You are here

Search by issue

Media Releases & News

- SU Media Releases

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2022

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- General Statements

- Sovereign Treaties: International Law

- Walkout Statement from Sacred Fire

- Proclamation (with video Readings)

- UDI's Explained

- What is 'Decolonisation'?

- Uluru Statement from the heart

- Sovereign Manifesto of Demands

- NO CONSENT to Recognition

- Submission on ILUA Amendment

- Uluru Statement video testimonials

- Uluru Statement grassroots videos

- Complexity of Treaty and Treaties

- Understanding Treaty & Treaties

- Official SU Meetings

Sovereign Union Menu

- Self Governance

- International

- Treaty - Treaties

- Sovereignty

- General Principles of Sovereignty

- First Nations sovereignty defined

- The Sovereignty Debate

- Sovereignty into Governance

- Reform: Practicing sovereignty

- Sovereignty after Mabo

- What about Sovereignty?

- Current sovereignty debate

- Sovereignty protest Qld

- Research papers & Theses

- Sovereignty never ceded -thesis

- SA sovereignty challenged

- Rosalie Kunoth-Monks leads the way

- Pacific Islanders Act 1875

- Asserting Aboriginal Sovereignty

- Aboriginal rights then & now

- Michael Kirby Oration

- Academic Paper : Songlines

- John Howard recognised sovereignty

- Queen Victoria: Crown owns nothing, Aborigines sovereign

- Rejecting 'recognition'

- Yingiya Mark Guyula Speach

- New Way Summits

- Decolonise

- August

- Australia: UN Questionnaire

- July

- Law against Genocide Bill

- Rally: 'Let us go Home'

- Ray Jackson: 30 years of light

Special Features

- History

- During Invasion

- Invasion

- 1788-2014 Invasion to Resistance

- 'The condition of the natives' 1905

- Mapping QLD massacres

- Cooks Instructions & Diary

- Whites & Blacks during the colonisation in the late 19th Century

- Australia's history of slavery

- Dad 'n Dave - The Qld killing fields

- Treatment of Aboriginal Prisoners

- 'Conspiracy of silence' blood baths

- British Parliament Report 1837

- Culture

- Horrors of North West WA

- Ignorance & Racism

- Invasion

- Post Invasion

- Stolen Remains and Collections

- Culture

- Kitty Wallaby: Dreamtime & colanisation

- Improve heritage management

- Unlock secrets of rock art

- Kurlpurlunu found in Central Australia

- Forgotten' Woolwonga tribe for 130 years

- First Nations rock art is at risk

- Language diversity threatened, study

- Languages Treasure trove

- Pressure to lose values and culture

- Languages reveal scientific clues

- Ignorance & Racism

- Father of the Stolen Generation

- Aboriginal counting myth won't go away

- Pleading letters to 'Protector'

- 1926 plan for an Aboriginal state

- First prisoner abuse inquiry 1905

- Legalised slavery: hidden reality

- The second dispossession

- Rottnest Island internment camp

- Meston's 'Wild Australia' Show 1892-1893

- Stolen Wandjina: Cultural Appropriation

- Whitefellas destroyed our bible

- Fraser Island Death Camp

- Intervention to kill self-determination

- Ongoing Warfare

- Pre Invasion

- Culture

- Genesis

- Out of Australia - Not Africa

- confirmation of genetic antiquity

- WA's Mid West History 30K

- 'Australian' peoples were first Americans

- How First Nations saw the Stars

- Ice Age struck First Nations people hard

- Kimberley paintings could be oldest

- Misunderstand First Nations science

- Sea-Level recorded

- James Cook's Secret Instructions - 30 June 1768

- Trading & Hospitality

- Landcare, Science, Agriculture

- Captain Cook

- During Invasion

- The Frontier Wars

- Memorial Marches

- The Frontier Wars

- Anzac Gathering 2012

- Aboriginal servicemen honoured

- 1905 Report WA's North

- Anzac Day Videos

- Battle for FF memorial

- From invasion to resistance

- Frontier Wars Remembered 2016

- Image Galleries

- Invasion & Sovereignty

- Invasion Day Callout for 26 January

- Memorial ignores frontier war

- The Freedom Fighters

- Truth about the Gulf country

- Conflicts/Massacres

- Massacres & Trophies

- Mixed Media

- Canberra 2016

- Closing the Homelands

- Homelands explained

- Central Articles

- Closing Homelands for mining

- Vital for ecosystems

- Terra nullius never went away

- Barnett's plan to axe homelands for years

- Fed Gov't $100 million deal with states

- Mining: $10,000 job sweeteners

- Abbott rejects international law

- Barnett's War on Health

- Anatomy of Racism in 2015

- Food supply autonomy needed

- Freedom Summit: WFD Media Release

- Funding: Confusing-fractured-racist

- It's OK to discriminate

- The demise of Coonana community

- Sovereign Union Articles

- Reports by State & Territory

- Video - Images - Audio

- Rallies

- Media Reports

- Homeland Closures

- 'Recognition' Constitution

- Nuclear Waste Dumps

Key Topics & Issues

- NT Detention Hearings

- NT Intervention

- Sovereign Embassies

- All Embassies - Map

- Embassies

- Canberra Tent Embassy

- Perth Sovereign Embassies

- Portland Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Sovereign Embassy

- Brisbane Embassy - Home

- What is Brisbane Embassy?

- 2013 content

- 2012 content

- New Stolen Generation rally

- Police arrest sovereigns

- Politically motivated eviction

- Brisbane - Eviction notice

- Brisbane Embassy meets CMC

- Brisbane conference 2012

- Charges dropped but ...

- Council meets Elders

- Embassy arrestees protest

- Embassy midnight raid

- Embassy to be shut down

- Fire destroys Embassy

- Musgrave heritage listing

- Sovereigns charges dropped

- Moree Sovereign Embassy

- Broome Tent Embassty

- Woomera Sovereign Embassy

- Airds Sovereign Embassy

- Gugada Sovereign Embassy

- Tent Embassy in Airds, Campbelltown

- Call for Embassy tolerance

- Embassy Articles & Media

- Land, Sea & Water

- Northern Murray Darling Basin

- Water Treaty Talks: Murray-Darling Basin Nations

- Mining Country

- Adnyamathanha people of the rocks

- Ancient approach to global emissions

- Danger: Developing the North

- First Nations Land Management

- Historical sites in NSW

- Clark and Mansell: trading beef

- David Suzuki: Aboriginals best bet

- Dingoes may save wildlife

- Fires support mammals - research

- First Nations had villages and farmed

- Homelands vital for fragile ecosystems

- Hunter gatherers Myth - Bruce Pascoe

- Kangaroos win after hunt with fire

- Race to protect ancient rock art

- Kakadu Park 40th Anniversary

- Land rights and the government

- Native 'wild' rice in Australia

- Native Title amendments slammed

- Ngoongar Grower group using Native Youlks

- WA Aboriginal Heritage Act overview

- Sovereign Neighbours

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- December

- October 2013

- September 2013

- Emergency Protest of Illegal Deportation

- FF activists a test for Abbott government

- West Papuans Deported to Port Moresby

- Six West Papuan's flee after ceremony

- Freedom Flotilla claims success

- Sacred water and fire celebrated

- Ceremony completed in secret

- Military buildup in destination port

- Men released: Treason charges pending

- Julie Bishop incites military action

- Threats to turn back boat

- Four arrested at FF Welcoming

- Time for human rights in Papua

- August 2013

- Media Files

- Articles - Free West Papua Movement

- Atooi Unification Ceremony

- Atooi now has jurisdiction

- Australia & Fiji union

- Canada Day: Time of Mourning

- Canada First Nations alliance

- Canada: Commercial fishing rights

- India: Ruling against mining co

- Indigenous rights struggle

- North American Indians seek Sovereignty

- Statue honors US freedom fighters

- The Creation of one world gov't

- Vanuatu: Pacific custom land tenure

- Arizona tribal law system

- Canada: Tsilhqot'in peoples win ruling

- Embassy meets Indonesians

- Grandmothers: worst ever stealing

- Ibans acquired native customary rights

- Maori did not cede sovereignty

- UN: Canadian Aboriginals in crisis

- West Papua - Freedom Flotilla

- The Invasion

- A day of sadness

- Health and Social Issues

- Suicides & Depression

- Suicides just happened?

