Brown verse Western Australia - Native Title not extinguished

The High Court unanimously held that the mineral leases nor any rights conferred by the Government to the resource companies, nor the arising of the town, extinguished Native Title.

...In my book it will never happen that I will recognise extinguishment as either lawful or proper in any way. But even legally this decision shows that SWALSC has either not been telling us the truth or that they do not know what they are talking about ...

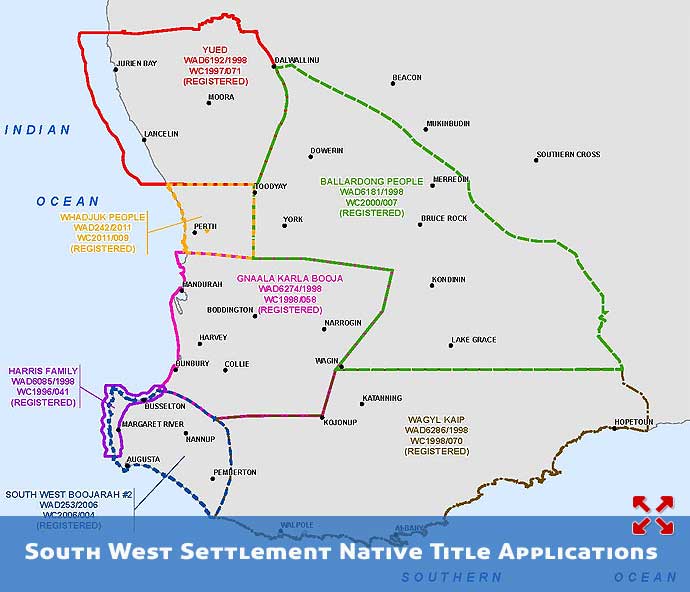

Enlarge/Expand/Legend

South West Settlement Native Title Applications

Gerry Georgatos The Stringer 31 March 2014

(Image: The Stringer)

High profile and well known Noongars - Elders, community leaders and academics - are questioning the validity and the intentions of the Western Australian Government's $1.3 billion Native Title offer after the High Court of Australia unanimously held that the grant of a mineral lease in the 1960s does not extinguish Native Title rights and interests. This is in conflict with previous statements by the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (SWALSC) who argued in negotiating the proposal that many land titles were extinguished, particularly before the mid-1970s.

In the Brown verse Western Australia High Court decision, the decision was important in terms of clarifying the operation of common law extinguishment.

Senior Noongar Elder, Richard Wilkes said the decision undermines the credibility of the SWALSC's right to negotiate the Native Title offer.

"Firstly, the SWALSC do not have the authority to negotiate on behalf of all our peoples. They were created to assist us in our representations and in matters before the Courts, they were not created to negotiate deals with Governments. It is us, the senior Elders and representatives from all our clans who should be negotiating."

"This decision by the High Court only goes to prove that we have never been told the truth by SWALSC who have said to us that Native Title litigation is a gamble and years in the Courts, but so that much of our title claims have long been extinguished. In my book it will never happen that I will recognise extinguishment as either lawful or proper in any way. But even legally this decision shows that SWALSC has either not been telling us the truth or that they do not know what they are talking about," said Mr Wilkes.

"The High Court decision should now put paid to the Government's two-bit terms in their offer to my people and also put paid to the SWALSC as the negotiators."

Noongar rights advocate and 3rd year law student, Marianne Mackay said the central issue in the Brown case was whether Native Title had been extinguished by the granting of mineral leases, or by developments and construction. "This has implications for all tenements but also for the presumption by complacent white dominated society that just because you've built a city on our land we are not entitled to our natural rights."

"What has been upheld is that squatters rights do not mean one has ceded sovereignty, this is something that SWALSC needed to focus on and work with," said Ms Mackay.

Noongar Traditional Owner and Professor of Indigenous Studies at the University of Western Australia, Len Collard, said that SWALSC "has been getting it wrong all along the way."

"There are more than 40,000 Noongars and the majority are not represented by SWALSC, and there are many clans. Extinguishment is an idea of the State, and it needs to be tested till won."

"The State Government's offer is a deal negotiated between the State Government and the SWALSC, not between the State Government and the Noongar people, it returns us very little of what we are actually entitled to," said Professor Collard.

"The deal is worth very little on a per head basis of population."

In 1964, the State of Western Australia signed an agreement to a resources company to develop iron ore deposits in the resource-rich Pilbara, the heartland of Australia's mining boom. However did the State Government have a legal authority to act as if there had been an extinguishment of the custodians of the lands, who had been dispossessed?

The State granted two mineral leases to a joint venture miners, with a requirement that the mining magnates construct a town for the mine site. In time to come the Ngarla People were granted various non-exclusive Native Title rights over the land but there remained the legal question of whether these rights extended to the land that had been seconded by mineral leases. The issue before the High Court was not whether the Ngarla People could exercise traditional rights, including camping and hunting on the seconded land but whether their full suite of rights to the use and ownership of the land had been extinguished by the minerals leases.

The High Court unanimously held that the mineral leases nor any rights conferred by the Government to the resource companies, nor the arising of the town, extinguished Native Title.

"The set of rights belonging to the Ngarla People overrode the set of rights supposed by the State Government. This is a huge step in the Courts for all our people wherever in this nation, but a huge wakeup call to the SWALSC to drop its line that it is not right to argue for land rights here and there because they have been extinguished. Well, the High Court has a different view, and we old timers, we Elders, have never sold out on our view that we have never ceded away any of our land," said Mr Wilkes.

