Makarrata v Treaties

Some may argue that Australia is an independent Nation, but we can never forget that Australia's sovereignty is that of the English Crown and they govern accordingly.

What adds to the complication and uncertainty is when HRH Elizabeth II leaves the throne Australia will make its move to become a Republic and a new constitution will have to be written, or a referendum will be held to retain the one that we now have!

So if we are to go forward and agree to negotiate Treaties, then we must also ask who are we Treatying with, if at all? Are there other alternatives?

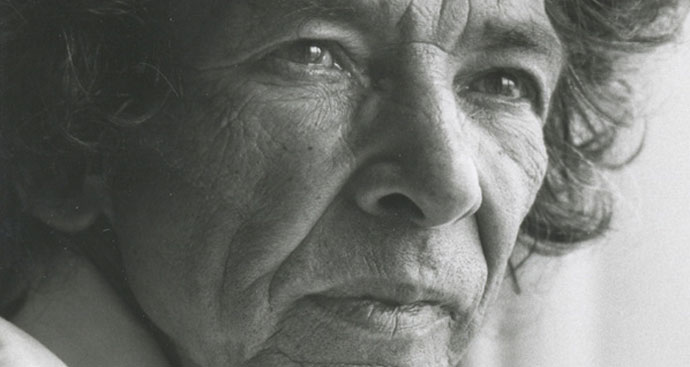

Kevin Gilbert, Wiradjuri 1933 - 1993. Activist | Photographer | Poet | Printmaker | Writer | Artist

A Statement from the Bush

Ghillar, Michael Anderson 18 August 2017

To treaty, or not to treaty? This is the question.

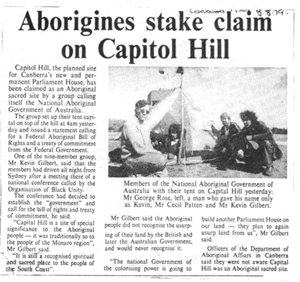

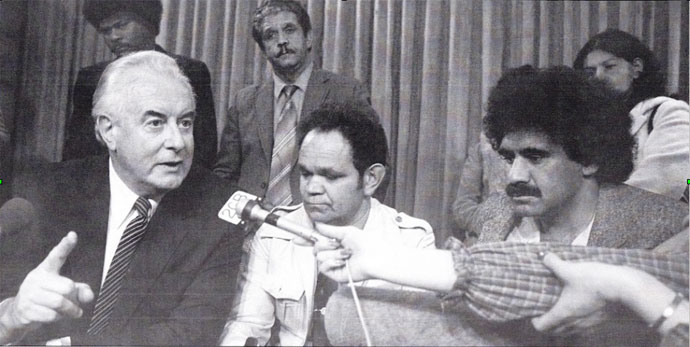

1979 witnessed a bold protest movement on top of Capital Hill, Canberra, before the new Parliament House was built. It is important to identify the key players in this protest. It was led by Kevin Gilbert (1933-1993), along with the late George Rose, the late Cecil Patten and Kevin Wyman.

Kevin Gilbert told the reporters at the time that Aboriginal people did not recognise the usurping of their land by the British and later the Australian Government, and would never recognise it. He is quoted as saying:

In his book Aboriginal Sovereignty, Justice the Law and Land (pdf), Kevin Gilbert described how the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC) had already called for a Treaty of Commitment and the protest camp on Capital Hill, which started on 7 August 1979, highlighted the assertion of 'Sovereignty Never Ceded'. He wrote:

Accordingly resolved that we immediately convey our moral, legal and traditional rights to the Australian Government and that we immediately proceed to carry from our people the suggested areas to which the Treaty should be relevant and that we proceed also to draft a Treaty and copies of the Motion be sent to the Prime Minister and to all Members of the Australian Parliament.

(National Aboriginal Conference Sub-Committee on the Makarrata brochure, July 1980)

"Knowing that our previous applications to have our proper status in land, our rights to compensation and our sovereignty recognized had, to the mid 1970s, availed us little, either in white society or the legal avenues of redress in white Australia, we called a National conference to be held in Redfern in August 1979, where the National Aboriginal Government representatives were chosen and sent to erect a camp on Capital Hill, Canberra, on the proposed site of white Australia's new Parliament House."