- Nothing will be done about the suicides

- First Nations suicide rates

- Gov't not listening - People die

- 77 suicides in SA alone

- 996 deaths by suicide

- Hundreds will suicide if we wait

- Suicides: 'A humanitarian crisis'

- Suicide is humanitarian crisis

- Suicide epidemic worldwide

- Noongar x3 suicide rate

- Falsely arrested & drugged

- Cashless Welfare Card

- Family breakdowns causing repeats

- General Health Issues

- Government Policies

- Youth suicide at crisis point

- Negatively framing policies

- A little boy who hid under the bed

- Defend and Extend Medicare

- Call for help results in children stolen?

- Doctors in communities in WA reduced

- Children and human rights

- Our children more likely to be removed

- Justice? wake up WA

- Need for Bilingual schools

- Racism Effects

- Rosie Fulton

- Work-for-the-Dole Unhealthy

- Youth lost in prisons: Amnesty

- Suicides & Depression

- Gross Abuse

- Genocide and apartheid

- National

- States & Territories

- Suicides

- Imprisonment & Deaths

- International Critisism

- Genocide

- More Gov't Abuses

- Mining and Destruction

- Racism

- Racism Game in Australia

- 27% say it's OK to be racist

- Abbott backs out of Racism changed

- Genocide by Apartheid Australia

- How Bolt should be punished

- Racial discrimination in Australia

- Racism Media

- Racism driver for ill health

- Racism is a health issue

- Racism worse than Sth Africa

- Reform: Just Ask Black Australia

- Unpacking White Privilege

- Welcome to Dja Dja Wurrung Country

- White Australian National Anthem

- Solidarity

Media & Resources

Activism and Politics

- Activism

- Homelands

- For the record: Sovereignty Never Ceded

- Freedom Fighters memorial call

- Anthony Fernando 1864–1949

- Fernando's Ghost - Transcript

- Historic Videos and Images

- Australia’s dirty secret

- Deebing Creek development

- Pilbara pastoral strike

- Pro-Black Isn't Anti-White

- Truth Telling Uluru Statement

- UN slams anti-protest laws

- Whitlam: Legacy of Wave Hill

- Winyirin Bin Bin, Pilbara Strike

- Politics

Royal Commission 'The condition of the natives' Perth WA 1905

More evidence, more recommendations and more mistreatment, dis-empowerment and dispossession. How many Royal Commissions do you need to treat First Nations people with dignity and allow us to be who we are, and be free from all the disasters and gross abuse of decolonisation. The righteous and paternalistic non-Indigenous people on this continent haven't changed one little bit in 227 years.

-

View the full image

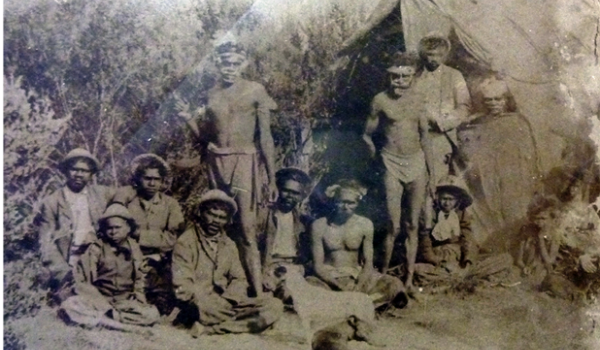

Dispossessed and homeless. Native Camp, Strelley Street, Busselton, in 1901, near Henry Prinsep’s home, Little Holland House, on the Vasse River.

-

View the full image

These people are possibly Karajarri traditional owners, camped in the vicinity of 'LaGrange bay' rations station after being forcibly dispossessed from their tribal lands.

-

View the full image

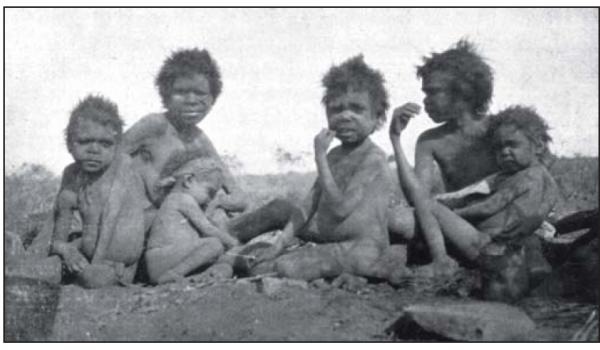

'Natives' at a Pilbara station, Corunna Downs, 1905. Some of the children were fathered by white men, who were often set away to work as domestics or farm labourers in other location.

-

View the full image

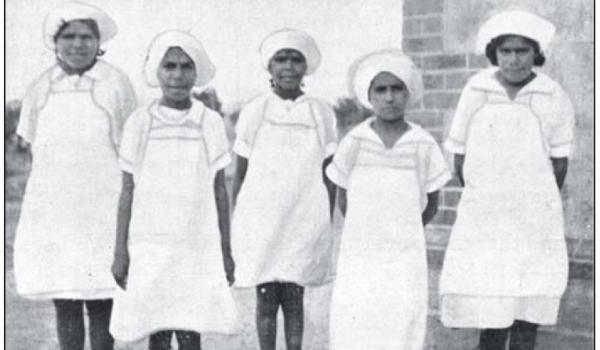

Image 1 of 2: 'Girls living under the stone age system' Source: Gov't Human Rights website

-

View the full image

Image 2 of 2: ‘Native girls living under civilised conditions’ Source: Gov't Human Rights website

-

View the full image

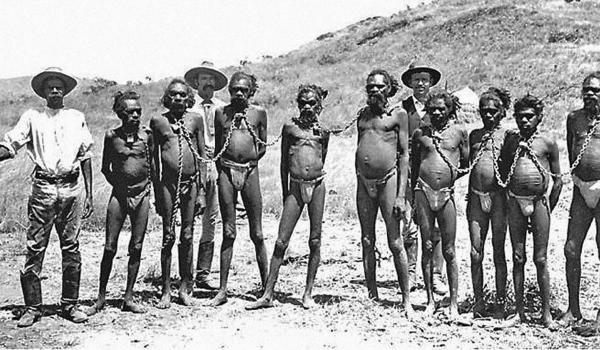

1896: Aboriginal prisoners in chains are photographed outside Roebourne Gaol.

-

View the full image

The ‘half-castes’ of Ellensbrook in 1902, from left to right: Ivy, Miss Griffiths, Tommy, Emil-Penny, Mary, Frank, Dora and Jennie (Jean Jane) Councillor

(1.) THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE ABORIGINES DEPARTMENT.

The Chief Protector of Aborigines has no legal status [207]*, while his authority as head of the Department controlling the welfare and protection of the natives is a divided one [206], and may be even ignored; indeed, so far as the labour conditions of aborigines are concerned, honorary justices are invested with greater powers. With the exception of his Clerk-Accountant he has no subordinate officers from whom, as a matter of right, he can command obedience in the execution of his instructions, though it is true that other Government officers are assisting him, but only as a matter of courtesy [210-13, 843].

There are believed to be only one or two Protectors of Aborigines gazetted: one Resident Magistrate believes and acts as one from an ex officio point of view [1902]. The Chief Protector daily meets with difficulties in regard to not possessing necessary powers for even enforcing the provisions of the present imperfect Acts and, until quite recently, in his efforts to obtain redress for the representations made on behalf of the natives admittedly under his care, has not met with that encouragement which he had a right to expect [216-8].

All the Resident Magistrates examined approve of decentralisation in the working of the Department [324, 898-9, 1629,1921], an approval recommended by the Chief Protector himself [208], in the sense that there should be one person responsible for each district and that one responsible to Head Office. One man cannot thoroughly understand the whole State, the work being much [1629]: what the whole thing really requires is constant, active, report personal supervision, there being so many chances for abuses [1921] It should not be in the power of any justice to interfere [643] with this local, as distinguished from the Chief, Protector. In the opinion of another witness, in the West Kimberley District, honorary justices ought to have nothing whatever to do with aboriginal matters. Sometimes such an individual, on account of his treatment to natives, is not even fit to be a justice, nor is his proposed appointment to such a position necessarily referred to the Resident Magistrate [1975-7].

