he had few of his own.

Like so many indigenous diggers, Trooper Dalton's homecoming was marred by racism and inequality. It would be 56 years after his death that his contribution would be honoured in a military service in Ipswich.

Strong efforts have been made in recent years to right the wrongs of the past and write our black diggers back into Australia's military history.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were present in almost every Australian campaign during WWI and their contribution was even greater during WWII but they received little or no recognition on their return and in the decades to follow.

Australian servicemen 1915-1916.

(Australian War Memorial)

Some came back to find their children had been taken away or their homes on mission stations were carved up for soldier settlements and distributed to white war veterans - only three Aboriginal servicemen who served in World War I received a land grant.

They were not even allowed into their local RSL to buy a beer and many were prevented from marching on Anzac Day.

"It's like we vanished," Gary Oakley, indigenous liaison officer for the Australian War Memorial, said.

"Many (soldiers) came back from war, took the uniform off, hung it up in the wardrobe and went back to work. Most indigenous people came back to no job."

(News Limited)

He has the names of 1300 indigenous World War I soldiers including 40 who were at Gallipoli - despite being banned from military service before 1917.

Many were knocked back for being Aboriginal and "unfit to serve" so they lied about their background, saying they were Italian, Spanish, South African or Maori.

Mr Oakley believes many more indigenous diggers served and he is still collecting names as their descendants come forward.

(Picture: Jamie Williams - Source: Daily Telegraph)

He said this was difficult as many indigenous people still did not trust government authorities, as a result of years of harsh policies targeting - their communities.

"We're like the Jews, we don't like people making lists," Mr Oakley, a Vietnam War veteran, said. "If you're on a list, they come and take your kids and give you a hard time.

"It's only been the past two or three years that indigenous Australians are not scared of the government anymore, they're not scared to stand up and talk.

"We want to be able to say to our children:"We served too, against the odds'."

(Daily Telegraph)

Dr David Williams, a researcher for the play Black Diggers which premiered at the Sydney Festival, said indigenous people knocked back from military service often travelled to different towns where the rules were not as rigidly enforced.

"People would share information about that process too - if you did not get in at Bourke, then go to Goulburn," he said.

"There are lots of records of medical officers examining Aboriginal people and rejecting them on the basis that they were"too dark', too strongly Aboriginal in their features or too"full blooded'."

(Picture: Lyndon Mechielsen - News Limited)

Mr Oakley, who is calling for a monument to honour indigenous people in the military at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, said it is believed World War I Diggers signed up for an adventure, to earn a good wage of "six bob a day" while some "were one generation from tribal had a sense of:"I have to prove who I am'."

"In the defence force, no one sees your colour, they still don't," he said. "It was the first equal opportunity employer of indigenous Australians.

"Many had the view: 'When we come back to Australia, people will look at us differently because we have defended our country'."

But sadly the opposite was true.

This photograph of WWI Digger, Trooper Horace Thomas Dalton, is kept in the Australian War Memorial's archives. (Daily Telegraph)

|

WWII soldier Eddie Albert, grandfather of artist Tony Albert, served in the Middle East and was a POW in Germany and Italy. (Daily Telegraph)

|

"After World War I and in particular as World War II rolled in, there was a widespread sense from white Australians that they did not want to know that indigenous soldiers served," Dr Williams said.

"It was 100 years ago, all the soldiers who these stories are about have passed on and in most cases their children have passed on.

"Quite a lot were killed (in battle), a lot were held in POW camps. They were suffering the same hardship and undergoing the same experiences as white soldiers.

"It would have been a very difficult homecoming.

"You've been treated the same as everyone around you but now you're not wearing a uniform, you're just another black face and the black face is ‘the enemy of authority'."

(Daily Telegraph)

He said after both world wars, government policies became a lot worse for Aboriginal people.

"World War I and World War II broke a lot of people," Dr Williams said.

"There were a lot of people – indigenous and non-indigenous – who returned from the war very seriously damaged and society did not know how to deal with them.

"It's like we've erased these people from history and not acknowledged the uniqueness of their suffering.

"They went across the world and fought a war that wasn't theirs and there is something extraordinary about that."

(Picture: Phillip Rogers - News Limited)

Next year, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, indigenous artist Tony Albert's sculpture Yininmadyemi – Thou didst let fall will be built in Hyde Park. It will comprise 7m tall bullets, some standing and some fallen to represent indigenous soldiers.

Pastor Ray Minniecon, co-founder of the Coloured Digger Project in Redfern, said it was just the "first step" in recognising the wartime sacrifices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

"This is just one particular piece of artwork or monument to represent the struggle that we have been going through," he said. "We need more."

Mr Minniecon, whose grandfather Private James Lingwoodock served with the Lighthorse Regiment in World War I, said he also wanted a roll of honour listing all the indigenous soldiers and the name of their tribes.

(Picture: Phillip Rogers Souce: News Limited)