Dadawarra from Mungullah, WA declares his sovereignty

Dadawarra says a 1,041 page Federal Court judgement on native title in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia seven years ago affirmed him as the sovereign ruler of the Commonwealth, extinguishing the Crown's sovereignty at the same time.

He argues through a complex marriage of Western Australian and national legislation, and ancient Aboriginal customary law - may actually hold water, with cryptic comment from the Federal Court doing nothing to dispel it.

By Darcy Hay EastWest 28 January 2016

Dadawarra

Dadawarra says a 1,041 page Federal Court judgement on native title in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia seven years ago affirmed him as the sovereign ruler of the Commonwealth, extinguishing the Crown's sovereignty at the same time.

He argues through a complex marriage of Western Australian and national legislation, and ancient Aboriginal customary law - may actually hold water, with cryptic comment from the Federal Court doing nothing to dispel it.

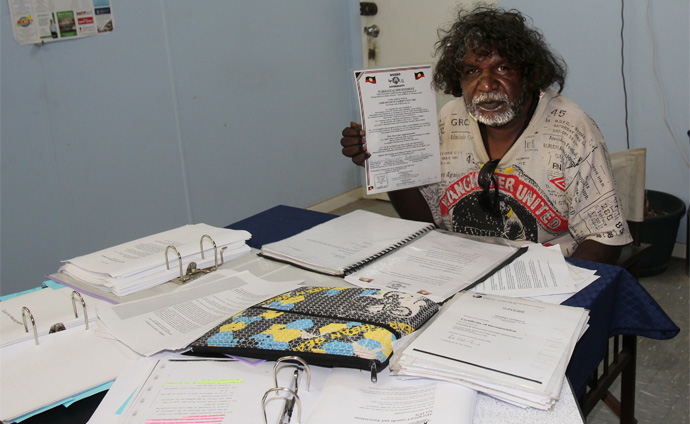

In the impoverished Mungullah Aboriginal Community, on the outskirts of Carnarvon, Western Australia, Dadawarra sits in his house, three open lever-arch files and hundreds of pieces of paper on the table before him.

Closer inspection delineates legislation - like the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, or the Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority Act 1972 - from letters, signed by figures such as the Western Australian attorney-general, the state's Aboriginal Affairs minister, Land Council chief executive officers, and anthropologists.

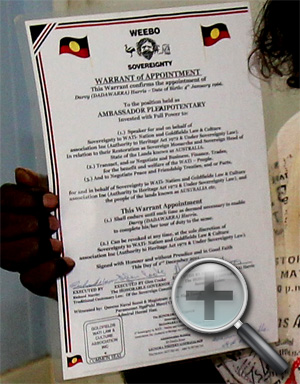

Amongst the paperwork is a striking, full page black-and-white printout.

It shows a wati, or fully initiated Western Desert man, holding several engraved wooden boards.

Dadawarra calls them sceptres, and they are integral to his argument, and to his existence.

"Our sovereignty was officially recognised 1972, but the 2007 court case confirms it," he says.

"Our sceptres, which they protected under the Aboriginal Heritage Act, define our law - no sceptres, no sovereignty.

"Our sceptres have survived for thousands of years, and are still there; they're protected by parliament now."

These 'sceptres' embody all law laid down in Tjukurrpa, popularly known, in broad terms, as the Dreaming.

Former director of University of Western Australia's Berdnt Museum of Anthropology John E. Stanton, who has worked with Western Desert people since the mid 1970's, described the boards - known as daragu or tjurunga - as being 'like the soul of a fully formed person'.

"They have been likened to 'keys' to the Tjukurrpa, and also as 'title deeds' to the land," Dr Stanton says.

"As such, they are central to the assertion of Law in the Western Desert - they are dangerous in the wrong hands, even accidental breakage could result in death.

"They must be looked after; they are the 'crown jewels' of Desert Law and are treated with great respect and veneration."

Dadawarra with some of the paperwork that he has amassed in the pursuit of proving his claim to sovereignty

Dadawarra is the custodian for sceptres intimately linked to a site east of Western Australian ghost town Agnew, named Weebo.

Weebo was the first place to be protected under the state's Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, and Dadawarra says it is very different to other sacred sites.

He says it's where creation occurred, is where all customary law derives from, and is thus the paramount sacred site for all people within the Western Desert Cultural Bloc.

The Bloc spans an area of 600,000 square kilometres across the interiors of Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory, with 40 largely mutually-intelligable dialect groups spoken within that boundary.