Your Commissioner recommends legislation on the lines of Sections 3 to 10 of the Aborigines Bill as laid before Parliament this last session: "A Bill for an Act to make provision for the better protection and care of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia."

Amongst the duties of the Chief Protector, additional to those defined in this Bill would be the regular inspection of all aboriginal institutions subsidised by the Government.

The Clerk-Accountant should be relieved of his accountant's work [220-2], which could be transferred to the Treasury, where vouchers would be paid only on the Chief Protector's certificate. As clerk he would thus have more time to devote to his specially departmental duties, and train himself for the position of Acting Chief Protector when that gentleman is away on his annual inspection work.

With regard to the local Protectors, each should act as the assistant and deputy of the Chief Protector, and should report to him, and communicate direct with him in all matters or aboriginal interest: Each should forward to him a monthly return or all convictions, prosecutions, and relief issued in his district as well as an annual report. As these local Protectors will have extra duties and heavy responsibilities, great care should be exercised in their appointment - a matter in which the Chief Protector should necessarily have a say: where possible, use should be made or the Resident Magistrates or senior police officers. Honoraria varying from £50 to £25 per annum should be given for these extra, services.

(2.) THE EMPLOYMENT OF ABORIGINAL NATIVES UNDER CONTRACTS OF SERVICE AND INDENTURES OF APPRENTICESHIP.

Aborigines are employed with or without contracts, and under indentures of apprenticeship.

A. With Contracts (50 Vic., No. 25, Part II). - Intended for service on land only and for

aborigines of 14 years of age and upwards, the particular form of contract and attesting certificate is permissive, even the one at present in force not being strictly in accordance with that laid down in the schedule to the Act. In order to protect the interests of the native as to age, absence of coercion, etc., the attesting certificate has to be signed by a Justice of the Peace, a Protector of Aborigines, or some proper person specially appointed by the Resident Magistrate.

The interests of the native are certainly not protected against the fitness or unfitness of his or her future employer, there being nothing [17] to prevent the greatest scoundrel unhung, European or Asiatic, putting under contract any blacks he pleases. It must be admitted that it is permissible for the Minister (61 Vic., No.5, Sec. 11) to cancel, owing to the employer's unfitness, a contract when once made, but as at the same time there is nothing to prevent working a native without contract, such a prohibition is valueless.

Furthermore, the contract may be entered into without the sanction or knowledge of the Chief [15] or other Protector, and without the opinion of the local chiefs of police being consulted [334, 616, l080] indeed, there are at present employers of aboriginal labour to whom, were it in their power, the police would raise objections [330, 1081]. The Protector, the person most concerned for the native's welfare, has thus no means of satisfying himself whether the contract is a just one or not. One justice may attest a contract which another has refused [828]. Owing to the police not being consulted or advised, difficulties often arise; for instance, if a native deserts a warrant is issued, but until such issue, the patrolling police do not know whether any native they may come across is absconding from his lawful employment or not [342]. The period of service must not exceed 12 months, and the contract has to be signed by the employer or his agent: this latter stipulation is objectionable in that the native does not realise his proper master [7] and may have objections when he discovers what kind of an employer he is bound to.

Besides rations, clothing, and blankets, the employer has to supply medicine and medical attendance where practicable and necessary, unless the illness of the aboriginal be caused by the latter's own improper act or default. One witness [18] points out that venereal disease is not included altogether in the latter category, because the infection may have been imparted to the woman by a white man, and the aboriginal may have contracted it in all innocence; another [l928] is still more emphatic when he states that while the native is under contract this class of disease is considered to be the result of his own fault, which he strongly urges it seldom, if ever, is.

It is permissible for any Justice of the Peace, on hearing of a complaint, to cancel the contract, irrespective of any other decision; order, or judgment in the case: a Protector of Aborigines specially charged with the aboriginal's well-being has no such power. Again, any justice, but not a protector (unless he is himself a J.P.) may cancel a contract certain grounds. The cancellation of a contract can thus be effected without even the knowledge of a protector. Wages are not stipulated for in the contract, and it is only in about one case out of seven that they are alleged to be paid.

A total of 369 contracts (258 men, 111women) is known to the Chief Protector [19], while the number in receipt of wages [22] according to their contract is 53; on the other hand, he has no means of satisfying himself whether the wages are actually being paid [26]. It is compulsory on no one to keep either a register or copies of the contracts, though the clerk accountant of the Aborigines Department keeps a book [221] of natives under contract, based on such particulars as may be forwarded to the office by courtesy.

Breaches of contract are provided for, but the Act (55 Vict., No. 25) brings into prominence an unjust inequality of punishment for the two contracting parties: the native may receive up to three months' imprisonment, with or without hard labour, while the employer can only be mulcted by fine. What might have been expected as the outcome of a system of contract, wherein all the advantage is on the side of the employer, has come to light; the Chief Protector [30-33] knows of no conviction of an employer for breach of contract, but during the past three years has received information of 20 cases against natives. Similar experiences are reported by the Broome[619, 620] and Roebourne [1087-8] police.

Though the magistrate has no power to do so under the Act just cited, the absconding aboriginal is sometimes ordered back to his or her employment. Warrants are issued for native women absconding from service [1089]. In the Roebourne Gaol your Commissioner saw an aboriginal female, "Sally", who had been sentenced by the acting Resident Magistrate on the 29th October, 1904, to two weeks' imprisonment for this offence: the sub-inspector informed him that no previous summons had been served on the defendant, who had been arrested on warrant.

Employers have benefited themselves pecuniarily by hiring the services of their aboriginal employees to others: the Aborigines Department has had to issue a circular pointing out this illegality in the case of aborigines under contract [213]. Apparently, the employer of a native under contract to someone else cannot be punished, although the aboriginal is subject to penalties for absconding.

B. Without contracts.-No action can be taken against an employer for working blacks without contract, the commonest form of service. The proportion of natives under contract (already stated to be 369) to natives actually employed is one in twelve [20], as compared with the census taken three years ago by the police.

Amongst the employers of the 4,000 natives thus estimated in service, there are many to whom the police [330, 970, 1688] would be prepared to object, but at present they are powerless to act. According to the evidence brought before your Commissioner, none of these natives throughout the North-West receive wages. There is a sort of code of honour (sic) amongst the pastoralists [1685, 1880-1] to the effect that one station owner, etc., does not interfere with his neighbour's blacks, the outcome of which is apparently to prevent them absconding. Being anxious to learn, if possible, what action was actually taken in order to bring such runaways back, inquiry was made from a pastoralist who, while denying that he either flogged or whipped them [1879], admitted that he used no force further than the command that he had over them as being their "master" [1878]; yet this same gentleman had only a minute before stated [1876] that his reason for not putting his blacks under contract was that if they would not work of their own free will he always considered they were not worth having.

Even without contracts the blacks are not free to come and go as they please. The assistance or the police is also invoked to bring such runaways back, an official acquiescence which is of course quite illegal: the native is practically forced to work for his so-called master. While under such circumstances the absence of a contract does not prevent the employer securing and enforcing the services or the aboriginal, it relieves him of all responsibilities in the way or rations, clothing, and maintenance during sickness.

C. Indentures of Apprenticeship (50 Vict., No. 25, Part IV).-Acting under instructions from the Aborigines Department, a Resident Magistrate "may bind by indenture any half-caste or aboriginal child having attained a suitable age as an apprentice, until he shall attain the age or 21 years, to any master or mistress willing to receive such child in any suitable trade, business, or employment whatsoever."

That children are being indentured without permission from the department [755, 843] and certainly without its knowledge, is evident from the fact that while the Chief Protector has received information of about 50 cases [48], the commission has obtained evidence of at least 85 [745, 838, 1094]. There is no compulsory notification to head office, and it is apparently no one's business to keep copies or a register or these indentureships; no regulations are in force to protect the interests of the children so bound to service. The form of indenture used Appendix A) is in accordance with the schedule or the Act. On the other hand, the form issued under the Industrial Schools Act (38 Vict., No. 11) is different [38]; the manager of such institution, e.g., Swan Native and Half-caste Mission may issue it independently or instructions from the Aborigines Department.

Indentures of apprenticeship are clearly applicable to children only of tender years; cases of boys [750] and girls [755], 17 and 16 years or age, being indentured are clearly evasions of the provisions or the contract system, which, as already mentioned, is intended to cover the service or aborigines or 14 years and upwards (50 Vict., No. 25, Sec. 19).