![]() Expand & Enlarge Image

Expand & Enlarge Image

National Aboriginal Government, Capital Hill, Canberra

![]() Expand & Enlarge Image

Expand & Enlarge Image

National Aboriginal Government, Capital Hill, Canberra

The camp on Capital Hill was called the National Aboriginal Government (NAG) and the representatives were demanding that their sovereignty be recognised through a Sovereign Treaty and that the Commonwealth Parliament also introduces a Bill of Rights, for which Kevin Gilbert had written a draft. The call was for a Sovereign Treaty under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which means that the Sovereign Treaty is constitutional, is governed under international law and overrides internal laws.

Ten days later on 17 August 1979, on behalf of the group, Kevin Gilbert wrote to the then Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. He identified the key issues of Aboriginal Nations' continuing sovereignty that had never been ceded, the need for a Sovereign Treaty as a way forward, along with a Bill of Rights.

PM Fraser delivered his reply on 21 August. It was addressed to Kevin Gilbert, Capital Hill, Canberra. PM Fraser concluded that he and his government were prepared to consider a Treaty with the then elected body the National Aboriginal Conference:

The National Aboriginal Conference vigorously pursued the Treaty concept and the Fraser-led coalition government agreed to pursue negotiations for a Treaty of Settlement.

It is important to understand that the original three person Sub-Committee of the NAC who pursued the Treaty were Cedric Jacobs, a Jadjuk Ngoonar, Lois O'Donaghue and Lyall Munro Senior. The NAC was quick to put out a brochure of key issues, that had come to their mind at the time, to stimulate discussion.

The government provided funds for the NAC to have community-based discussions for the development of a national framework of issues that had arisen in the community consultations.

The NAC chose not to have regional or State-wide meetings, because on such a sensitive issue such as negotiating a Treaty for all our people, it was vital to hear the peoples' voices from within their own communities. The NAC ensured that they avoided elitism, where a selected few who have the total say and/or direct the thinking on ways forward.

Interestingly enough, the NAC brochure that was being circulated at the time included the issues of Land Rights, compensation, self-governance, return of skeletal remains and artefacts from the world's museums, return of cultural icons to name a few.

In 1981 I was engaged by the NAC as the Director of the Treaty process, at first in secondment from the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) in NSW. I later resigned from the DPP and took up a full-time position with the NAC as Director of the Treaty process. Having taken up the position full-time, I immediately recommended to the NAC Executive that they needed to engage specialist consultants in constitutional international law, politics, economics and property law to assist the NAC to go forward fully informed.

In 1984 the NAC had reached a satisfactory position in respect of identifying 27 key aspects that were continually emerging in community consultations across this country.

On the other side of the Treaty process we had to obtain sound constitutional and international legal advice in respect to the true definition and legal standing, both domestic and international, of a Treaty. The thoughts at the time that had been prevailing within the NAC were how do we make this Treaty secure and strong and thereby avoid the negativity and falsehoods that exist in the Treaty of Waitangi and the treaties of Turtle Island, that is, USA and Canada.

One of the questions that hung over our heads at the time was: Will our Treaty be governed by international law under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties and overseen by UN treaty bodies, or do we acquiesce to the Australian government and negotiate a domestic Treaty governed by Australian law, in right of the Crown of Britain. The latter meant that we had to acquiesce and cede our pre-existing and continuing sovereignty.

These were matters that had not yet been concluded by the NAC executive and further research was being conducted at that time.

On the issue of security and the power of the Treaty, we looked at both the domestic and international processes. The legal position was that the Australian Constitution, as it exists, has constitutional heads of power that permitted the Australian government to negotiate a Treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

There were two primary factors involved, that is, can the Australian government negotiate a Treaty under international law and governed by international legal principles? And do they have the capacity to negotiate a domestic Treaty which has constitutional backing?

The answer to both questions was 'yes'.

The NAC's legal advice was to first determine whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were in fact citizens of the Commonwealth. If not, then the Treaty could only be negotiated with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples as 'aliens' and foreigners to the Australian legal system. This question raised a whole new arena of thought, because John Howard's position as Treasurer and some of his colleagues on the Executive Government were of the opinion that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were citizens of the Commonwealth and, if this were true, then their position was: We cannot negotiate a Treaty with our own citizens.

This statement on citizenship is still being bandied around, e.g. by Tony Abbott. I believe this was the whole reason for the recent Referendum proposal to include First Nations Peoples in the constitution, thereby coercing our people to consent to be governed as citizens and so settling the legal question of citizenship, once and for all. As we know now our grassroots people were awake to the trickery and any thought of First Nations negotiating a Treaty/Treaties must first have this question legally settled.