Dadawarra compares Weebo to the Vatican, stating that while all churches are holy to Roman Catholics, the Vatican holds ultimate sway.

"Weebo is like how they say, all roads lead to Rome," he says.

"When you go to the Northern Territory, they've got the sceptres there too, but Weebo overrides that, because of the Law; it's the top site, number one.

"It's like the Commonwealth overrides the State - Weebo is the sovereign sceptre.

"Other senior men can look at it, they can touch it, but they can't own it, I've got the ownership."

Custodianship over Weebo runs in Dadawarra's family alone, and he is the only person who exercises customary ownership, or ngurra, over the site.

Dadawarra's ownership is very distinct from the well-known native title process.

Under native title, bundles of rights and interests over land - which can be extinguished on an individual basis by the Crown - are afforded to Aboriginal people and groups who successfully demonstrate ongoing traditional connection to the land.

Dadawarra's tenure over Weebo comes from the Western Australian Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority Act 1972, which not only established the state's Aboriginal Lands Trust, but created today's Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

520.8 hectares at Weebo is held under the Aboriginal Lands Trust, with 'exclusive use and benefit' vested in Dadawarra and other wati under Section 32 of the Act, following a decree from the state's Governor.

But to find his claim to sovereignty relies on the protection afforded to Weebo, and to the sceptres, under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972.

The Act's first page summarises it as making " ... provision for the preservation on behalf of the community of places and objects customarily used by or traditional to the original inhabitants of Australia or their descendants."

'Sacred objects' are referred to many times in the Aboriginal Heritage Act.

Dadawarra says this wording not only represents an ignorance of the sceptre's purpose, but a mistranslation of immense significance.

He argues that it's impossible to preserve Weebo and its sceptres without enshrining a preservation of their meaning - and that, under customary law, the inalienable meaning attached to both the sacred site and its sceptres is absolute sovereignty.

"The protection that they assented through parliament wasn't just a piece of paper - when the Heritage Act received the Royal Assent, it means the sceptres received the Royal Assent with it," he says.

"The governments and anthropologists in those days said the same thing - 'that's a sacred object', they didn't realise it was a sceptre.

"The Act didn't say they were sceptres, it said they were sacred objects - the government used a different language, they should have been saying it was a sceptre.

"They are the element of sovereignty - when you have sovereignty, you've got to have the essential elements that constitute sovereignty, and sceptres are one of the main ones.

"Weebo, the people and our form of government are the others, and we've still got all of them.

"When you look to the sky, how far your eyes extend, that's how far our law extends - and in our law, the state doesn't exist.

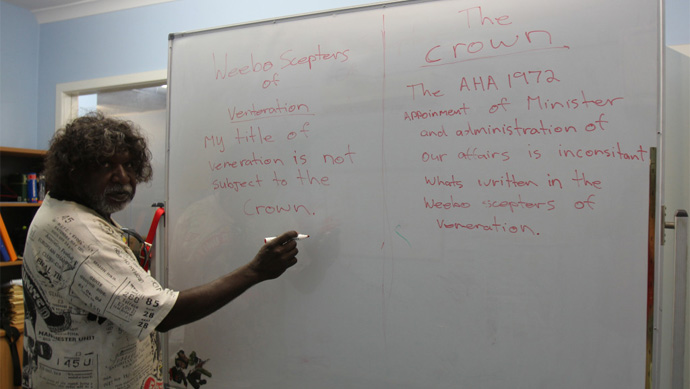

Dadawarra explains his sovereignty claim through a table that contrasts - and shows the overlap between - Commonwealth and traditional Western Desert channels to sovereignty

There is evidence to suggest not.

"Under my Law, how can I recognise you? This was set up before Captain Cook came here.

"Do the roots of English law recognise me, recognise wati?"

Dadawarra's declaration of annexation, given to Western Australian Attorney-General Michael Mischin in December 2012, drew a blank.

A hand-signed letter from Mr Mischin, dated April 11 2013, responds simply - "It is noted that the 'Declaration of Annexation' has no legal effect."

But then again, perhaps the devil is in the detail.

Dadawarra argues Justice Lindgren's 2007 rejection of The Wongatha People vs. Western Australia native title claim, which was put forward by Goldfields Land and Sea Council, is an acknowledgement of his sovereignty.

As chairman of the Goldfields Wati Law and Culture Association, Dadawarra staunchly opposed the claim, testifying against it on grounds of his sovereignty in a Federal Court sitting in Kalgoorlie over the course of 100 days.