With regard to the most suitable age at which a child can be indentured as laid down by law, the Chief Protector considers this to be about six years [36]. It being only permissive for a justice or protector to visit apprenticed children, your Commissioner is not surprised to learn that, with one exception [838], no one knows or its ever being done [51, 746].

No education and no wages are stipulated for in the indenture. The very spirit and principles of the Pearl Shell Fishery Regulation Act or 1873, which absolutely forbids a term of aboriginal service on the boats longer than twelve months, have been stultified by recourse to the system of apprenticeship: at Broome quite one-half of the children, ranging from 10 years and upwards [750], are indentured to the pearling industry [747] and taken out on to the boats [748,751]. The Chief Protector draws special attention to the fact that he cannot prevent male children being employed on the boats [62].

One witness approves of the indenture system if under proper supervision, but objects to the clause in the Act referring to the assignment of apprentices on the death of the master [842]: another considers it fairly useful if under proper restrictions [1098]: several express the opinion that the term of service up to 21 years of age is too long, the limits of age suggested varying from 14 to 18 [756, 841, 1139]. Others object to the system altogether. One Resident Magistrate [1909] very ably expresses the present state of affairs as follows :-The child is bound and can be reached by law and punished, but the person to whom the child is bound is apparently responsible to nobody. Even the Chief Protector is obliged to admit the injustice of a system where, taking a concrete case, a child of tender years may be indentured to a mistress as domestic up to 21 years of age, and receives neither education nor payment in return for the services rendered [55].

D. The question of wages.-Witnesses are almost unanimous that services rendered by the native should be paid for, differences of opinion arising only out of the question whether the moneys should be paid direct [339, 618, 1919-20] or into a fund to recoup the Government for the expense of granting aboriginal indigent relief [320, 368, 834, 985-8, 1085-6]. The two notable exceptions to the unanimity [24, 320] express views which have evidently been influenced by possible retaliatory action on the part of the pastoralists, though one of them certainly upholds the principle when he admits it to be a reasonable stipulation [108] to make each contract conditional on one destitute aboriginal being rationed for every native lawfully employed.

It is true that in the more settled districts on nearly all stations the policy is to fence and erect windmills to enable the owners to be independent of black labour [904]; and rumours are certainly current [865] that if too many restrictions are put upon the service of the natives they will be dispensed with. As the law stands, the pastoralists cannot rid themselves of black employees from off their runs (62 Vict., No. 37, Sect. 92, Schedule 24) provided they want to hunt there.

On the other hand, the natives may be offered no encouragement to remain; by depasturing the stock on all the watered portions of the [25]; by destroying the kangaroos; by dropping baits for the aborigines' hunting dogs; by limiting, in the way of fences, the areas throughout which native game can be obtained; by taking proceedings against blacks for setting fire to the grass, etc. At the same time, the evidence tends to show that in many cases the squatters act with humane consideration [24], and that people who have always had natives as servants will not part with them [904]. Should, however, any retaliatory measures be put into practical effect there is nothing to prevent the Executive resuming the whole or portion of the runs so complained of, and proclaiming them reserves for the sole use of the natives [903].

Your Commissioner recommends the legislation covered by Sections 19 to 21, and Sections 24 to 31, in the proposed Aborigines Bill. The sooner the indentures of apprenticeship are cancelled the better. In order to prevent the present abuse of maintaining the native only during a few months at a time and then turning him adrift to shift for himself, when if under contract he is prevented working for anyone else, provision should be made in Section 31 that if his leave of absence is extended beyond the limits mentioned therein the contract will lapse.

If children of school age are in employment and a school is available, the employers should be compelled to fulfil their duties in this respect as the legal guardians under the Education Act. The police should be instructed not to lend any assistance whatever in the way of bringing back runaway natives, except of course when armed with proper warrants. With a view to recouping the Government for the expense not only of granting aboriginal indigent relief, but also of benefiting the natives generally and the half-caste waifs and strays in particular, your Commissioner further recommends a minimum wage of five shillings per month on land and ten shillings per month on boats (Q. 1902, No.1, Sect. 12), exclusive of food, accommodation, and other necessaries; the period of leave of absence to be also paid for.

By Sect. 60 of the proposed Bill, both aborigines and half-castes may, under certain circumstances, be exempted from the provisions of the Act, including the labour conditions.

(3) EMPLOYMENT OF ABORIGINAL NATIVES IN THE PEARL-SHELL FISHERY AND OTHERWISE ON BOATS.

Separate written agreements with indorsement [37 Vict., No. 11, etc.] have to be entered into between natives engaged for employment in the Pearl-shell Fishery, "or any other industry which shall necessitate the conveyance of such aboriginal by sea to the scene of such industry."

The indorsement, which can be signed by an Inspector of Pearl Fisheries, a Resident Magistrate, a Protector of Aborigines, or a Justice of the Peace, is with a view to safeguarding the interests of the native so far as freewill, length of service, etc., is concerned. The person who indorses has to take and keep a copy of the agreement. Aborigines can thus be employed on the boats contrary to the wishes, and even without the knowledge, of the chief or other protector; nor are the particulars of such employment bound to be communicated to him [59, 60].

On the local boats at Broome [757] there are about 25 natives signed on and about 20 whose agreements are not witnessed (indorsed), although there is no doubt that these 45 are working on the boats. These natives are employed at cleaning shell or as boatmen (not as divers), and are sometimes retained to keep a watch on the rest of the crew, so as to prevent pearls being stolen [807-8]; they are all on a twelve months' agreement [759], and receive no wages [760, 730]. The practice at Broome appears to be for Western Australian natives not to be signed on the ship's articles, evidently [720, 723] on the excuse of the special agreement with indorsement, which is not necessarily even properly filled in; the Port Darwin natives here have to sign articles.

Male children, as already mentioned, are taken to sea under articles of apprenticeship, i.e., by evasion of the spirit and intention of the Pearl Fishery Act. Native women are taken on the boats [1312-1317, 1833] in strict defiance of the Act. There are unseaworthy boats engaged in the industry [783-4, 793-8], that one witness thinks it is to the pearlers' interests to keep in use [800], and that carry aborigines [785].

Of the 400 odd pearling boats engaged in the North-West fisheries, the Shipping Master at Port Hedland [961] and acting Sub-Collector (acting as Shipping Master) at Broome [715] do not know which or how many are registered under the Merchant Shipping Act, a rather important item of information considering that, provided the vessel be not registered, she cannot be prevented going to sea if unseaworthy [714, 962]. Furthermore, both these officers are doubtful [7-26, 963] whether they can stop a vessel carrying more men than her articles show. Apparently there is no compulsion for the luggers to carry lifebuoys. Owing to their being no aborigines engaged in deep-sea diving, it hardly came within the scope of the present commission to inquire into any results directly attributable to the extraordinary absence of any compulsory Governmental inspection of the diving gear. Vessels are not boarded by a Shipping Master on his own initiative [966] even if at all [716, 725]. The Act gives any justice, etc., power to board a vessel with a view to examining the stores, there is nothing to show that this has been exercised within recent years; one witnesses' boats have not been boarded and examined since 1886 [801]. There is no limit to the amount of liquor, opium, etc., which a boat may take to sea; of the former, your Commissioner is informed that this is sold to the crew as "goods supplied" for slop-chest purposes at the rate of ten shillings per bottle for whisky and from twelve to fifteen shillings for gin. The administration of the Pearling Acts at Broome, the centre of the pearling trade, is admitted by the acting Resident Magistrate to be very mixed [761].

Along the whole coast-line extending from a few miles South of La Grange Bay to the Eastern shores of King Sound [71], drunkenness and prostitution, the former being the prelude to the latter [66], with consequent loathsome disease [1278-1281], is rife amongst the aborigines. This condition of affairs is mainly due to Asiatic aliens [1217] allowed into the State [738] as pearling-boats' crews by special permission of the Commonwealth Minister for External Affairs and allowed to land from their boats under conditions expressed in I. Ed. VII., No. 17, Section 3, Subsection K. The boats call in at certain creeks, ostensibly for wood and water, and the natives flock to these creeks, the men being perfectly willing to barter their women for gin, tobacco, flour, or rice [675]; the coloured crews to whom they are bartered are mostly Malays, Manillamen, and Japanese [810]; they frequently take the women off to the luggers [70].