The National Aboriginal Conference was fully aware of the position the Federal Government had chosen for itself. The Federal Government was constantly arguing over what we considered were semantics. This was best illustrated in the Government's written response by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Peter Baume, to the Makarrata/Treaty Sub-committee declaring on 3 March 1981:

In fact, in the same document on the issue of nationhood of Aboriginal Peoples, Minister Baume expressed concern that if the government were not diligent and serious enough about the Treaty negotiations, they were facing a potential disaster. He wrote:

He went on to cite a United States court case The Cherokee Nation v The State of Georgia (1831). Using this case, Minister Baume continued:

At the end of this quote the Minister cited in brackets an example when he referred to the United States (sic) Charter, Article 1, and the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. In concluding this point Minister Baume said in clause 8:

On the question of constitutional powers to negotiate a Treaty it was agreed that in any type of Treaty, be it under international law or domestic law, the Australian constitution could be used to give the Treaty constitutional backing and standing.

Section 51(26) was the only Section in the Australian Constitution that permitted the Australian government the power to negotiate anything with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples, There is no other section in the Australian Constitution that permits the Commonwealth government of Australia to pass any laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples.

The NAC examined the issue of the rights that we could demand in a Treaty, particularly those under international law in respect of Human Rights at the time. We must be reminded that this was pre the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UNDRIP), but now we can include UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a base that would also underpin any Treaty negotiations in terms of a rights-based agenda that the Commonwealth government can exercise under the External Affairs power Section 51(29). The Commonwealth Government could only use this section if it were to negotiate a rights-based Treaty and if we are to draw upon international human rights based instruments. By the using these existing constitutional means we could achieve a rights-based Sovereign Treaty, using international law as the base of these rights.

The NAC's position back then was that we had to have more community-based consultations because only half the country had been covered in four years. To this end former PM Fraser agreed and made an extra $3million available in 1984 so as to permit the NAC to complete its community consultations for going forward.

In fact, when the NAC executive had its last meeting with the Commonwealth Executive Government it was advised by PM Fraser that the NAC had reached a position where they could now take their negotiations to the colonial State Premiers of Australia, and thereby commence negotiations so as to get the States agreements on the terms that had been developed in the interim as key negotiating points going forward.

Kevin Gilbert highlighted the fact that the Treaty process was being undermined by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs who introduced the now familiar word 'Makarrata' :

It has put aside the idea that caused concern - namely that a treaty between nations was being sought. What is being sought is an agreement about what is needed by and due to the Aboriginal people.

In finding the Aboriginal word 'Makarrata' they have adopted its meaning for this proposed agreement - the end of a dispute and the resumption of normal relations.'

"Thus, a sovereign Treaty would not be entertained, because a TREATY was an agreement between two sovereign powers and Aboriginals were not considered 'equal', were not sovereign. Hence the Blacks were given the choice of nothing or else to enter into a common agreement, called the 'Makarrata', with the Government. The bone to the dog."

After advice had been given to the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) on the NAC's position going forward with the Treaty the Aboriginal people within the DAA had a meeting with the NAC Executive, where they tried to argue that the NAC's position was untenable and unrealistic. Then began a personal campaign of attack against the NAC Chair, Lyall Munro Snr, and myself as Director of Research. This delegation and oppositional arguments were led by the late Charles Perkins. Through Lyall Munro Snr the NAC, however, made it clear in that meeting that the NAC's position was firm and I do recall the late Charles Perkins expressing some concern that Aboriginal people were talking about unrealistic expectations. But in the NAC meeting with the Prime Minister and his Executive Government PM Fraser made no such comment and, in fact, encouraged the NAC to take their points to State Premiers and their governments and to continue the NAC's community consultations across Australia.

What was absolutely alarming from my perspective, however, was the fact that in the meantime a national election was called for at a time when the NAC had changed its position from calling the negotiations a Makarrata and back to the word Treaty. This position was made on the basis of two pieces of advice: Firstly, the Santa Theresa Elders in the NT pointed out very clearly and in no uncertain terms that if the NAC proceeded with the use of the term 'Makarrata' they they did not want anything to do with it, because as ceremonial Elders they knew the true meaning and nature of an action under Makarrata. They implored the NAC to use the whiteman's term 'Treaty' that in their opinion was more suitable. Secondly, after understanding the Commonwealth's fear of the word Treaty, because of its international sovereignty legal implications, the NAC realised the trickery behind using the term Makarrata and changed back to the sovereignty position of Treaty.