With 160,000 square kilometres of land pooled under eight sub-claimant groups, and hundreds of Aboriginal people called to give evidence, the Wongatha hearing was, at the time, the largest native title claim to go before the courts.

Dadawarra argued in court that the claimants were not authorised, under the customary law he holds sovereignty over, to apply for native title.

Indeed, he says had the claim succeeded, the floodgates for mining and land development would have been opened, and watis would have been 'dispossessed' from sacred sites.

"Native title was a way around the Aboriginal Heritage Act, it was like a loophole to go around sovereignty," he says.

"Native title is not a land tenure system, it only gives you rights to use somebody else's land.

"When native title came onto my land, it brought us into the courts, into the argument, and we told the court, 'this is our land, you have no jurisdiction there - your jurisdiction legally ends at my jurisdiction'.

"The Federal Court was unable to deal with it, because of that."

Justice Lindgren's reasons for dismissing the claim were varied.

For instance, he found the claimant groups made a 'fatal flaw' in applying as groups, where traditional custom did not recognise group ownership.

However, in his official statement of reasons given, Justice Lindgren accepted Dadawarra's testimony, appealing to section 61(1) of the Native Title Act in stating the " ... purported authorisation process had not been undertaken in line with traditional laws and customs relating to such matters".

Goldfields Land and Sea Council were approached for comment on customary authorisation, but failed to respond.

Dadawarra interprets Justice Lindgren's acceptance of his testimony - rendered legitimate by traditional laws on authorisation - as an acknowledgement from the Crown that customary law has validity in the Australian court system.

He says that, by projection, his customary claim to sovereignty must similarly be recognised.

"The decision was about who holds the proper tenure here - the court made a decision as to who really owns the land and who's sovereignty still continues, and it was a very big landmark, beyond a landmark," he says.

"I couldn't hear properly what was said, because they interpret things in their own language, and have their own meaning, but under our Law, the meaning is clear.

"When the Crown acknowledged my Law, they acknowledged my sovereignty, and because of this, the sovereignty of the Crown has been extinguished.

"Their sovereignty doesn't exist in our customary system, there's no other sovereignty that can exist in our customary system - how can I recognise the Crown if it's not recognised in my sceptres?"

In an informal public summary of the case, Justice Lindgren admitted the case exposed him to what he considered to be an 'unsatisfactory state of affairs in the native title area', but stuck to the position that Crown sovereignty reigned supreme.

"Perhaps the heart of the problem is that the legal issue that the Court is called upon to resolve is really only part of a more fundamental political question," he wrote.

"One matter is that expectations are created.

"The Indigenous people in this case are the descendants of those who lived in Australia for tens of thousands of years - one witness said words to the effect, 'if I cannot claim native title in this area, where can I claim it?'"

"The implication is that a Judge will surely have no difficulty in seeing that the witness must have native title somewhere.

"The fact is, however, that since the establishment of British sovereignty, in the case of Western Australia in 1829, there has been a new sovereign legal system, the laws of which are determinative of legal questions."

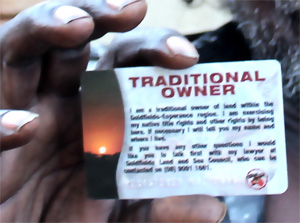

Dadawarra with his registration card of traditional ownership, and a 'seal' he bought to stamp documents with his mark of sovereignty

Dadawarra Traditional Owner Card

The story might end with this post-modernist cultural gridlock - ie, the conundrum over which sovereignty exists when each system of sovereignty, according to their particular cultural norms, denies the existence of the other sovereignty - were it not by a cliff-hanger from Federal Court spokesman Bruce Phillips.

When asked to simply confirm or deny whether the Crown's sovereignty still exists after the Wongatha claim's resolution, his answer gave none of the certainty over tenure invariably sought by mining companies, pastoralists and other respondents to native title claims.

"The Federal Court declines to comment - the judgement speaks for itself," Mr Phillips said.

With about 17,000 pages of transcribed evidence, 8087 combined pages in submissions and 2,817 pages in expert's reports to get through before tackling the 1041 page judgement, it'll take a good degree of homework before one can make a fully informed interpretation of just what it is that the judgement says, and whether Dadawarra's claims are valid.

Dadawarra has no doubts on the matter though, and says he wants his stake on sovereignty aired for all to see.

"We had our day in court, and we want to move on from that decision, and look into a treaty - I think, at this point, we're at the door to a treaty," he says.

"I don't want to end up like Mabo, I want to live to see what I've achieved."