Direct evidence of this state of affairs comes from La Grange Bay [127 5-1 292], from Beagle Bay, where your Commissioner saw native women at daybreak returning to shore from the boats with presents of rice, etc., and from Cygnet Bay [1833-4], where the disgraceful state of affairs and effects of disease on the aborigina1 population are more fully detailed [1968]. One magistrate considers that the whites are just as much to blame as the coloured crews for the prostitution going on where the boats land for getting wood and water [769-770].

As the result of their intercourse with aboriginal women, the boats' crews suffer a good deal from venereal disease, and the loss of their labour is severely felt by the pearlers [812-3]. During about three months in the year the fleets lay up at Cunningham Point, Cygnet Bay, Beagle Bay, and Broome, as well as at other places: except perhaps at Broome, this laying-up season is taken advantage of by the more unscrupulous of the pearlers to swell the profits of the slop-chest by getting rid of their supplies of opium and of liquor, no small portion of the latter ultimately finding its way to the natives as payment for prostitution.

A still greater evil, and one which may have disastrous results in the future, is that both the Malays and the natives, with whom they are at present, allowed to consort, possess in common a certain vice peculiar to the Mahometan. It is highly probable that this habit, practically unknown amongst the autochthonous population of other parts of Australia, has been introduced along this North-West coast-line by Malay visitors during past generations; the fact remains that these aliens are being admitted into the Commonwealth.

Further beyond King Sound, along isolated patches of the coast-line, pearling vessels certainly do land, and their crews bring fire-arms ashore [1968]. A witness states that Asiatic crews may camp on shore while the boats are being overhauled, and also during sickness [775]; according to the form of surety now issued by the Sub-Collector of Customs, Form No. 15, they can be engaged in any duties ordinarily connected with the vessels.

With a view to minimising the sexual intercourse between the Asiatics and aborigines at present existing and its resultant evils, the following recommendations have been suggested : Power to be given to the police to order the men back to their boats [675] ; reserves to be proclaimed where boats only should be allowed to land, but no aborigines to enter, and vice versa [74, 814-818, 1304-5, 1311], and the chartering of a patrol boat [68, 1308].

One witness suggests that under proper supervision the male natives could earn their own living by cutting wood and getting water for the boats [1305].

Your Commissioner recommends the passing of Sections 22, 23, 32, 42, and 43 of the proposed Aborigines Bill, and the proclamation of certain areas in addition to the registered ports where only the pearling crews shall be allowed to land for wood and water and the vessels to lay-up during the off season. In the N.W. District these areas are recommended to be at Ballangarra Creek, La Grange Bay, and Beagle Bay; the suggested limits and conditions applicable are to be found in the evidence given by Mr. Rodriguez [817-8], whose views, it is understood, are acceptable to many of the other pearlers.

Cygnet Bay has also been proposed, but is objected to by Mr. Hadley, of the Sunday Island Mission [1839-1845], who states that it would be no hardship for the boats to lay-up instead at Beagle Bay. With such areas and an officer of police in charge, assisted by a small patrol-boat up and down the coast-line, the present evils would be greatly minimised, because the pearling boats would then have to obtain wood and water by means of their own Malay crews independently of the assistance of the natives. No sacrifice should be considered too great to ensure these races being kept apart. The maintenance of a constable at La Grange Bay should be charged to the Police, and not to the Aborigines Department [72-4].

Your Commissioner further recommends an additional clause limiting the quantity of liquor allowed to be carried on anyone boat to two gallons, as in the Queensland statutes.

(4.) THE NATIVE POLICE SYSTEM:.

Strictly speaking, there are no native police, and but little system in the departmental supervision of the trackers. A few trackers have been handed over to the Commissioner of Police as prisoners [283], under 50 Vic., 25, Sec. 33, but he is not aware whether they are ever visited by justices [284] as is provided for by Sec.35 of the same Act. Otherwise they are got "the best way we can," generally from stations in the neighbourhood [281], and being engaged in their native country seldom leave it [294].

Trackers can come and go as they please, and are permanently employed if they like to stay [1480-1, 1593]: when the police want one they pick out what they consider is a good boy and put him on the list, but there is no signing on [1681]. During the course of his inquiry in the Northern and North-Western districts your Commissioner has only heard of one case where a tracker has been placed under contract [953]; this omission to enter into agreement is apparently unknown to the the Police Department [287, 289,. 290]. Trackers are paid nothing, though two shillings a day and in some cases three shillings are paid to the officer or constable of the station who provides the necessaries of life: the balance, if any, is handed over to the native [288]. So far, no evidence has been adduced to show that they ever do get any balance, while all the police witnesses exa mined on the matter have been found to be paid on the lower scale. Out of this, the officer in charge has to supply not only necessaries of life, but also clothes, and sometimes, where the "double-gee" plant flourishes, boots. There is no trackers' camp at the police stations, the tracker, if single, being supplied with accommodation in the stable or on the premises [296-8].

In the absence of any contract or other authority of office it seems almost questionable whether the tracker ought to assist in arresting, or be left in charge of, black prisoners, even while others are being arrested. The very fact of leaving black prisoners of trackers has on at least two occasions led to shooting, with fatal results ; one of these was in connection with the murdered gin referred to by the Resident Magistrate, Derby [1970]; the other led to correspondence (re death of Jumbi Jumbi) between the same gentleman and the Commissioner of Police wherein the former (3rd August, 1904) considered it undesirable that trackers should be armed. In the North-West they are still armed with Winchester rifles, That they are presumably used to firearms in these districts is reasonably deduced from the admission made by one of the police witnesses, that if the tracker is given a shot-gun he can find his own food [1583]. Your Commissioner recommends that these trackers be put under agreement with, a minimum wage, that their duties be strictly limited to trackers and horse-boys, and that on no pretext whatever should they be allowed to use firearms. It is not the business of a tracker to either arrest or be put in charge of any prisoner, white or black. A suitable uniform should be provided by the Police Department, in lieu of the garments at present supplied by the officers in charge.

(5). THE TREATMENT OF ABORIGINAL PRISONERS.

A. By the Police. Cattle-killing is the chief offence for which natives are sentenced in the Northern parts of the State; indeed, the proportion it bears to other crimes committed by them is about 90 per cent. [224, 225]. It is attributable to settlement in a new part of the country where the aboriginal race is rather numerous -- in the Kimberley districts, for instance [226].

Objections to European settlement from the natives' point of view - one which must not be lost sight of - are discussed when dealing with the question of Reserves, pp. 27/28. In connection with the arrest of aborigines accused of this crime, your Commissioner has received evidence which demonstrates a most brutal and outrageous condition of affairs. Not the least important of the links in this chain of evidence has been supplied by two native prisoners [1766, 1767] who, by a strange concatenation of events, proved to be the very men arrested by constables [1323-1465, 1466-1593] who had already been called before him as witnesses. The arrest of natives, and their subsequent treatment on charges of cattle-killing may be detailed as follows:-

When starting out on such an expedition, the constable takes a variable amount of provisions, private and Government horses, and a certain number of chains. Both he and his black trackers, as many as five of them [1479], are armed with Winchester rifles. A warrant is taken out in the first place if information is laid against certain aborigines, but when the police go out on patrol, and the offence is reported, the offenders are tracked and arrested without warrant [304.] Very often there is no proper information laid, in that it is verbal [1328-30]: when already out on patrol, there may be no information at all [1471]. Blacks may be arrested without instructions, authority, or information [1856-60] received from the pastoralist whose cattle are alleged to have been killed; the pastoralist may even object to such measures having been taken [1861]. Not knowing beforehand how many blacks he is going to arrest, the policeman only takes chains sufficient for about 15 natives [1336] ; if a large number are reported guilty, he will take chains to hold from about 25 to 30 [1485]. Chains in the Northern, not in the Southern, portion of this State [312] are fixed to the necks instead of to the wrists of native prisoners.

Authority for this is to be found in No. 647 of the Police Regulations [308]; which states that "the practice of chaining them by the neck must not be resorted to except in cases where the prisoners are of a desperate character, or have been arrested at a considerable distance in the bush; or when travelling by sea, they are near the land to which they belong, and it is necessary to adopt special measures to secure them. Even then the practice must not be adopted if it can be avoided." Children of from 14 to 16 years of age are neck-chained. There are no regulations as to the size, weight [309], mode of attachment, or length of chain connecting the necks of any two prisoners.