The outcome of the national election resulted in the Hawke Labor government being elected and we now know that key Aboriginal opposition to the NAC Treaty was supported, surprisingly enough, by the Labor party and it is not surprising that the funds of the NAC were cut and the NAC Treaty process died at that point.

The NAC had concluded that one Treaty would never fit all and it could only set up a national framework underpinned by the key issues that came out of the community consultations.

Key proponents of the death of the NAC Treaty process can now be named: Les Malezer, Heather Sculthorpe, Pat Dodson, supported by Nugget Coombs, who convinced the Hawke Labor government that he had worked with Pat Dodson and others to found an organisation called the Federation of Aboriginal Land Council's which went on to found Regional Land Councils such as Northern Queensland Land Council and Kimberley Land Council.

After the demise of the NAC Treaty process, Kevin Gilbert continued to talk up the meaning of Sovereignty and Treaty through the Treaty '88 campaign. In 1987 he published Aboriginal Sovereignty, Justice the Law and Land to articulate the Sovereignty Position for First Nations and to stimulate discussion to keep the Treaty process alive and to educate people on what sovereignty really is and its inherent rights. Like the NAC, he insisted any Treaty had to be a Sovereign Treaty as a framework under international law.

As a discussion document, he wrote a 'Draft Treaty', which included the NAC's 27 key points that arose from the NAC's consultations. In the 1987 Draft Treaty he comprehensively articulated many of the inherent sovereign rights belonging to Aboriginal Nations and Peoples. It must be remembered that this Draft Treaty was published 30 years ago and was a tool to educate the people on their sovereign rights by asserting that Aboriginal people in Australia are entitled to treaty.

Former PM Bob Hawke receiving the Barunga Statement, June 1988

Finally, PM Bob Hawke made a statement at Barunga, NT, that he would negotiate a Treaty and signed the Barunga statement, but like most political promises they are not kept. In fact Hawke back peddled the very next day saying he was meaning a 'compact' not a 'Treaty'.

First Nations now assert that they are independent Sovereign Nations, and an increasing number are declaring their independence through the accepted international norm of Unilateral Declarations of Independence (UDIs).

If we were to use the European of model of nationhood then those treaty 'experts' in Australia need to respect the terms of the very first Treaty which was the Treaty of Westphalia. If the legal experts understood the legal history in international law, then they should not fail to ensure that Treaties in Australia, going forward, must be underpinned by the intent and outcome of the Treaty of Westphalia, and secured under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

The cruel irony now is that these Land Councils, while previously working to destroy the NAC Treaty process, now seek leadership on negotiating a Treaty with the Commonwealth of Australia, while trying to ignore all that went before them. But I can say to the government that no matter how hard they try they will have to revisit all that the NAC already achieved, along with the Treaty '88 campaign. Failure to do so will be a complete acquiescence and ultimate cession of all that we hold dear as First Nations Peoples in Australia.

In conclusion, we have not only have to settle the issue of First Nations citizenship but our people must ask themselves: Who are we going to negotiate with when Australia is still a self-governing bunch of colonies, which became federated in 1901 and which now only has the right to be self-governing in right of the Crown of England?

Australia only governs itself by a right granted to them from the British parliament, and their laws are not legal unless the English monarch's agent in the form of the Governor-general and Governors assent to them and sign them into law.

The most strategic move for First Nations, at this time of an imploding Commonwealth government wracked by illegal parliamentarians who hold dual citizenship in breach of the Constitution, is to rise up and rebuild the governance, independence, cultural and economic development of one's own Nation and then for our First Nations to treaty with each other first, just as the Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) have done, demonstrating a way forward. The more First Nations treaty amongst themselves, the more the writing is on the wall for the colonial government ruling in right of the British Crown.

Some may argue that Australia is an independent Nation, but we can never forget that Australia's sovereignty is that of the English Crown and they govern accordingly.

What adds to the complication and uncertainty is when HRH Elizabeth II leaves the throne Australia will make its move to become a Republic and a new constitution will have to be written, or a referendum will be held to retain the one that we now have!

So if we are to go forward and agree to negotiate Treaties, then we must also ask who are we Treatying with, if at all? Are there other alternatives?

Contact: Ghillar Michael Anderson

Contact: Ghillar Michael AndersonConvenor of Sovereign Union of First Nations and Peoples and Head of State of the Euahlayi Peoples Republic -

Contact Details for Ghillar