Survivors of 'forgotten' Woolwonga tribe acknowledged 130 years after 'extermination'

From left, Tara May, Maxine Kunde and Tellisha, Jayde, Glen, Leroy and Rob Hopkins at home in Darwin.

(Picture: Amos Aikman The Australian)

The Woolwonga were said to have been exterminated in 1884 at Burrundie about 200 kilometres south of Darwin in reprisal for spearing non-Aboriginal miners.

But about four years ago an 1899 census document was found showing at least one had survived.

James Purtill ABC 25 September 2014

Expand/Enlarge

(ABC News: Lynette Hopkins)

Exactly how the Aboriginal girl known as Jennie survived the massacre of her people - the "warlike" Woolwonga of the Alligator River near Katherine - is not known.

But 130 years later, her descendants will gather on what they say is their land to declare the lost tribe returned and call for official recognition.

The Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Senator Nigel Scullion, will unveil a plaque at the event on Saturday.

The Woolwonga were said to have been exterminated in 1884 at Burrundie about 200 kilometres south of Darwin in reprisal for spearing non-Aboriginal miners.

But about four years ago an 1899 census document was found showing at least one had survived.

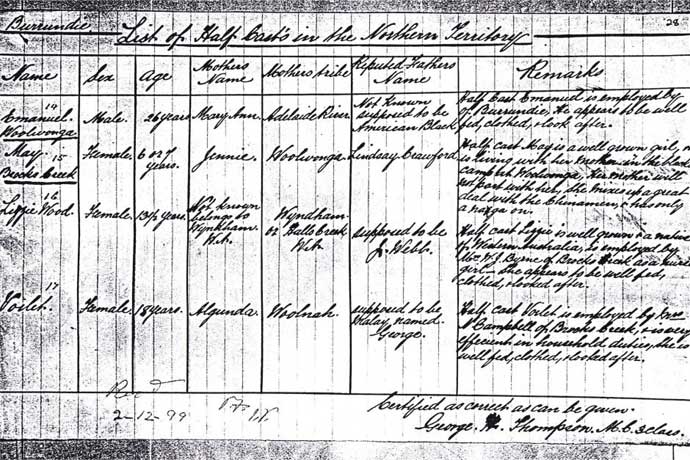

According to the List of Half Casts (sic) in the Northern Territory, Jennie of the Woolwonga tribe had a daughter, May, in 1889. May took the surname of her father, the station manager Lindsay Crawford.

Hundreds are expected to attend the gathering on Saturday, and dozens of these will come from Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, according to the Woolwonga Committee's Mark Baumgart, who is travelling from Queensland.

"We're making a statement that we're descendants of a proud people," he said.

"We're not extinct. We may have been fragmented and dispersed but we've now come back around full circle.

"We're passing on the baton of research to our younger ones.

"It's not along the same lines as the non-indigenous remembrance of the Anzacs but it's similar. It's a deeper sense of belonging to the area.

"We still have the overlay of spiritual connection regardless of whether we have land rights or not."

We want land rights: Woolwonga chairperson

But Woolwonga Committee chairperson Lynette Hopkins said the group would demand shooting and fishing rights on the land.

"It'd be the start," she said. "Why wouldn't you, if we became recognised? You can't be extinct when you've got people all over Australia coming that've got links to family groups from the Woolwonga.

"We're not chasing the big royalties and all that stuff. We want recognition that this is our land so we can go out there and just fish and hunt."

Enlarge

'Half casts in the Northern Territory'

(ABC News: Lynette Hopkins)

A spokesman for the Northern Land Council, the native title representative body for the northern region, said there had not yet been any native title claim to the affected land.

"NLC has received from the committee various documents which they say asserts their native title rights," he said.

"We expect to do the anthropological work in the next year."There's been no decision yet on native title to lands they're claiming."

'We're a tribe, we're something, but what are we?'

Mr Baumgart, 52, a Woolwonga Research Committee member, stumbled upon the 1899 census document soon after it was made available through the Bringing Them Home Report into the Stolen Generations.

He had previously learnt his great grandmother, May Crawford, was of Aboriginal descent.

The single line of census entry written in cursive copperplate script established May Crawford was Jennie's daughter, and that Mr Baumgart was descended from the Woolwonga.

"As soon as I saw that, I must admit, I'm a bloke but I cried," he said.

"It's very important for me. My objective in finding out our heritage is more from the heart and soul. I'm not looking for anything other than linking and connecting with what my heritage is and what my people were and are today."

Meanwhile, in Darwin Indigenous elder Maxine Kunde, as well as Glen and Lynette Hopkins, were following a paper trail of archival documents.

