Push to recognise social disadvantage in sentencing

(Image source: Tracker)

Natasha Robiinson The Australian 2 August 2013

A key concession by crown prosecutors that the impacts of social deprivation do not reduce over time has prompted the Human Rights Commission to withdraw its intervention in the High Court case of William David Bugmy.

Criminal lawyers in NSW and Western Australia are gearing up for their attempt next week to convince the nation's highest court that any significant history of alcohol-driven social disadvantage should be explicitly taken into account in the sentencing process.

The Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT is arguing the case of Bugmy, a 31-year-old Aboriginal man from Wilcannia, in the far west of NSW, and the Aboriginal Legal Service of WA is representing 35-year-old Ernest Munda, an indigenous man from a remote community near Fitzroy Crossing.

Both cases centre on the relevance to each man's sentence of the common law Fernando principles, laid out in a 1992 judgment of the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, R v Fernando, which dealt in particular with alcohol abuse in Aboriginal families and its associated "grave social difficulties".

The Bugmy and Munda cases are being keenly watched in the midst of a joint campaign by the Law Institute of Australia, the Australian Bar Association and Aboriginal legal bodies to reduce the alarming over-representation of indigenous offenders in state prisons.

The High Court's judgment in Bugmy and Munda could pave the way for recognition in the sentencing process of the impacts of chronic disadvantage in the lives of Aboriginal offenders.

The Australian Human Rights Commission had intervened in the Bugmy case, seeking to make representations on the relevance of the Fernando principles, but that intervention was formally withdrawn after recent submissions filed by the crown which acknowledged the continuing relevance of the NSW Fernando judgment.

Bugmy seriously assaulted a prison guard in January 2011 while on remand for violent offences, blinding the guard after pelting a pool ball which hit the prison officer in the eye.

Bugmy had a criminal history which stretched back to when he was 12, and had grown up in desperate circumstances in a violent home and later, multiple foster placements, and with very little formal education.

He had chronically abused alcohol from an early age and had mental health issues.

The Aboriginal man's original sentence of six years and three months was later increased by the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal to seven years and nine months.

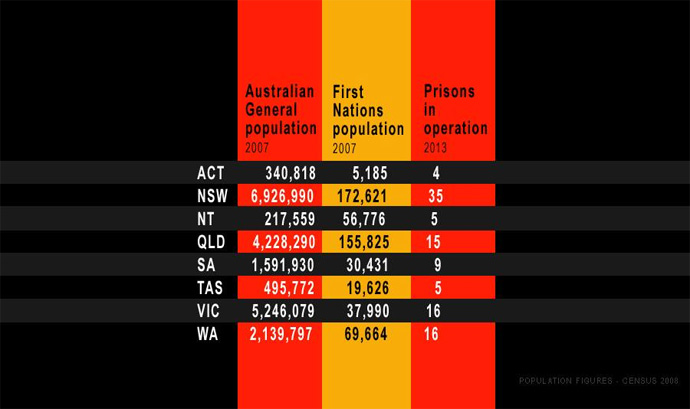

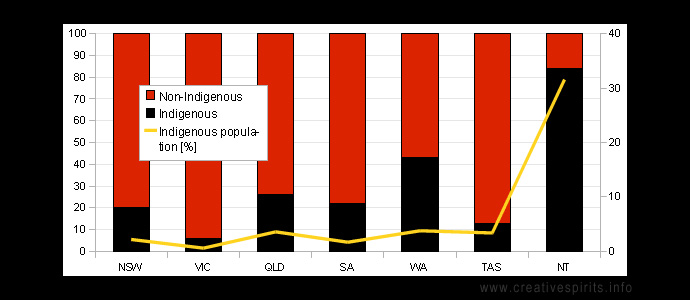

As the chart above shows Indigenous people represent on average 17% of the prison population

except in Western Australia and the Northern Territory where they account for 43% and 84%.

See: Aboriginal prison rates - www.creativespirits.info

Prosecutors had maintained during their appeal of the adequacy of the original sentence that Bugmy's case should not have attracted the benefit of the Fernando principles as the offender's social background was irrelevant to the prison assault.

And the judge hearing the criminal appeal, Clifton Hoeben, said in relation to the Fernando principles that, "one can't help wondering how many times one can cash that cheque before it runs out", arguing that "with the passage of time, the extent to which social deprivation in a person's youth and background can be taken into account, must diminish".

But in the latest crown submissions, prosecutors did an about-face and agreed with Bugmy's lawyers' central argument that: "The effects of profound deprivation do not diminish over time and their relevance should not be constrained".

"The respondent does not dispute that proposition," the crown's submission said.

"It is obviously correct that the systemic and background factors, particularly the extreme circumstances of deprivation - to which Fernando refers - remain significant and should not be discounted or given less than full weight in any sentencing exercise affecting the offender."

The Fernando principles provide consideration for the "endemic presence of alcohol within Aboriginal communities" and the "grave social difficulties faced by those communities where poor self-image, absence of education and work opportunity and other demoralising factors have placed heavy stresses on them".

Bugmy's lawyers have argued that in the past two decades, Fernando has been incorrectly interpreted in case law.

The High Court appeal in the Western Australian case of Munda argues along similar lines, alleging that the WA Supreme Court and WA Court of Appeal have adopted a limiting approach to the Fernando principles which "diminished the status of (Aboriginal) socio-economic deprivation as a mitigating factor" in sentencing.

Munda was convicted of manslaughter after a violent and sustained assault on his wife at a remote community near Fitzroy Crossing on July 13, 2010.

The then 32-year-old offender was heavily intoxicated at the time.

Munda's lawyers are also challenging the weight given to factors of tribal punishment in their client's case.

It is the first time the High Court will have considered the relevance of Aboriginality and social disadvantage in criminal sentencing since the 1982 case Neal v The Queen.

That case laid down what became known as the "substantial equality principle" that the same sentencing principles are to be applied to every case regardless of race or identity, but taking into account "all material facts including those facts which exist only by reason of the offender's membership of an ethnic or other group".

The Bugmy and Munda cases will be heard in Canberra on Tuesday.

Too many, and the number's growing

Indigenous Australians make up 2.5 per cent of Australia's population but they account for 26 per cent of the nation's jail population.

Between 2000 and 2010, the indigenous imprisonment rate increased by 51.5 per cent; at the same time, the non-indigenous rate increased 3.1 per cent.

In 1991, Aborigines represented one in seven people in Australian prisons. Currently, they account for one in four prisoners.

Aboriginal juveniles are 31 times more likely to be in detention than non-indigenous juveniles.

The imprisonment rate for indigenous females increased 58.6 per cent between 2000 and 2010.