When the prisoner is alone, the chain is attached to his neck and hands, and wound round his body; the weight prevents him running away so easily [941-2]. According to the evidence of the Commissioner of Police [310], when there is more than one aboriginal concerned, the attachment of the chain would be to the saddle of the mounted police officer, but only when absolutely necessary; such an accident as a native neck-chained to a bolting horse has not yet happened, to his knowledge [311]. The mode of attachment of the chain round the neck is effected with hand-cuffs [1338] and split-links [1486, 1747]; the latter bought privately, i.e., at the expense of the arresting constable, from a firm in Perth [1487-8], and doubtfully [1489] with the knowledge or the Police Commissioner. The grave dangers attendant on the use or these iron split-links, and the difficulty of opening them in cases or urgency or accident, are pointed out [1067-1074, 1748]. The fact of the connecting chain being too short is also dangerous, because if a prisoner fell he would be bound to drag down the prisoner on either side of him ; yet the Wyndham gaoler has noticed the length or the chain joining two natives' necks to be twenty-four inches, the cruelty or which he remarked upon to the escorting police [1749]. As far as one witness can find out from police and natives, the chains are never taken off when crossing rivers and creeks [1759].

In addition to the neckchains, the prisoner may be still further secured with cuffs on his wrists (as your Commissioner has seen in photographs of constables escorting the chain-gangs), or on his ankles [1751]. Apparently unknown to the Commissioner of Police [306], chains are used for female natives [1159] not only at night, but sometimes during the day [1398-1400, 1409] ; these women are the unwilling witnesses arrested illegally for the Crown [1396-7]. The actual arrest usually takes place at daylight in the morning [1364, 1505] when the camp is surrounded, and occasionally the (armed) tracker is sent in by himself first [1353-4]. Accompanying the police may be the manager, or stockmen [1360], who have volunteered to come [1358], but as the manager does not prosecute [1641, 1942] and the stockmen are not called as witnesses, this voluntary action on the part of the station-employees may admit of another construction.

For instance, of the two constables examined, one takes no precautions at night to prevent the assisting stockmen and trackers having sexual connection with the chained-up female witnesses and yet supposes such intercourse to go on [1405-7]: the other never watches his trackers, who might carry on in this way, and never takes any notice of these things - it would have caused trouble if he did [1547]. It is noteworthy that these same two constables, together with two others, are charged by natives [1766-7] with intimacy with the women: the females brought in as witnesses are usually young ones [1248, 1653-5, 1955]. About six or seven is the largest number of guns in the arresting party [1363], perhaps such a quantity is accounted for by remembering that as many as 33 prisoners have been secured on the one occasion [1352, 1496].

The larger the number of prisoners and witnesses, the better, pecuniarily, for the police, who receive from one and sixpence halfpenny [1674] to two shillings and fivepence [1442, 1675] daily per head, or as it is called in the North-Western vernacular "per knob." This expenditure is spread over four departments [1895] as follows :-

- The Crown Law pays for the witnesses brought to and from the court,

- the gaols for sentenced prisoners in the police lock-ups,

- the police for prisoners from the time they are arrested until such time as they are convicted, and

- the aborigines for prisoners returning to their own country on expiry of their sentence [1890-4].

One constable admits making a profit [1458], a corporal considers that this allowance acts as a temptation to bring in a larger number of prisoners and witnesses than otherwise [1677], a civilian does not think so many cases would be brought before the courts if these allowances were not sanctioned [1249-1269], a Resident Magistrate has always been struck with the idea that this was the reason for so many natives being brought in at a time [1640], etc.

Your Commissioner is satisfied that the amount of purchased food, given to natives while on the road, usually constitutes but a fraction of the native food supplied, e.g., lizard, kangaroo, [1252, 1418, 1349, 1583, 1667a, 1766, 1767] : notwithstanding the challenged statement of the police [1495, 1983-6] meat is not usually sold but given to the police on these North-Western stations. The daily amounts allowed per head are charged for under the heading of Aboriginal Prisoners' Rations Account, and the Treasury Paymasters, etc., at Wyndham, Derby, and Hall's Creek [1594, 1670, 1889, 1987] have been called upon to supply items.

In less than three years up to date the amount so expended in the North-West districts of the State, North of Broome alone, has been £3,529 16s. 2d., and even this is incomplete, your Commissioner having reason to believe that certain of the claims are paid into private banking accounts, and so need not appear on the local Paymaster's list. Examples of the total amounts which certain of these constables, etc., have individually received are as follows :-

- - J. A. Caldow, £259 6s. 9d. since January, 1904;

- Wilson [1323-1465], £462 2s. 7d. between March, 1902, and October, 1903, and £192 14s. 7d. since July, 1904, it not having transpired how much he received between October, 1903, and July, 1904; - - J. Inglis [1466-1593], £29 17s. 1d. in October, 1902, and £165 16s. between April, 1903, and May, 1904;

- - F. W. Richardson, £121 7s. 8d. between October and December, 1903;

- - J. C. Thomson, £300 19s. ld. between March, 1901, and May, 1904, with £33 9s. 5d. since then;

- - W. Goodridge [1670-1705], £138 l0s. 8d. since April, 1903;

- - J. O'Brien, £138 5s. 9d. between November, 1901, and August, 1902;

- - A. H. Buckland, £215 12s. 6d., since March, 1903;

- - M. Mulkerin, £335 6s. since November, 1901 ;

- - J. P. Sullivan, £230 11s. up to September, 1904.

One of these recipients alleges that such moneys are paid into the mess fund at the station, so that the profits are indirectly shared by other police officers [1459]. The number of aborigines brought in being the great desideratum, each having a money value to the escorting officer, it is not surprising to find that little boys of immature age have been brought in to give evidence [1248], that children varying in age between 10 and 16 are charged with killing cattle [1752, 1034], that blacks do not realise what they are sentenced for [513, 1039], that an old and feeble native arrives at the end of his journey in a state of collapse and dies 18 days after admission into gaol [1754]. (It is only fair to state that with regard to the cattle-killing children just referred to, some of whom were found neck-chained in the Roebourne Gaol, that, as soon as the attention of the Executive was drawn to them by your Commissioner, they were released.)

Besides being half-starved [250-2], blacks are "hammered" on the way down [1766]. Any detentions on the journey in with the prisoners, or out with the witnesses, are also encouraged by this system of capitation fees. The Resident Magistrate at Wyndham complains of the constable's delay [1667c] in bringing down six alleged cattle-killers and the four witnesses; of the corporal and lock-up keeper detaining discharged prisoners, etc., unnecessarily [1067b].

Because rations are charged for to take the witnesses home again, it does not follow that they are escorted back; in some cases [1444-5, 1758] they are certainly not; in others, they may hardly have time to get to their destination before they are "rushed in" again by the police with another mob [1660, 1727]. It is no secret that the police say, if the ration allowance was cut down or taken away they would not arrest so many natives. By their own assertions, every native caught means more money in their pocket; reliable witnesses have heard such assertions made [1269, 1755].

At present there is nothing to prevent the constable arresting as many blacks as he chooses [1898], while there is no limit to the number of witnesses he is allowed to bring in with him [1899]. With a view to avowedly justifying their action in bringing these large batches of prisoners into court - as many as ten [1940] or fourteen [1637] at a time - the police necessarily take care to make absolutely sure of a conviction, and, unfortunately, the Criminal Code Amendment Act of 1902 is the means of putting a suitable weapon into their hands. By 2 Edw. VII., No. 29, Sec. 5, "If an aboriginal native charged before justices with any offence not punishable with death pleads guilty, the justices may deal with the charge summarily. But no sentence of imprisonment imposed on summary conviction shall exceed three years."

To secure a conviction- the accused are accordingly made to plead guilty at the muzzle of the rifle, if need be [1766-7]. At this your Commissioner is not at all surprised, considering his firm conviction in the truth of a statement made him by a native lately released from gaol, where he had served a sentence for cattle-killing, to the effect, that one of the batch of prisoners originally arrested with him was shot by the escorting constable in the forehead, the victim in question being very sick at the time. Owing to the informant's lack of proper pronunciation, your Commissioner unfortunately cannot absolutely identify the murderer's name, though he has reported the matter to the proper authorities.

