Just 20 years ago suicide rates were at the same rate for all people on this continent

As I travelled to Darwin I received a message on my phone. A father’s son had taken his life and the parents were frightened that another of their boys was going to follow. Just recently another Aboriginal family I know and love had a young girl go to her bedroom, close the door quietly, scribble a final note to the world that had ignored her and then hang herself on the back of that bedroom door.

Jeff McMullen The Stringer 19 October 2013

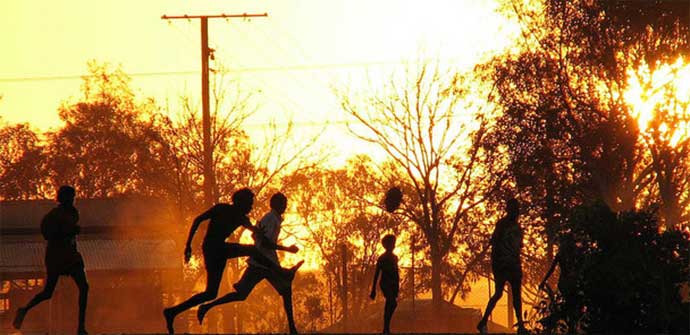

Look at the future through the eyes of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child in any family, urban, rural or in a remote community. These are the Children of the Sunrise, descendants of the world’s oldest and most resilient cultures. Yet can anyone say that Australia has succeeded in offering all of these children today a fair and equal chance of health, a good home, a first-rate education, life-fulfilling work and happiness?

After you have answered truthfully, NO, you must surely wonder are Australians and our Governments indifferent or insensitive, or just plain incompetent and unaccountable? The well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children is the single most important test of whether or not Australia becomes a great society. It challenges those cherished national ideals, the way we view ourselves as egalitarian, fair minded and fundamentally equal.

We have so far failed this well-being test as a nation. Yet even now in the 21st Century we cling to the misguided Government approaches of the 18th, 19th and 20th Centuries. The work of Canada’s Dr Fraser Mustard; the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development under Professors Steven Cornell and Joe Kalt; the Western Australian Indigenous Health Survey led by Dr Fiona Stanley and Professor Ted Wilkes, and the evaluation of well-being by the Menzies School of Health in the Northern Territory, when combined makes a powerful case for genuine community control of Indigenous health. Control over one’s health destiny remains the single most important factor for Indigenous people.

Yet in Australia, dispossession, disempowerment and disrespect remain the major themes of a Government approach that has taken control of so much Indigenous family life. The results we all know are wretched, measured since Dr Brendan Nelson’s day at the Australian Medical Association in those dismal annual Indigenous health report cards and more recently by the Prime Minister’s annual Close the Gaps reports.

The truth is most of the health gaps are not closing. Here in the Northern Territory the real gap in life expectancy is far higher than most official estimates and Aboriginal health services believe it is still over twenty years short of the rest of the population. Professor Jon Altman of the ANU’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research has warned that it could take a century to close the gap in life expectancy if Australia persists with the same misguided approach.

The burden of Syndrome X, that cluster of chronic illnesses including diabetes, renal illness, strokes, hypertension and heart disease, is cutting the heart out of another generation. There are disturbing indicators to show that many Indigenous Australians feel trapped in a downward spiral of physical and mental illness.

Even just 20 years ago Indigenous suicide rates were at the same rate for all Australians. Today, Indigenous youth suicide and self-harm are in crisis proportions in some but not all communities. We need to look urgently and thoughtfully at this pattern to understand why in some places there is hope and in others almost total despair. In the Northern Territory, for example, the percentage of all age Indigenous suicide has increased from 5% of total suicides in 1991 to 50% of the total in 2010. The most alarming increase, however, is among young Indigenous people aged 10 to 24. Indigenous youth suicide in the NT increased from 10% of the total in 1991 to 80% of the total in 2010.

Aboriginal parents who call me when they have to bury a son or a daughter are beyond consolation. As I travelled to Darwin I received a message on my phone. A father’s son had taken his life and the parents were frightened that another of their boys was going to follow. Just recently another Aboriginal family I know and love had a young girl go to her bedroom, close the door quietly, scribble a final note to the world that had ignored her and then hang herself on the back of that bedroom door.

Aboriginal people know that here in the Northern Territory and in Queensland Governments have not only ignored the cries for help but have slashed funding that could provide experienced doctors and counselling services through community based programmes that have demonstrated great success in preventing youth suicide. Yarrabah, near Cairns for example, has had an extraordinary degree of success in preventing the pattern of youth suicide once so menacing in this large community.

The Government’s statistics underplay the suicides of the youngest children. They are usually counted as “accidents”. Nonetheless the Australian Human Rights Commission reports a 160% increase in Indigenous youth suicide through the six years of the most oppressive and discriminatory policies of the Northern Territory Intervention. This link between disempowerment and despair is obvious.

Criminalising alcohol offences instead of treating alcoholism as a disease, forcing people into rehabilitation and punishing parents whose children do not attend school, is counterproductive social engineering, built on a misguided belief in assimilation. Ignoring the very real social damage caused by its policies, the Government is consumed by internecine bickering over Ministerial and bureaucratic failure while children suffer. Alarmingly, the response from the Chief Minister, Adam Giles, here in the Northern Territory, has been to support the removal of Aboriginal children from their families. Of the 40,000 Australian children now in out-of-home care, over 13,000 of them are Indigenous children. Although all governments are supposed to have signed onto important priority principles to see that such children are put into the care of Aboriginal extended families, this isn’t happening. In the Northern Territory, 66% of children removed are left with non-Indigenous families. The community services system around this country is overwhelmed because our approach to the wellbeing of children, families and whole communities is deeply flawed.

In my lifetime I have watched Aboriginal families moved from humpies to larger tin sheds and still overcrowded houses, from 44 gallon drums for water to leaky toilets and sewage running across children’s playing areas. I see rusted cars pulled up around tumbled down walls, plastic sheets flapping in the rain and children sleeping on mattresses in overcrowded rooms.

I would like to hear just one Prime Minister or Chief Minister have the guts to admit that we would all be sick and sorry if we were forced to endure such poverty. Bob Hawke shed tears, Paul Keating laid out the pattern of pain in his Redfern speech and Kevin Rudd apologised, but our political leaders have never carried their political parties, let alone the nation, to end this poverty in our own backyard.

If there is to be a new, healthier tomorrow for Indigenous Australians we must end the controlling, disempowering approach, invest in the social determinants at a community level and shift our trust to Aboriginal people to manage their own destiny.

Dr Jeff McMullen AM - The 42nd William Conolly Oration. Royal College of General Practioners. Darwin. October 15th 2013