Enlarge Image

(ABC News: Lynette Hopkins)

"The thing that started it all was the young ones," Mrs Hopkins said. "They're coloured. They say, 'we're a tribe, we're something, but what are we?' The old people in the old days kept everything secret.

"They never talked about it because it was shame.

Mrs Hopkins wrote to the South Australian Museum - which has the world's largest collection of Aboriginal cultural material - asking for more information.

"They sent me back these references. I saw this one that said 'Woolwonga language and totems'. I thought, oh my God. It said it's at this institution down in England."

She wrote to thee Anthropological Institute of Great Britain which sent her the requested document.

"When I got it back it just blew me away. It had all our totems, drawings and language. Everything on the Woolwonga," she said.

The Woolwonga Committee held its first meeting in 2010. Over the next few years word spread and more distant family came forward.

"In the last three months it's just exploded," Mrs Hopkins said.

Lynette's husband, Glen Hopkins, is a great-great grandson of Jennie. He said the active pursuit of Indigenous heritage contrasts with his experience as a young man, when he had to hide the fact he was Aboriginal.

Lynette Hopkins (Image:ABC)

He grew up in the 1950s before universal Aboriginal suffrage, when only certain Aboriginal people had been given the right to vote, go into hotels or send their children to school.

These people were given special "exemption certificates" known as "dog tags".

"During the war, because of the White Australia policy, it was fashionable to be anything but Aboriginal," Mr Hopkins said.

"I was more accepted if I was a Kiwi or something like that."

More than 50 years ago in Kununurra in remote Western Australia, Mr Hopkins was questioned by the police while drinking at a hotel.

He had no "dog tag" allowing him to drink.

"If I was an Aboriginal he would have locked me up," he said.

"The person serving me could have been in trouble for supplying an Aboriginal with alcohol."

But at the last moment a fellow drinker interrupted.

"She told the cop, 'He's a Fijian pom'. So the cop looked at me and left me."

Mr Baumgart grew up in Darwin with his mother telling him and his seven siblings they were Indonesian.

"It wasn't ever talked about," he said. "Even talking with aunties before they passed way they couldn't give us anything. There was a feeling the Aboriginal side of things was suppressed in the early days.

"Even my own mother never really talked about it. She had us believing as young kids we were Indonesian.

"If you look back in history a lot of migrants were pretty much in the pecking order above Aboriginal people in Darwin."

Unveiling Of a Plaque To Commemorate The Woolwonga Tribe Massacre 27/l09/14 (Image: Flickriver)

Heritage hunt sees bloody past give up secrets of Australia’s ‘lost tribe’

Amos Aikman The Australian 10 September 2014

It was one word shining through the archives that gave Glen Hopkins and Maxine Kunde their first hint they could be descended from a forgotten tribe.

Like many members of Stolen Generation families, they knew little about their heritage. Both living in Darwin, both married to non-indigenous partners. Mr Hopkins had been told he had Gurindji on his father’s side, but little more.

Then, about four years ago, a relative trawling through documents made available after the Bringing Them Home Report stumbled across census and marriage records from the late 1800s.

There, alongside their great-great-grandmother’s name, was the name of her tribe: Woolwonga. Woolwonga. Suddenly, both knew a little more about themselves.

At first they were elated, then confused. The term Woolwonga — or Wulwulam, its equivalent — elicits blank stares from many people in the Burrundie region, about 225km south of Darwin, where it originates.

That is perhaps because so many “warlike” Woolwonga were killed, in part in retribution for the so-called Copper Camp killings of three non-Aboriginal miners in 1884. The history is murky and fashioned to suit its tellers, but makes grim reading.

A report of an 1886 inquiry quotes a police officer describing an encounter with 20 to 30 Aboriginal people: “None of those who took to the water were known to have got away, and I believe the natives have received such a lesson this time as will exercise a salutary effect on the survivors.”

Piece by piece, however, Woolwonga heritage is starting to emerge. There are photos of proud Woolwonga people with ceremonial scars, and other more recent evidence firming the links to surviving families. An anthropological report found in Britain depicts Woolwonga drawings.

Now Mr Hopkins, Ms Kunde and their extended family are seeking recognition and rights over what they believe is their land. “I just want to be accepted as definitely from the Woolwonga tribe,” Mr Hopkins said. “If we don’t come forward then our history is going to be lost.”

Ms Kunde says she wants the struggle to come to terms with her Stolen Generations heritage to be over.

Jayde Hopkins, 17, one of Mr Hopkins’s grandchildren, says gaining recognition is important, so she knows where she belongs.