With regard to the young women witnesses, their prostitution by the escorting police, the trackers, and stockmen, etc., who have aided in hunting them down, has already been referred to; partly for this reason and partly to gain their acquiescence in the subsequent court proceedings, their treatment on the way down, as compared with the men, is tempered with perhaps a little more mercy in the way of food and comparative freedom.

Though these women are allegedly as guilty as the men [1432, 1519, 1546], one constable states that he is acting under instructions in not arresting them [1519-1521]; on the other hand, they are chained [1398, 1159] or otherwise prevented getting away [1555-8] ; they are practically asked to turn informers [1433, 1568] ; they are never cautioned in the proper sense of the term [1377, 1428, 1514-1517] when giving evidence against their husbands, and thus do not in the slightest degree realise the harm they may be doing [1570].

The excuse made for bringing in these women at all is that the constable can get no other native evidence [1430], or that "the grown-up men are those that kill the bullock; there are no young boys in the tribes; the squatters have them all" [1566]. The accused male prisoners still less understand their position: On their arrest, which may even be before any evidence detrimental to them had been received [1374], they are asked (apparently without being cautioned) whether they have killed a beast [1378, 1530-1], but not necessarily informed with what they are charged [1379, 1532] ; they do not at the time thoroughly understand what the charge is, but might a few hours later [1390], evidently after the gins' evidence had been suborned.

The police tracker is the medium of communication, occasionally has to converse through a second interpreter [1388], and camps with the prisoners and witnesses before the case is brought into court [1272]. No witnesses are ever brought in for the defence [1424, 1564]. Furthermore, the pastoralist or station manager does not prosecute: he is generally very busy [1563] ; it is a matter of domestic economy, he would be only too pleased to prosecute if he could do so with a minimum of personal inconvenience [1607].

It is quite intelligible that such an individual's personal convenience should be thus respected; the liability of the accused to a sentence of three years' hard labour, possibly in neckchains throughout the whole of that period, is hardly worth consideration - it is only a "nigger." The Resident Magistrate, Wyndham, states, "I think, and. have seen it, that a man will plead guilty now for killing a beast some time ago: the native cannot separate two charges on two beasts, and will still have the same offence in his mind: if he kills a bullock once he will plead guilty to every subsequent charge of killing a bullock, no matter how often he will be charged with it [1651]."

Thus, all to the advantage of the prosecution, when once the native has been induced to plead guilty, there is no necessity under this Criminal Code Amendment Act of 1902 for any awkward questions being asked concerning proof of identity or ownership of the beast, the actual killing, eating, or alleged removal of the carcase. One witness who has brought about, or perhaps over, 100 natives into Court does not remember any who have been found "not guilty" [1446-7]; under the circumstances already detailed, this is no matter for surprise.

In two cases drawn attention to before the Commission where the accused pleaded not guilty [I938] they were of course remanded to Quarter Sessions; the charges were thereupon withdrawn on the application of the corporal of police on account of the expense of maintaining the witnesses.

Your Commissioner recommends the abolition of neck-chains and their substitution by wrist-cuffs, one prisoner's right hand being connected by chain to his neighbour's left. All the officers in charge of the three north-western gaols admit that by this method the transport of prisoners could be effected in safety. There should also be an alteration in the present system of allowing the police to draw so much "bloodmoney" for each native prisoner. If rations are purchased at stations or stores en route they should be charged for on vouchers.

B. By the Bench.- The Resident Magistrate, Derby, objects to the procedure already mentioned in the Criminal Code Amendment Act, in that he thinks it has resulted in depriving the aboriginal of one of his chances of assistance [1936]. His evidence on this and kindred questions is well worthy of perusal [1933-1966]. He is now altering the usual procedure, and has told the police that in future he would expect the aggrieved party himself-the pastoralist, etc., whose cattle have been killed - to prosecute in person; and that where such cases are of the nature that the Criminal Code is amended to cover, he will endeavour, on the ground of expense, to hold special sessions for them [1938].

He has also objected to the question being put to the native to show cause why he should not be committed for the particular offence; for by the time it is explained, he usually regards it as an opportunity to admit the crime. The Act of Parliament, however, directs that the question be put whether he has killed or not killed; and if a black commits the offence he will plead guilty, i.e., admit the offence. For this reason this witness does not think the question should be put, but he is forced to do so when dealing with the case under the Criminal Code Amendment Act [1952]. Of course, the same evidence which convicts an aboriginal with a plea of guilty would convict a European under a similar plea [1665, 1961]; but the latter is intelligent enough not to risk any unnecessary chances.

Blacks are charged conjointly in these cattle-killing cases [1439, 1571, 1637, 1939], as many as 14 at a time. The Resident Magistrate, Wyndham, has felt all along that the natives, first of all, do not thoroughly understand the charge against them, and that they do not understand the nature of the crime of killing a beast [1667a]. His fellow magistrate at Derby thinks that the blacks kill the cattle for the mere sport of it, although they may do so for want of food when the kangaroos (destroyed by the pastoralist on account of sheep and cattle) become scarce [1932].

Beyond what the Bench can do in the way of justice and fair-play to the aboriginal - and both at Wyndham and. Derby your Commissioner is satisfied that the present occupants have done their best under the circumstances - the accused usually has no one specially appointed to act in his defence, be it on a charge of cattle-killing or of murder. On the other hand, small amounts for this purpose have been expended by the Aborigines' Department [121-3].

In a case of murder, the depositions are signed and sent to the Attorney General, Perth, who decides whether the indictment is to be filed against the accused, when, where, and by whom. A Supreme Court commission is then issued for the trial, the Attorney General filing the indictment. It has happened that the magistrate holding the preliminary inquiry has been put in the unenviable position of acting under this commission as a Judge of the Supreme Court.

If a human being is being tried for his life, the least the State can do is to give the accused the fullest justice in its power, with a view to directing the jury to the best of its ability: the medical men placed in this responsible position, while conscientiously doing what is right, have, however, received no special training in the law.

Two Resident Magistrates are dissatisfied with the present system of trying savages for tribal murders: one believes in them managing their own tribal affairs [1668], the other considers there should be special laws and procedure for them [1962, 1974]. By the same section of the Criminal Code Amendment Act, and by the Justices Act of 1902, Section 32, which permits a Justice of the Peace to adjudicate by himself in the absence of another honorary magistrate within a radius of 10 miles, the terrible power is given to any of these justices of sentencing a native to three years, in addition to a flogging (Section 655 of the Criminal Code): fortunately, the whipping ordered under such circumstances cannot be carried out without the sanction of the Governor in Council. Not a single witness consulted approves of such a power being given to a justice [190, 906, 1140, 1633, 1933, etc.].

On looking over the warrants at the various gaols, your Commissioner finds that natives have been sentenced under such circumstances: e.g., four of these warrants were dated 8th May, 1903, and signed by D. W. Green, J.P., the Postmaster at Turkey Creek [1180-1189]. There is nothing to prevent a Justice sitting on a neighbouring Justice's grievance, and although he may not be an interested person within the meaning of the Act, he is actually interested in the principles involved [1974].

It is thankful to learn from the Broome gaoler that sentences for cattle-killing are not quite so long as they have been in former years [517]. On the other hand, the Chief Protector suggests justification for severe sentences (three years) for this charge, on the grounds that other and more unlawful means might be taken against the native [I 88-9]: surely the Executive would not hesitate to arraign the pastoralist for murder?

At Wyndham, when boys aged from 14 to 16 have been charged with cattle-killing, the Resident Magistrate has cautioned, convicted, and released them without imprisonment [1657-8]: at Derby, when a young boy comes into court the Resident Magistrate prefers to give a small sentence and to find him an employer [1953].

At Hall's Creek the whole brutality of the present system is brought into prominence when the acting Resident Magistrate sentences a child of 10 years of age to six months' hard labour for "that he did, on or about 10th September, 1904, near Cartridge Springs, unlawfully kill and carry away one head of cattle, the property of S. Muggleton, contrary to statute then and there provided" [1752]. The same magistrate has sentenced another infant of 15 to nine months for killing a goat [ 1753], and at least eight other children, between 14 and 16 years of age, to two years' hard labour for alleged cattle-killing. As already mentioned, four of the latter met with by your Commissioner in the Roebourne gaol have since been released.

