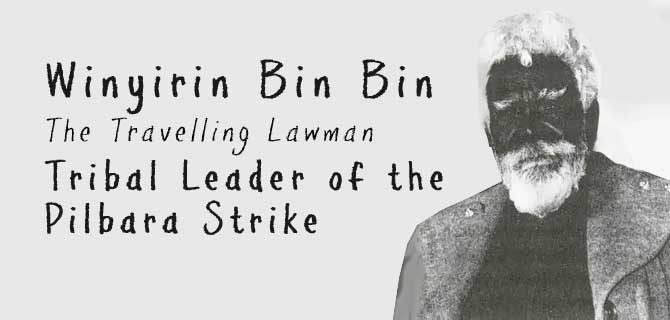

Winyirin (Dooley) Bin Bin the Travelling Lawman who coordinated his countrymen on a pastoral strike from 1942 to 1946

The Strike: At the meeting of tribal leaders Winyirin Bin Bin was nominated, in his absence, to work with a non-Aboriginal social reformer, Don McLeod, as a representative of the inland’s Aborigines. He and his kinsman Clancy McKenna sought a minimum wage of thirty shillings per week for Aboriginal station-hands and planned a mass withdrawal of labour if the request were refused.

Although most of the accolades for leading Pilbara Strike is usually given to Don McLeod, without underestimating his hard work, connections and tireless effort supporting the people in the Western Australia's grazing frontier, it was Winyirin Bin Bin who coordinated the strikers across the vast Pilbara region, an area around three times the size of Victoria.

Although most of the accolades for leading Pilbara Strike is usually given to Don McLeod, without underestimating his hard work, connections and tireless effort supporting the people in the Western Australia's grazing frontier, it was Winyirin Bin Bin who coordinated the strikers across the vast Pilbara region, an area around three times the size of Victoria.Dooley (Winyirin) Bin Bin (c.1900-1982)

In most of the publications regarding the Pilbara Strike, Don McLeod gets the highlighted, and although he did an amazing job supporting the 'workers' in the Western Australia's grazing frontier in the vast Pilbara and the Kimberley (both are around three times the size of Victoria) it was Dooley (Winyirin) Bin Bin, the 'Travelling Law Man' who led the strike and co-ordinated the Aboriginal slaves in the wider regional sheep stations.

Winyirin Bin Bin, Aboriginal community leader, also known as Winyirin, was born about 1900 in that part of the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia traditionally occupied by Aborigines who spoke the Nyangumarta language. His mother was called Martukaninykaniny; his father’s name is not recorded. Bin Bin’s childhood coincided with a period when Western Desert groups from the interior were moving into neighbouring riverine and coastal country.

When he was 9 or 10 he cleared spinifex from the recently constructed rabbit-proof fence, east of what was later known as Barramine station. After his preliminary initiation into manhood in 1911, he moved between stations throughout the de Grey River system and by the 1930s had established a reputation as a `travelling Law-man’ who merited respect.

One of several Nyangumarta who were generally attached to Warrawagine station on the confluence of the Oakover and Nullagine rivers, Bin Bin retained a view of the world and a system of values that were increasingly threatened. His commitment to his people’s law, his capacity to talk straight and his ability to stand up to the white man were discussed at a meeting of Aborigines from the Western Desert region held in 1942 at Skull Springs on the Davis River.

At the meeting he was nominated, in his absence, to work with a non-Aboriginal social reformer, Don McLeod, as a representative of the inland’s Aborigines. He and his kinsman Clancy McKenna sought a minimum wage of thirty shillings per week for Aboriginal station-hands and planned a mass withdrawal of labour if the request were refused.

'How the West Was Lost' - short 'Australian Screen version'

The movement challenged pastoralists in the Pilbara and was to have wider repercussions for politicians, trade unionists and clergymen. To Bin Bin, who was impatient to act, and McKenna fell the tasks of coordinating the protest and of holding the waverers firmly to the cause. On 1 May 1946 workers from some two dozen Pilbara stations walked out. The initial wave of strikes lasted until late 1948.

While the issues of wages and working conditions were important in triggering the boycott, Bin Bin and other strikers such as Daisy Bindi strove to dismantle wider social injustices which had been legally perpetuated by the Aborigines Acts of 1905 and 1936.

The three strike leaders, Bin Bin, McKenna and McLeod, were arrested early in May 1946 (the two Aborigines being sentenced to three months’ hard labour) for `enticing’ Aborigines from their places of employment. They received wide support when human-rights activists lobbied on their behalf. Amendments made to the Native Administration Act in 1954 were probably influenced by these events.

After his early release from gaol in June, Bin Bin was part of a group, led by McLeod and established as Nomads Pty Ltd, which attempted to set up Aboriginal mining and residential co-operatives in the Pilbara. Eventually it acquired Strelley station near Port Hedland; Bin Bin lived there as a senior member of the `Strelley mob’.

Dooley BinBin Tribal Strike Leader, facing camera, in 1961 (Image: John Wilsin)

Bin Bin remained a forceful, stubborn and single-minded advocate of the traditional values of his people, for whom he endeavoured to achieve social justice and economic security.

Photographs reveal a person of strong purpose, and suggest the reserve and dignity that he embodied as a lawman of `high degree’. Survived by his wife and son, he died on 24 December 1982 at Port Hedland and was buried in Strelley cemetery.

From The Black Eureka by Max Brown 1976 p115)

Further reading:

Don McLeod, How the West was Lost, published by the author, Port Hedland, 1984 - VIDEO