First Nations artists fear George Brandis will scrap resale royalties scheme

The visual arts resale royalties scheme was set up mainly to help remote Indigenous artists, many of whom see their work rise in value after they sold it.

The Coalition has long been sceptical about the resale royalty scheme which, even years after it was introduced, has still failed to provide economic benefits to artists as much as it has cost the commonwealth,

Michael Safi The Guardian 11 April 2014

Visual artists fear that the federal government is preparing to scrap a royalties scheme that sees them paid a small commission whenever their work is resold.

Under the resale royalty scheme, which commenced in June 2010, artists are paid a 5% commission each time their artwork is sold, after its initial purchase, for more than $1,000. The scheme is designed to mirror the royalties received by other artists, including composers and writers, when their work is reprinted or used in radio, television or film.

It was hoped the scheme would particularly assist remote Indigenous artists, many of whom sell their work for small amounts, only to see its market value greatly increase in the years that follow.

One Indigenous artist, Johnny Warangkula, died poor in February 2001, seven months after his artwork, Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, sold at Sotheby's for $486,500. Warangkula reportedly sold it in 1973 for $150.

According to statistics from the Copyright Agency, the organisation which collects and distributes the royalties, more than 50% of the total funds generated by the scheme have gone to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists, of a total $2.28m in commissions paid out so far. The value of the vast majority of royalties has been between $51 and $500.

Similar schemes exist in the UK and most of Europe, with China, Canada and the United States considering their own versions.

A review of the system began last year under Labor and will soon be delivered to the arts minister, George Brandis, who will decide whether the scheme should kept, reformed or scrapped.

"This is a right that has been fought over by the visual arts sector for over 20 years," Tamara Winikoff, executive director of the National Association for the Visual Arts, said. "It delivers artists money. And of course artists sorely need income."

But the royalties system is about more than supplementing an artist's income, she says. "It's a matter of principle that establishes the ongoing interest of artists in their work."

By keeping a record of large sales, the scheme also brings transparency to the industry, which Winikoff says is dogged by "some quite shonky practices".

"The commercial side of the industry is regarded as one of the most unregulated industries in the world. It brings a bit more accountability, and in doing that, it's the view of most of us that that strengthens and makes the operations of the art industry more conventional and legitimate," she said.

Whatever the merits of the scheme, the timing has been unfortunate. Australia is generally considered to have survived the global financial crisis relatively unscathed, but the visual arts industry was hit hard, and is yet to recover.

Sales of Aboriginal art alone were as high as $28.5m in 2007, but they plummeted after the credit crunch to $10.1m in 2010 and have continue to fall since.

An Aboriginal art dealer, Adrian Newstead, has felt the brunt of the industry's downturn, and wants Brandis to scrap resale royalties. He says the scheme is an example of good intentions gone wrong.

"It's supposed to kick in after a person has bought an artwork and put it up on their wall and enjoyed it, and then they sell it, and that's when they pay the resale royalty," he said.

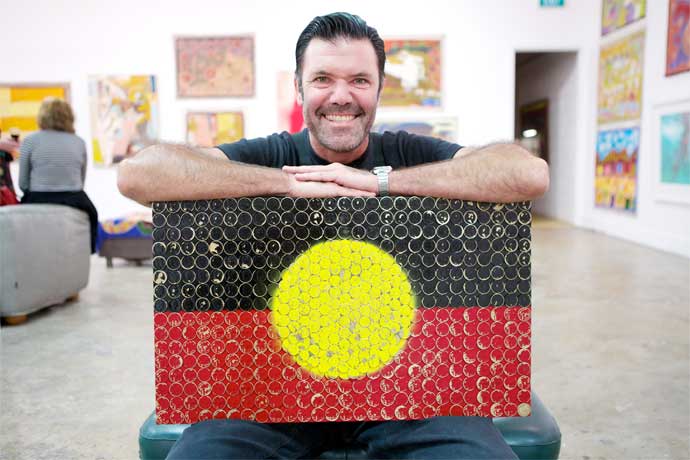

Blak Douglas with his work Trouble or Nothing, 2014

In reality, he says, an artwork changes hands several times before it's sold to a retail customer. An artist might sell their work to an art centre, which sells it on to a gallery, and then on to a wholesaler, and then an international gallery, with a 5% commission paid each time.

"There are three, four, or even five resale royalties payable before the end user actually gets the painting," he said.

"We are already tied up in red tape as it is. Seven out of 10 galleries have closed since the global financial crisis. And none of the galleries that are operating at the moment are making money, I can assure you."

Newstead also says the royalties scheme - "this nightmare," he calls it - does little to help Indigenous artists. "It's yet another passive form of welfare in Aboriginal communities," he said.

He claims that auction houses and galleries could be convinced to voluntarily hand over a small amount from each sale of an Aboriginal artwork to a fund such as the Aboriginal Benefits Foundation, which could distribute the money to health and education projects in Indigenous communities, "instead of $50 or $100 going to an artist who uses it to buy a tank of petrol, or a pack of cigarettes".

For all the passions it has roused, the scheme remains in its infancy. Because it only applies to art acquired after June 2010, the percentage of sales to which the royalties attach will only grow in coming years.

If it makes it that far. Brandis, on whose decision the future of the scheme rests, would not comment, but has previously said he is not a fan.

"The Coalition has long been sceptical about the resale royalty scheme which, even years after it was introduced, has still failed to provide economic benefits to artists as much as it has cost the commonwealth," he told the ABC before last year's federal election.

An exhibition opened this week in Sydney in support of the scheme, and will run until 27 April.