Your Commissioner recommends a modification of Section 5 of the Criminal Code Amendment Act, and invites the Crown Law officers to consider the advisability of allowing the acting Resident Magistrate at Hall's Creek to continue in office.

So far as tribal homicides are concerned, no action should be taken in the courts or otherwise, unless the killer has become such a terror or "bully" that his clansmen are afraid to deal with him ; owing to length of contact with civilisation, he ought to have known better ; or the killing has taken place in the neighbourhood of close European settlement. Even then, unless very particular circumstances demand it - and this would be for the Chief Protector to decide - the culprit should be deported and detained in another district, in employment if necessary, under the provisions of Section 15 of the proposed Bill.

C. In the Gaols.-Your Commissioner visited the gaols at Carnarvon, Broome, Roebourne,

and Wyndham, and is able to place on record his high appreciation of the humane supervision and considerate treatment exercised by the gaolers over their aboriginal prisoners. Approximately, there are about 300 native prisoners in the gaols throughout the State [223].

Two very degrading and yet remediable features of the prison system are the neck-chains, and their continuous use - morning, noon, and night - usually throughout the entire period of sentence.

Though the Comptroller General of Prisons has no legal authority for using neck-chains at all [241], and there are no regulations as to weight, size [244], and mode of fixation (Yale locks, split-links, or cuffs, etc. [423]), he has nevertheless given instructions for their employment in the case of natives [495-499]. His predecessor gave similar instructions [411]. Except in times of sickness, etc., the prisoner is neck-chained from the day he comes into gaol until the day he leaves it, sometimes from two to three years [525] and upwards, according to sentence.

There appears to be differences of opinion as to whether neck-chains should be leather-covered or remain bare [246, 421, 489, 521, 1007, 1712-3] so as to minimise chafing, etc. At night in the Roebourne gaol the chains are fastened to rings in the wall [1021], etc.: at Wyndham one out of every group of three (neckchained together) is chained by the ankle to a ring-bolt in the floor [1719]; at Carnarvon, the chains connecting one prisoner's neck-chain with another's serve to fix them around the central post supporting the roof [425].

Still neck-chained, the native prisoners work outside on the roads, etc.: they thus work about eight hours' daily at Broome [526], seven and a-half hours at Carnarvon [442], under six hours at Roebourne [1047], and somewhat longer at Wyndham [1730]. Though the number of hours is fixed by the Gaols Regulations No. 263, slight alterations have to be made here and there in the summer-time [444, 1049, 1731]; at Carnarvon there is the medical officer's standing order that all prisoners are to be brought into gaol when the thermometer stands at or over 98 deg. in the shade [443].

On the other hand, at Broome there is no distinction made between winter and summer months; in the gaoler's opinion the hours here are too long in the latter season, and in some cases the prisoner's health has been affected in the way of sunstroke [527-8]. All the gaolers in the North-West are in agreement that the present system of neck-chains could be abolished, and suitably replaced by wrist-cuffs, one prisoner's right hand being connected by chains to his neighbour's left [545, 1061, 1736]; that a shorter connecting chain could be used [546, 1062, 1737] : that more freedom of movement would be allowed [546, 1062] : that the present employment outside the prison walls would not be interfered with [549, 1063, 1739]; and that, when necessary, the transport of prisoners, thus chained, could be effected in safety [549, 1063, 1738]. This method of chaining natives does not appear to have been known to the Comptroller General of Prisons who, in correspondence with the Aborigines Protection Board, expressed the wish to see his way to abolishing chains, but stated that he knew of no method of retaining the aboriginal except within walls [255].

Your Commissioner was certainly surprised to find that such walls, except at Roebourne, had not yet been built. Chains could be abolished in the case of aboriginals working inside the prison, and at night, if the gaols were properly built [505]; as temporary measures, - all that would be required is a cheap iron fence at Broome and Wyndham, and a chevaux-de-frise at Roebourne. By 50 Vic., No. 25, Section 33, the Governor in Council may place an aboriginal prisoner "under custody of any officer or servant of the Government" who is thus responsible, and the prisoner is deemed to be in legal custody, wherever he may be employed or detained. Though this has been done within the last twelve months the Comptroller General does not consider the system a good one [264-273].

So far the rules and regulations provided for by the Act, for the employment and safe custody of such prisoners, are conspicuous by their absence [275]. An aboriginal prisoner is being lent out to a Resident Magistrate on doubtful legal authority [402-7]. Others, on the instructions of such an official [484, 1709, 1710], are labouring outside the prison wa1ls on public and municipal works [261] and for local roads boards [1709]. In return for the work done for the Carnarvon Municipal Council they get a little tobacco, which, it is believed, is paid for out of the Mayor's private pocket [429]. Although they may be improving the value of local and municipal property, no payment is received by the Government towards reducing the expense of their keep, or return-home journey when liberated, or even of covering the cost of their clothes which, on expiry of their sentence, the Aborigines Department has to provide [84]. Furthermore, the Gaols Department Regulations Nos. 264, 266 preclude any gratuity being given, on release, to an aboriginal - another colour distinction - although he may be as civilised and appreciate the value of money as well as his European fellow-captive.

With regard to long sentences passed upon native prisoners, they are not considered beneficial. The blacks are far better in their uncivilised than semi-civilised state, and are a great deal of trouble after they come out of gaol [1863]. It does not do them the least bit of good, and does not stop them from killing cattle, the same blacks being brought before the Court again and again [1604, 1168].

Your Commissioner has also been informed that, according to the prison dietary, their taste for beef is still further cultivated. When blacks have been away from their native homes so long, they seem forgotten when they return; their tribes will have very little to do with them, and they often commit further crimes because in the meantime their women have been taken [1041, 428].

It is doubtful whether the aboriginal prisoner understands his position [519], or knows that he is committing an offence when he tries to break gaol [533]. One gaoler is of opinion that amongst the twenty blacks in his charge sentenced for cattle-killing, not one really understands what he is there for [513]. Another, with seventy-two prisoners, thinks that about one-third of them know [1039]. Another states that when he took charge a great number of the prisoners were "myalls", and their idea was that they were there for road-making, but that as they became educated and get to gaol so often they now realise that it is for cattle-killing [1726].

In the Kimberley District due care does not seem to have been always taken as to the identity of prisoners when first brought to gaol. Carelessness almost amounting to criminality is responsible for longer sentences having been exchanged for shorter ones, and for one case where a prisoner having two native names has really received two sentences on the same charge, while a fellow prisoner's name was on no warrant at all [1765]. When once in gaol, however, due precautions are taken in the way, of attaching numbered metal tags to the chains [433, etc.].

The transfer of prisoners from one gaol to another is carried out under the escort of the police, and not of the warders, who know their prisoners and understand their temperaments better [541-3, 1064-5, 1744-5]. Alone at Wyndham there would appear to be a valid reason - delay in the return of the warder - why this work should not be always undertaken by officers of the Gaols' Department [1746]. Certainly on two occasions, owing to running short of handcuffs [1740-1], two batches of prisoners, twenty in each batch, were received at Roebourne bearing neck-chains fixed with split links; evidence was taken on the difficulty in unloosening such fastenings, and the terrible risks run on board the steamer conveying them [1067-1075]. In spite of Police Regulation No. 647, it would appear that during transport on the steamer the neck-chains are not removed.

Flogging of natives is not approved by the gaolers at Broome [583] and at Roebourne [1057-9]; at Wyndham the officer in charge approves of it in certain cases, say for assault on a warder, although such has never occurred [1733-4]. The Resident Magistrate at Marble Bar does not think whipping as cruel as imprisonment, than which it has a more deterrent effect; he would have ordered it oftener only for public opinion being so much against it [906]. The flogging of a native is referred to the Comptroller General of Prisons for approval before being carried out; a merciful provision.

Your Commissioner recommends the abolition of chains of all description within the precincts of the gaols, the insecure condition of which should be remedied without delay. In English prisons, e.g., Portland, chains are used only in punishment for the most serious offences - assaults on officers attempts at escape, and persistent insubordination or refusal to work: the irons consist of rings for the ankles and two chains which are linked together and fastened to a belt; their weight varies from six to ten pounds, and when a prisoner is put into them he wears them constantly day and night for the period of his punishment, for which the maximum is six months.