Ultimately, what the High Court found was the Ngarla People's rights and interests were unaffected by grants once various agreed activities on the use of the land ceased. The fact that a town was built and subsequent developments took place does not extinguish Native Title rights and interests.

Lawyers, James Whittaker and Timothy Bunker of Corrs Chambers Westgarth concluded in a joint article, "The High Court's decision has implications for pastoral, mining and other specific purpose leases granted prior 1975 that do not confer a right of exclusive possession. Governments and lease holders should review such leases and consider whether they contain an express or implied right of exclusive possession, and recognise that improvements or other developments on lease sites will not necessarily extinguish Native Title."

But Mr Whittaker and Mr Bunker said that the likelihood "that the decision will impact future Native Title compensation determinations is remote." Despite Native Title rights, the Native Title Act still remains a contrived debacle, designed to some extent to favour State and Territory Governments and resources companies and to cheat the historical custodians. Mr Whittaker and Mr Bunker explained that compensation determinations were limited "because compensation is only payable for extinguishing acts that occurred after 1975, being the commencement of the Racial Discrimination Act."

Ms Mackay said there will come the day that the "1975 line will be challenged in the Courts."

"What future Courts will deliberate is that the 1975 line is notional but premised on the idea that discrimination is not retrospective but by acknowledging that the Racial Discrimination Act forbids further extinguishment as discriminatory then it recognises that discrimination was self-evident prior to 1975 and therefore we will see the day a High Court will finally unfold the justice that we have never let go of in our hearts and minds, but which the State Government would like us to complicate by signing their Native Title offer - this is why it is important not to sign it. The 1964 decision did not extinguish the Ngarla's rights , we are chipping away - and SWALSC must understand we must stay in the right direction, not move away in any way.

![]() Short Particulars - Source: http://www.hcourt.gov.au/cases/case_p49-2013

Short Particulars - Source: http://www.hcourt.gov.au/cases/case_p49-2013

Court appealed from: Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia [2012] FCAFC 154 & [2013] FCAFC 18

Date of judgment: 5 November 2012 & 22 February 2013

Date special leave granted: 12 September 2013

In 1960, a joint venture was established to develop the iron ore deposits at Mount Goldsworthy in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. In February 1962, the West Australian Government awarded the successful tender to the joint venturers. The State of Western Australia and the joint venturers executed an agreement, the operative form of which was given effect to by the Iron Ore (Mount Goldsworthy) Agreement Act 1964 (WA) (“the 1964 Act”). The current joint venturers are BHP Billiton Minerals Pty Ltd, Itochu Minerals & Energy of Australia Pty Ltd and Mitsui Iron Ore Corporation Pty Ltd (the second respondent).

In late May 2007, Bennett J made a consent determination under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) as to the native title rights and interests of the Ngarla People in relation to land in the Pilbara region. Excised from the determination was an area of land which was subject to the Mount Goldsworthy mineral leases. The leases were granted pursuant to a joint venture agreement made in mid October 1964. They were approved and given effect to by s 4(1) of the 1964 Act. An order was made by Bennett J on 5 October 2007 to determine as a separate question whether the Mount Goldsworthy mineral leases were subject to the native title rights and interests of the Ngarla People or whether the rights granted to the joint venturers extinguished those native title rights and interests.

At first instance, Bennett J found that the Mount Goldsworthy mineral leases did not confer exclusive possession on the joint venturers so as to extinguish wholly the native title rights and interests of the Ngarla People, but found that the rights granted under those mineral leases and the underlying agreement were inconsistent with the native title rights and interests continuing to exist in the area where the mines, town sites and associated infrastructure were constructed, but not in the undeveloped areas. As a consequence of this inconsistency, her Honour held that the Ngarla People’s native title rights and interests were wholly extinguished in the developed areas of the mineral

leases.

Brown (on behalf of the Ngarla People), the first respondent, appealed. The appellant and the second respondent cross-appealed, arguing that the trial judge should have found that the Ngarla People’s native title rights and interests were wholly extinguished across the whole of the area which was subject to the mineral leases.

The Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, per Greenwood and Barker JJ, Mansfield J dissenting, allowed the appeal and dismissed the cross-appeal. Greenwood J found that the native title rights of the Ngarla people were not extinguished by the grant but the exercise of the granted rights by the mining companies would prevent the exercise of each of the native title rights (over the whole land) for so long as the mining companies carried on the activities contemplated by the agreement. His Honour concluded that the Ngarla people were prevented from exercising their native title rights over the whole land while the joint adventurers continued to hold their rights as granted.

The grounds of appeal include:

- The Full Court erred in law in finding that the determined native title rights continue to exist in the area of the Mt Goldsworthy Leases when the Full Court should have found that each determined native title right was extinguished in respect of the entirety of the lands the subject of the Mt Goldsworthy Leases by reason both:

- (a) that the grant of the Mt Goldsworthy Leases conferred on the Lessees a right of exclusive possession; and

- (b) that the rights granted to the Lessees pursuant to the Mt Goldsworthy Leases, the 1964 Act and the Mining Act 1904 (WA) were exercisable on all parts of the leased land and were wholly inconsistent with each determined native title right.

The Attorney-General for the State of South Australia and the Australian Lawyers for Human Rights are seeking leave to intervene as *amicus curiae.

All case documents:

High Court of Australia

Case P49/2013 - State of Western Australia v. Brown and Ors